- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: ‘Rejecting the system it created’: How Trump’s America is reshaping Australia’s regional relations

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: ‘Rejecting the system it created’

- Article Subtitle: How Trump’s America is reshaping Australia’s regional relations

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For Australia, a nation that has long balanced its economic ties to Asia with its security alliance with the United States, the second Trump administration represents an unprecedented challenge to its foreign policy. The return of Donald Trump to the White House has ushered in a new era of economic nationalism that threatens to reshape the Asian security landscape. For the newly re-elected Albanese Labor government, this presents plenty of risks. But its decisive mandate also provides an opportunity for Australia to develop greater self-reliance in foreign policy and deepen relationships across Asia.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): ‘“Rejecting the system it created”: How Trump’s America is reshaping Australia’s regional relations’ by Rebecca Strating

The cornerstone of Trump’s second-term foreign policy has been his ‘reciprocal’ tariffs, announced in April as a ‘declaration of economic independence’ on what he called ‘liberation day’. This economic offensive has hit East Asian nations particularly hard. While China faced a punishing 145 per cent tariff before it struck a deal with the United States in May, even traditional US partners like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have been characterised as economic rivals and allotted significant tariffs. Southeast Asian nations find themselves caught in the crossfire with Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam facing tariffs of forty-nine, forty-eight, and forty-six per cent respectively. By comparison, Australia has been treated relatively leniently with a baseline tariff of ten per cent.

Just hours after the reciprocal tariffs went into effect on April 9, Trump announced a ninety-day tariff freeze and triggered a rush of bilateral negotiations. Vietnam, for whom the United States is its largest market, generating around thirty per cent of its GDP, faces a stark economic future if the tariff rate goes ahead. Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh described it as a ‘challenging and complicated situation’ as Vietnam scrambles to negotiate terms, reportedly offering to crack down on Chinese goods transhipped through its territory and to reduce tariffs on American products.

Indonesia, facing a thirty-two per cent tariff imposed by the United States, its second largest export market (after only China), has also dispatched negotiators to Washington. For newly elected President Prabowo Subianto, reducing these tariffs represents an early leadership test as he attempts to maintain Indonesia’s ‘free and open’ foreign policy through his ‘zero enemies, one thousand friends’ approach.

Most Southeast Asian nations have so far opted for hedging strategies that maintain relationships with multiple partners. There is concern that the United States will try and force smaller countries to choose between it and China. As Malaysia’s trade minister Tengku Zafrul Aziz declared, ‘We can’t choose and we will never choose’ between great powers. Singapore’s Prime Minister Lawrence Wong was more blunt, criticising the United States for ‘rejecting the very system it created’.

The longer-term trend in Southeast Asia is towards reduced economic reliance on both the United States and China while strengthening intraregional ties and partnerships with other external actors, including Australia. These nations are working within the framework of ASEAN, the ten-member association established by Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Singapore in 1967, to pool their power and make the Southeast Asian region more attractive and competitive. But most Southeast Asian countries will also continue to build relations with other friends that are less friendly to Australia’s interests, such as Russia, including through groupings such as the BRICS organisation (originally Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa), which has sought to challenge US economic dominance.

