- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lurid lives

- Article Subtitle: Medieval women mystics

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When teaching the history of medieval Europe it is hard to resist regaling students with lurid accounts of some of the extreme devotional practices performed by medieval women mystics. Saint Catherine of Siena, so it was claimed, drank the vomit of lepers to abase herself before God. Marie of Oignies, apparently, refused to eat anything but the consecrated host and died of starvation. Julian of Norwich lived in seclusion, inside a cell attached to a church, having renounced all things of the world including the opportunity to go outside. These women’s lives, in the retelling, can offer a visceral sense of the strangeness of medieval religious culture, and can also provide a sense of the particularity of gendered celebrity in pre-modernity. As a teacher, however, I am loathe to lean too heavily into the ostensible spiritual otherness of the Middle Ages. I worry that presenting these women as freaks risks alienating students from the historical work I am training them to do; to make sense of historical difference on its own terms.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Clare Monagle reviews ‘Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife: The extraordinary lives of medieval women’ by Hetta Howes

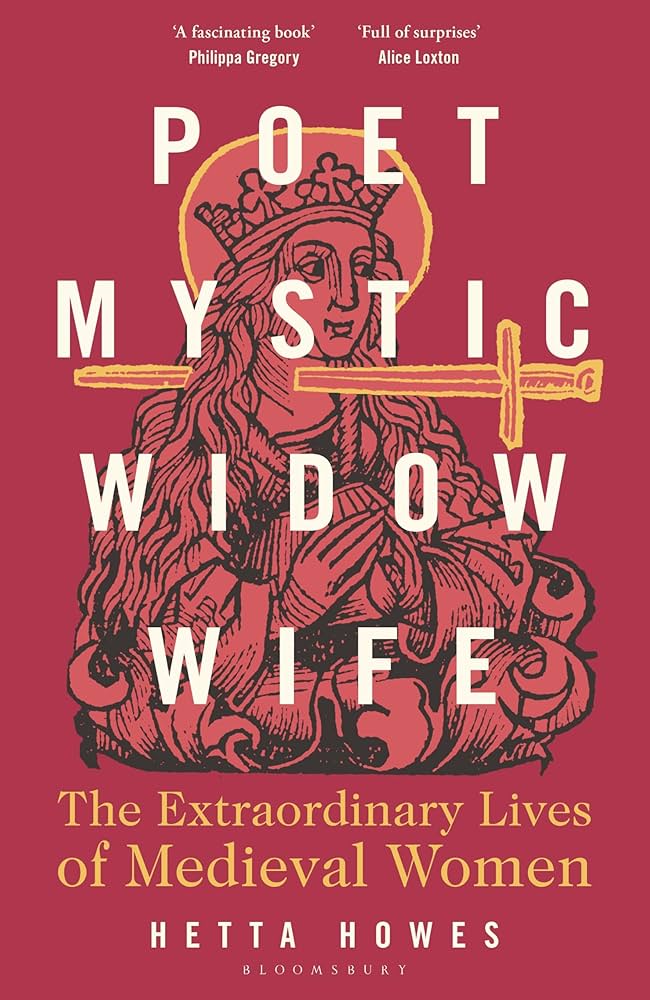

- Book 1 Title: Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife

- Book 1 Subtitle: The extraordinary lives of medieval women

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $34.99 pb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781399420082/poet-mystic-widow-wife-the-extraordinary-lives-of-medieval-women--hetta-howes--2024--9781399420082#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

In Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife, Hetta Howes explores the lives of four eminent medieval women to open a window on practices and hierarchies of gender in the Middle Ages. Writing accessibly for a general audience, Howes works hard to resist the temptation of exoticising these medieval women and takes care to rationalise their choices within the rules that governed their world and the beliefs that structured their reality. Howes’s cohort consists of the courtly poet Marie de France, the aforementioned Julian of Norwich, the late-medieval writer Christine de Pizan, and the ever-weeping married mystic Margery Kempe. These women are notable, not only because they obtained significant fame in their own time, but because their writings convey a sense of personality and vivacity that seems to shorten the historical distance between them and us. The same cannot be said for a great many medieval writers. (I’m looking at you, Thomas Aquinas.)

Howes’s method still runs some risk, in spite of her careful placement of these women in their historical context. One risk is that because her sample consists of women who are so anomalous, it cannot be said to represent medieval women at large. Literacy was very limited in the Middle Ages and was almost exclusively the province of the clergy, merchants, and high-ranking officials. Women’s literacy was, unsurprisingly, even more limited. After all, women were barred from universities, and thus denied participation in the institution that trained most of those clergy and administrators in the advanced writing skills their work demanded. Women such as Marie de France and Christine de Pizan were able to become writers as members of affluent noble, or noble-adjacent, families, a status which gave them access to private tutors. Religious celebrities such as Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe collaborated with male confessors, clergy to whom they confessed and from whom they sought spiritual counsel. Together, they composed the women’s work. Female mystics gained literary purchase by spiritual reputation. Their fame attracted the attention of priests who, perhaps seeking to burnish their own status, worked with the women to record their visionary and prophetic utterances. A lot of things had to go right for a medieval woman to become an author, and most of those things were unavailable to most women. So what, if anything, can Marie, Christine, Julian, and Margery tell us about the lives of women in the Middle Ages?

Howes’s answer is to describe the conditions that enabled these exceptional literary lives; to offer an illuminating contrast with the limitations that applied to the lives of ordinary women. She draws on a rich range of sources to flesh out the accounts of her women writers, and to cross check their accounts against what we know about medieval society. Howes wears this reading and learning lightly. The reader is never bogged down in historiographical quibbles or lost in scholarly posturing. The book provides a clear and compelling introduction to the history of medieval women, neither intimidating nor patronising the reader.

Does it make me a hypocrite, then, to say that I missed the weirdness of these women as I have come to know them as a reader? The words of Margery Kempe, for example, convey the thrill of a world in which demons tempt and the Holy Spirit protects. Marie de France gives us the ascetic erotics of courtly love, in which desire is not to be overcome through consummation but enjoyed as deprivation. Julian of Norwich provides the gnomic affirmation, ‘And all shall be well. And all shall be well. And all manner of things shall be exceedingly well.’ Christine de Pizan imagines an allegorical ‘City of Ladies’, an urban paradise peopled by brilliant historical women. In making these authors accessible to us, legible in their time and place, Howes deprives us of their idiosyncratic authorial power and dilutes the potency of their personality. Poet, Mystic, Widow, Wife provides a useful and thoughtful introduction to the lives of medieval women, no doubt. But I do hope that its readers take it as a first step into a sprawling city of medieval ladies, as Christine de Pizan might have had it.

Comments powered by CComment