- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cyclone season

- Article Subtitle: The toll of cruelty and ignorance

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

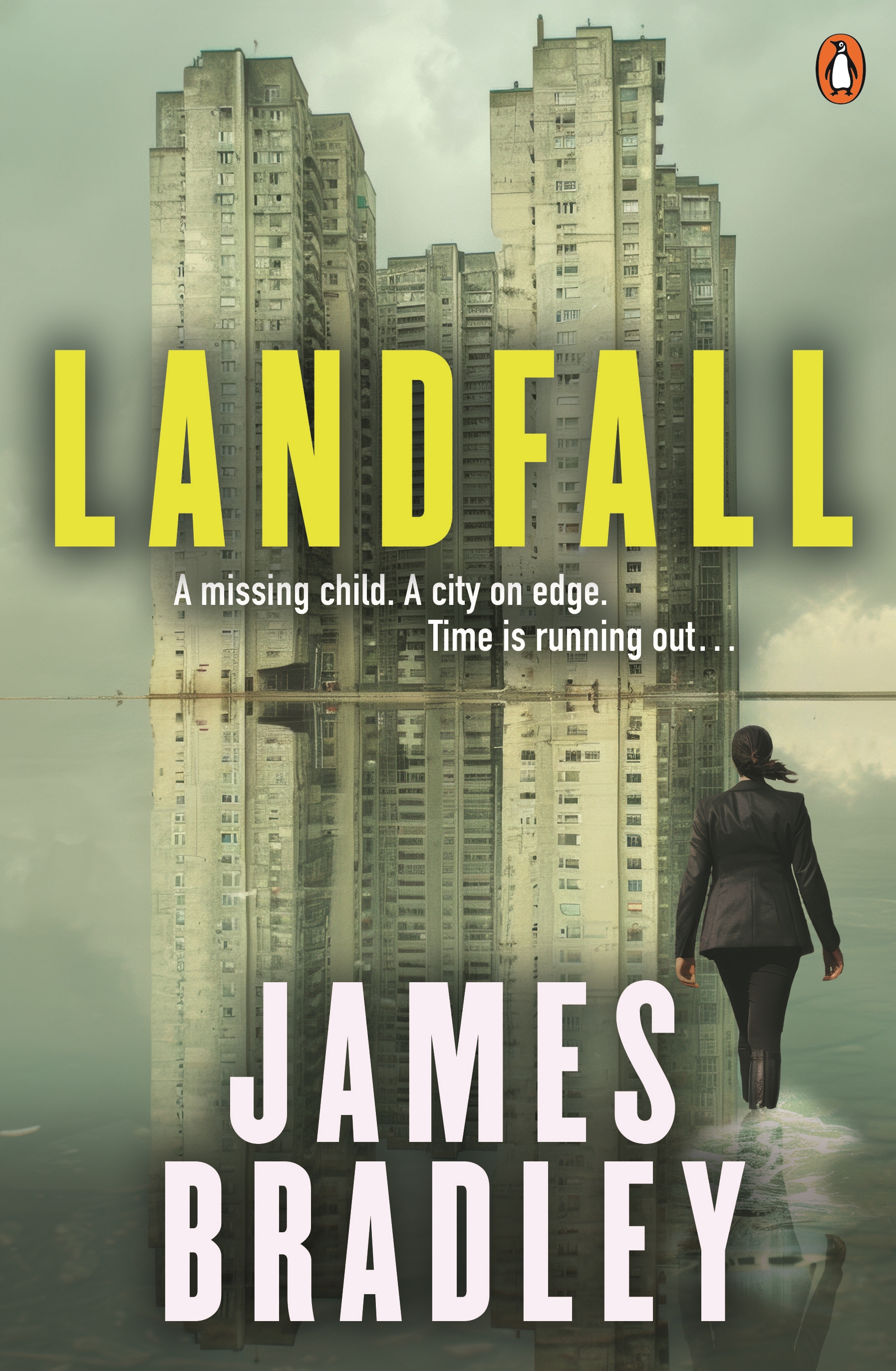

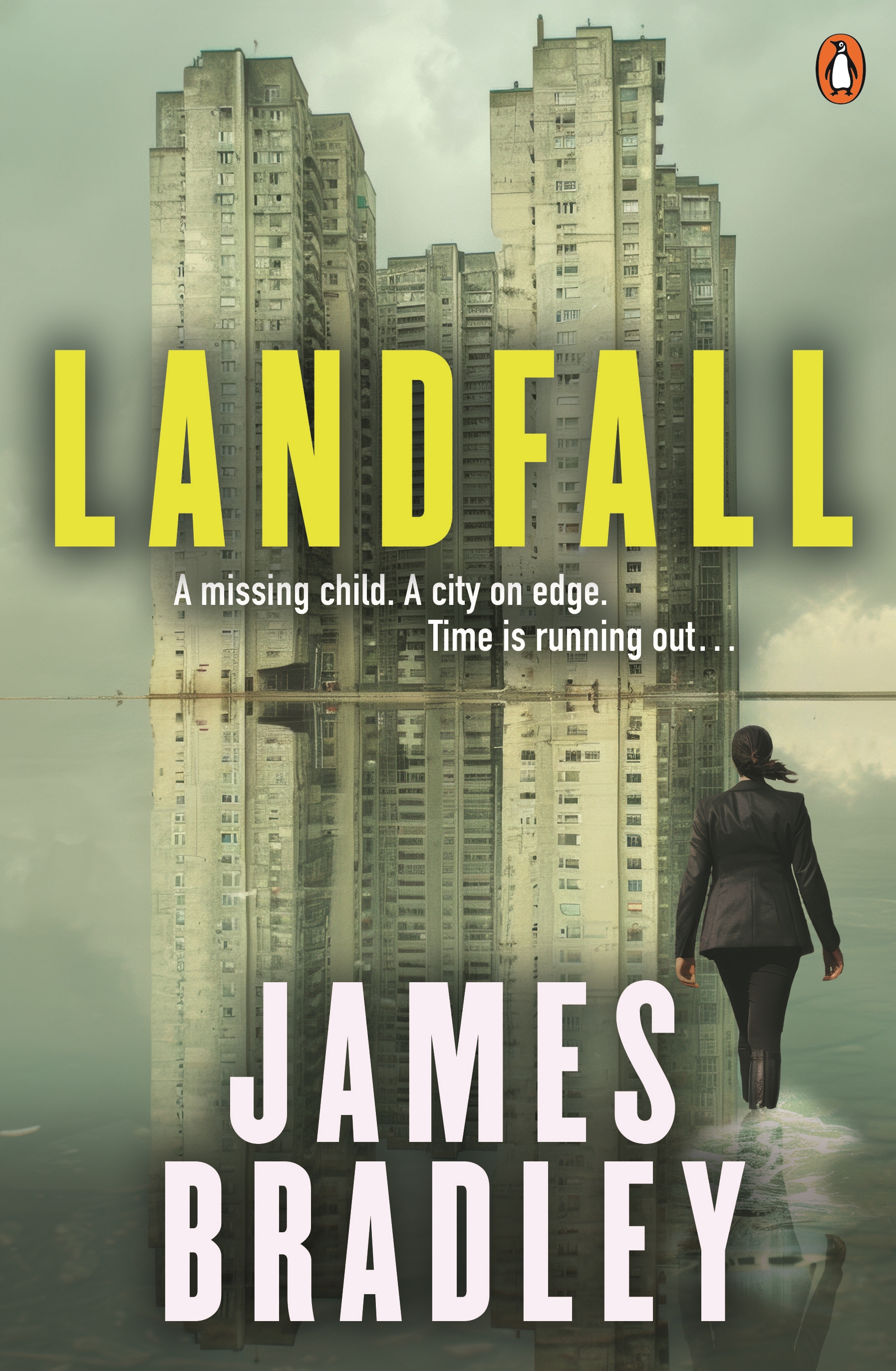

Defined meteorologically, landfall refers to a storm which strikes land after forming over water. By another definition, it is the first sight of a traveller who, like the aforementioned storm, has spent too long at sea. Both are destination and terminus, so it is unsurprising that the writer who edited The Penguin Book of the Ocean (2010) would pen a novel obsessed with water, and with people crossing it, sheltering from it, or simply trying to stay afloat. The inhabitants of Landfall are already deluged, and another storm is on the way. Beginning on a Monday morning and with a tropical cyclone due by week’s end, time in the novel is running short from the very start.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Adam Rivett reviews ‘Landfall’ by James Bradley