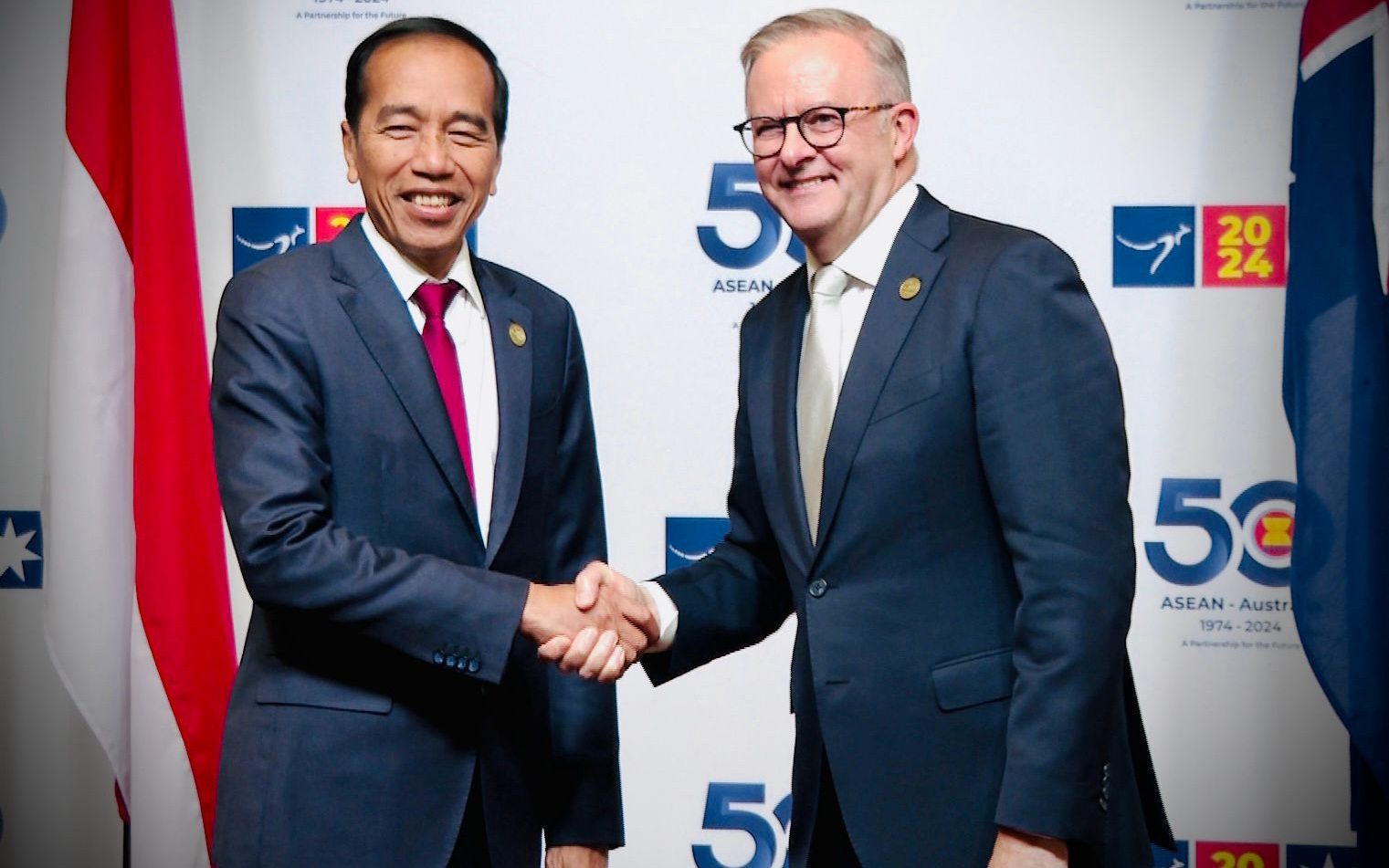

President Joko Widodo and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at the 2024 ASEAN-Australia Special Summit (Secretariat of the President of the Republic of Indonesia via Wikimedia Commons)

President Joko Widodo and Prime Minister Anthony Albanese at the 2024 ASEAN-Australia Special Summit (Secretariat of the President of the Republic of Indonesia via Wikimedia Commons)

Beijing is actively seeking to capitalise on the reputational costs of US tariffs. President Xi Jinping’s diplomatic visits to Vietnam, Malaysia, and Cambodia in April gained additional significance against the backdrop of Trump’s tariffs, significance exacerbated by Trump’s characterisation of these visits as an attempt to ‘screw’ the United States. Xi’s core message that there are ‘no winners in a tariff war’ attempts to frame China as the responsible economic actor. However, it will not be so easy for China to simply fill the soft power vacuum left in Southeast Asia by Trump’s policies, including its cuts to USAID. Most Southeast Asian countries also harbour distrust towards Beijing and compete economically with Chinese industries, fearing that Chinese products will flood local markets. Indonesia and Vietnam, for instance, have imposed anti-dumping tariffs to protect their markets from cheap imports.

The Philippines presents an interesting counterpoint to the regional hedging trend. During my visit to the Manila Dialogue on the South China Sea – coincidentally on the day Trump was elected – I witnessed firsthand the lack of concern around potential changes in US policy. Instead, analysts remained focused on what they saw as the bigger challenge: China’s maritime assertions in the West Philippine Sea. As a committed US ally under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, the son of former President Ferdinand Marcos (1965-1986), the Philippines continues to rely on American security guarantees. US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s visit to Manila in March, during which he confirmed America’s ‘ironclad’ commitment to their Mutual Defense Treaty, reinforced this alliance. Notably, the United States has exempted defence assistance to the Philippines from its global foreign aid freeze.

Japan also moved quickly to secure commitments from the Trump administration. After Trump’s summit with Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba – notably the second bilateral meeting of Trump’s presidency – the United States affirmed Japan’s position as America’s ‘indispensable partner’ in deterring Chinese aggression. During Trump’s first term, then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe cultivated what some described as a ‘bromance’ with Trump, leveraging their shared interest in golf to secure important commitments. Whether Ishiba can build similar rapport remains uncertain.

Asia currently faces disparate potential futures. First, Trump’s economic confrontation and demands for allies to pay more for protection create broader uncertainty about American credibility, particularly for Japan and South Korea, where tens of thousands of American troops are stationed. This raises the prospect that Asian countries will seek new alliances, including with China, or increase defence spending to become more self-reliant.

Second, Trump’s suggestion that he would be ‘very nice’ to China if negotiations commenced raises the unlikely possibility of a grand bargain between Washington and Beijing. Trump’s approach to Ukraine’s negotiations with Russia – effectively conceding occupied territories – offers little reassurance that any economic deal with China wouldn’t include reduced American presence in East Asia. This would be disastrous for those US allies – particularly Australia – that have bet big on the United States remaining in Asia to counterbalance China’s rise.