- Book 1 Title: Landfall

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $34.99 pb, 317 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761349881/landfall--james-bradley--2025--9781761349881#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

The clock ticks also for Casey Mitchell, a five-year-old girl gone missing from a Sydney residential area known as the Floodline. The setting is an Australia of the near future, already reeling from one climate disaster caused by Antarctic meltwater and bracing for future catastrophes. Tasked with navigating this aqueous terrain and finding Casey is Senior Detective Sadiya Azad and her offsider, Detective Sergeant Paul Findlay. But it isn’t only the landscape which bears the marks of trauma: the mood and morality of the country has grown waterlogged, leading to a comparable state of collapse. Landfall is climate fiction of an Australia still to come, but it is also one that is very much about our present moment, and our harrowing, frequently unaddressed past.

While the police’s investigation into Casey’s disappointment is the novel’s central thread, its other narrative strand concerns Tasim Benakat, an Indonesian refugee who arrived in the country by boat and whose fate becomes, over the course of the week, inexorably tied to Casey’s. Like the novel’s imminent cyclone, he is a figure defined by a journey made across water. His story starkly addresses Australia’s cruel and dehumanising treatment of refugees, but also skilfully ties historical wounds to future calamity; in the world of Landfall, individual suffering becomes communal – all struggle against the rising tide.

Bradley’s concern for the fragile and the vulnerable, and how that humanity infuses the novel’s procedural aspects, is Landfall’s greatest achievement. It is a hybrid detective sci-fi novel, but the genre splicing and high-tech patina always feel in service of an empathetic vision. What the novel reveals, over the course of three hundred pages, is a toll of cruelty and ignorance, a toll from which no one is spared. Tasim’s hunt for Casey, and the backstory of his punitive treatment, connects with Bradley’s other persistent concern: children.

Climate change is often framed in terms of legacy and the world we will leave for future generations, and Landfall deftly connects each character’s past to the country’s faltering future. As the hunt for Casey and Tasim’s memories sharpen into focus in the novel’s second half, so too does a portrait of Sadiya’s increasingly frail and demented father, Arman, whose own story is one of exile and impermanence. ‘Too many kids have been grabbed and trafficked’ says Jay, Casey’s father, during his first conversation with Sadiya. Those who have wandered into the internet’s darker or more conspiracy-laden corners will immediately recognise the febrile online right-wing language. The paranoid concerns of many of the novel’s characters are wholly in step with the often extreme (but also increasingly mainstream) talking points of our current moment. It isn’t only child trafficking – Landfall touches upon surveillance, AI, crop failures, white nationalism, and corporate interference in democracy. It is a testament to Bradley’s skill that the contemporary echoes mesh with the world-building necessities of climate fiction, and that he never loses track of either the characters or the novel’s propulsive narrative. All blend and eddy, each component affecting and defining the other.

Unfortunately, the novel’s clumsiness often negates these successes, with Bradley often lapsing into clichéd language and structures. Characters ‘wake with a start’. As Sadiya steps out of her car, the heat ‘hits her like a wall’. The interrogations, typical of the genre, are similarly sandbagged by formulaic language (‘I don’t have time for this shit’, ‘I can promise you, your life won’t be worth living’). Its structure can likewise feel episodic, with scenes often topped and tailed too conventionally, beginning with a detective’s car pulling up and ending with a new clue and a final statement (‘Good idea’, ‘Bingo’, ‘We need to get over there right away’). A detective novel and a mystery necessarily balance formula against inspiration, but when compared to the stronger lyrical and descriptive writing found elsewhere in the book, these devices drag down the novel.

I read Landfall during our election campaign, a month-long rhetorical desert in which the media and politicians spent countless days discussing a fuel-excise tax rebate countable in loose change, while brushing over potential future crises as quickly as possible. Our own imminent cyclone approaches and we are grimly committed to ignoring it, via either tokenistic lip service or outright denialism. It is possible our imagination falters before such potential annihilation, and it is undeniable many people in this country are well rewarded by keeping the electorate distracted and cynical. There is no doubting that staring down our future for any length of time is a terrifying proposition.

While not wholly successful, Landfall is nonetheless a compelling work and a convincing portrait of a world to come. The best of it lingers.

Comments powered by CComment