Third, there remains the possibility of a future where conflict rather than cooperation wins the day, with Taiwan as the most concerning flashpoint. While the Taiwanese public largely continues normal life despite threats from across the Taiwan Strait, recently there has been significant interest in a futuristic TV series called Zero Day, which envisions a People’s Liberation Army invasion scenario.

Taiwan faces daily pressure from China’s ‘Anaconda Strategy’ – aircraft and naval vessel actions designed to squeeze Taiwan – as it prepares for a potential ‘D-Day’ invasion. On both fronts, it relies heavily on US support. The Trump administration’s reversion to strategic ambiguity regarding Taiwan’s defence has placed pressure on Taiwan’s leadership to negotiate new arrangements with the United States, including by announcing a promise to boost Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s investment in US chip manufacturing by $100 billion.

Another concerning development is talk of nuclear proliferation in East Asia. During several visits to South Korea over the past year, I have observed increasingly serious discussion about whether the nation should develop nuclear weapons. Trump’s unprecedented recognition of North Korea as a nuclear power has already prompted South Korean Foreign Minister Cho Tae-Yul to publicly suggest nuclear weapons remain an option for Seoul.

Seoul’s security concerns are understandable. In 2018, Trump became the first sitting US president to meet with a North Korean leader when he held a summit with Kim Jong Un in Singapore. Though he failed to reach a deal with Kim, it is hard to forget the infamous twenty-seven ‘love letters’, as they became known in the press, exchanged between the leaders.

On the ground in Korea you cannot fail to appreciate its proximity to North Korea. Seoul lies just 35 kilometres from the Demilitarised Zone. North Korea’s recent mutual defence treaty with Russia, signed in June 2024, only compounds these concerns. In this environment, South Korea’s consideration of domestic nuclear weapons seems rational, with public opinion increasingly favouring nuclear arms over reliance on American security guarantees. Japan, with its nuclear technology, infrastructure, and knowledge, is widely assumed to be ‘a screwdriver’s turn’ away from developing the bomb. Regional powers like China and Russia would likely respond negatively to Japanese or Korean nuclearisation, potentially triggering an arms race that would severely undermine Australia’s security interests and regional stability.

For Australia, these developments pose profound questions. During Trump’s first administration, Australia ultimately deepened its alliance with the United States despite initial tensions. The AUKUS agreement, signed during Biden’s presidency by then Prime Minister Scott Morrison, further cemented Australia’s alignment with the United States against China. This time, however, Australia cannot assume American policy will ‘normalise’. Trump’s re-election is a consequence of enduring structural changes in America’s economy, society, and political culture. While Canberra should not abandon its American alliance, it should be guided by Australia’s national interests, rather than by values or sentimental attachment to American exceptionalism.

As the United States retreats from development, information, diplomacy, and international education programs, the Albanese government must improve its capacity to collaborate with partners in Asia. This approach requires greater investment not just in defence but in all forms of statecraft. Australia need not become China’s close partner but it must maintain a stable relationship with the great power. The choice of Indonesia as Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s first post-election visit signals the Labor government’s commitment to strengthening ties in Southeast Asia. In contrast, during the election campaign Opposition Leader Peter Dutton committed to visiting Washington first, reflecting a difference in the priorities of the two major parties.

But engaging more with the region will require both pragmatism and creative diplomacy. Australia needs to hold firm to its own democratic values while working within a world that is becoming safer for authoritarianism.

A potential new nuclear arms race in Asia would create profound challenges for Australia’s foreign policy. Australia has benefited from the American nuclear umbrella while championing non-proliferation norms through the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which Australia ratified in 1973. Regional scepticism towards nuclear weapons partly explains concern from Indonesia and Malaysia about Australia’s nuclear-powered submarines under AUKUS, which they fear might accelerate regional arms competition. The Albanese government has worked to reassure neighbours that AUKUS does not represent a pathway to nuclear weapons, lessening anxieties in some but not all of Australia’s regional neighbours.

Regional and extra-regional partners will need to adapt or form new coalitions that function without American leadership. The groundwork exists. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, signed in 2018 after the first Trump administration withdrew the United States from the original Trans-Pacific Partnership, could encompass nearly a third of global import markets if expanded to include the European Union and other countries such as Korea. While multipolar systems have historically been considered less stable, Matthew Sussex of the Centre for Defence Research at the Australian Defence College observes that they can ‘allow middle powers to thrive’ – if they are nimble enough to adapt.

This means developing greater self-reliance within the alliance framework and hedging against dependence on the United States through deepening partnerships across Asia. Australia must invest in its diplomatic capacity to navigate an increasingly complex regional environment where American leadership can no longer be taken for granted and where China’s influence continues to grow. For Australia, the coming years will require unprecedented diplomatic agility. The future of East Asia will be shaped not just by great power competition between America and China, but by how middle powers respond to this new reality. Australia’s challenge is to maintain its core strategic relationships while expanding its diplomatic and economic options. The first step is recognising that the old certainties no longer exist.

This article is one of a series supported by Peter McMullin AM via the Good Business Foundation.

Comments powered by CComment