- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The deepest cut

- Article Subtitle: Democracy in the Middle East

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Fawaz Gerges is a leading expert on mainstream Islamist movements, jihadist groups, and social movements in the Middle East. He has interviewed hundreds of civil society leaders, activists, and mainstream and radical Islamists in the Muslim world and within Muslim communities in Europe. Two decades ago, his in-depth field research resulted in The Far Enemy: Why Jihad went global (2005). It showed that the 9/11 terror attacks united social forces in the Muslim world against Al Qaeda. The dominant response of jihadi groups was an explicit rejection of Al Qaeda and total opposition to the internationalisation of jihad. The US invasion of Iraq in 2003 and its subsequent occupation gave Al Qaeda a ‘new lease on life, a second generation of recruits and fighters, and a powerful outlet to expand its ideological outreach activities to Muslims worldwide’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Clinton Fernandes reviews ‘The Great Betrayal: The struggle for freedom and democracy in the Middle East’ by Fawaz A. Gerges

- Book 1 Title: The Great Betrayal

- Book 1 Subtitle: The struggle for freedom and democracy in the Middle East

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press, $59.99 hb, 384 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780691176635/the-great-betrayal--fawaz-a-gerges--2025--9780691176635#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Gerges brings this deep knowledge of the region to his new book, The Great Betrayal: The struggle for freedom and democracy in the Middle East. In contrast to many works that focus on the actions of rulers and élites, Gerges integrates the experiences of ordinary people into his analytical framework. He shows how a combination of domestic authoritarianism and foreign intervention excludes the people of the Middle East from democratic representation and effective government. The ‘betrayal’ in the title refers to the difference between what was promised – national self-determination – and what was delivered.

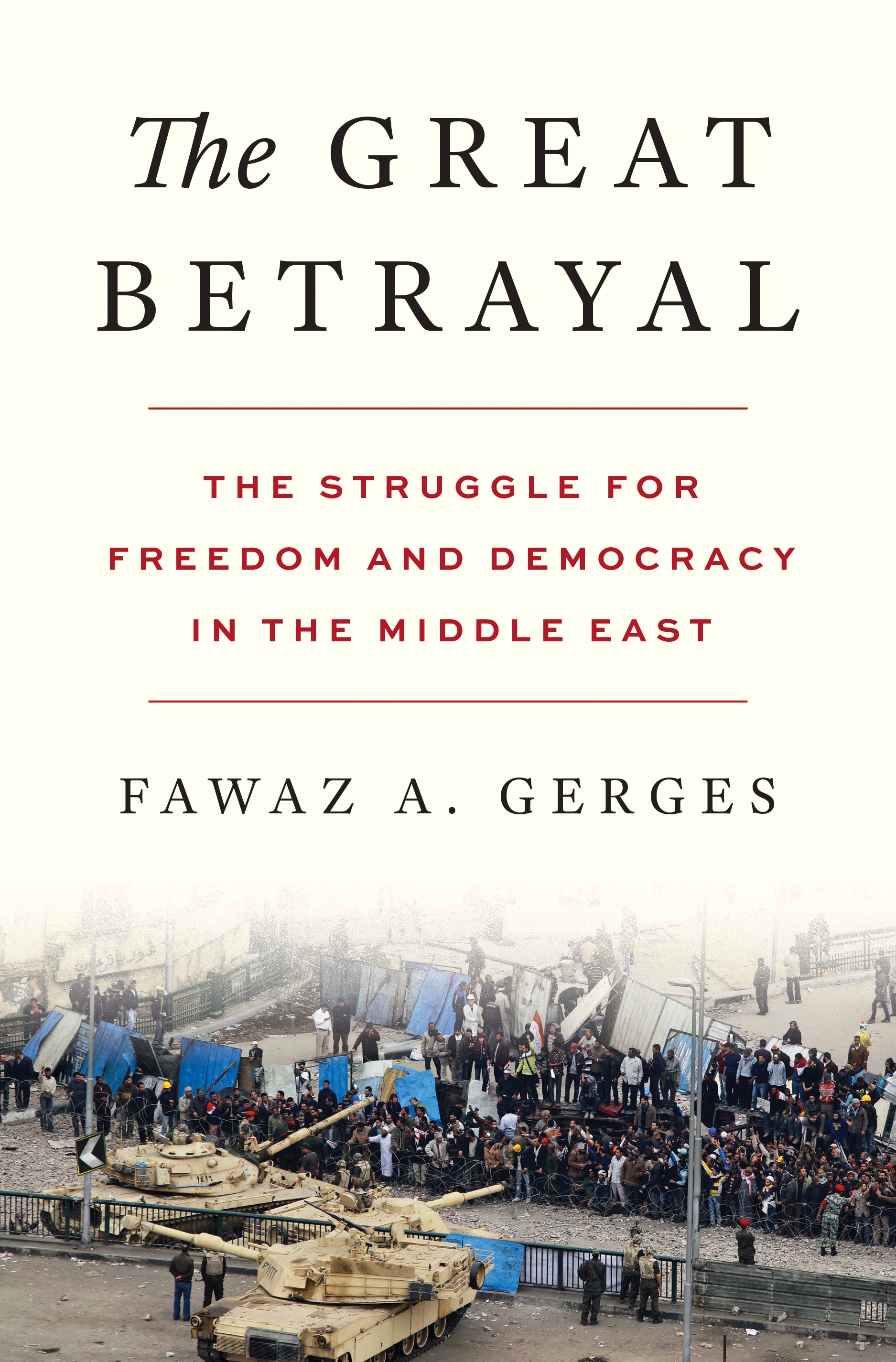

Protest in Tahrir Square, Cairo, 2011 (George Henton/Alamy)

Protest in Tahrir Square, Cairo, 2011 (George Henton/Alamy)

Gerges begins with the machinations of Britain and France during World War I. His central characters will be familiar to many readers – the Emir of Mecca, Sharif Husayn Ibn Ali, and his 1915-16 correspondence with the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Sir Henry McMahon. These letters involved British support of an independent Arab state and Arab assistance to Britain in opposing the Ottoman Empire. Such discussions were undermined by the secret convention between Britain and France in May 1916, known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement, and Britain’s Balfour Declaration of 1917. Gerges retells this story briefly, calling the Balfour Declaration the ‘deepest cut of all’.

The words ‘Zionism’ and ‘Christian Zionism’ do not appear in the index. A consideration of the latter would have allowed Gerges to expand on his discussion of foreign intervention. This began decades before Theodor Herzl’s influential 1896 pamphlet, The Jewish State; English evangelicals such as Anthony Ashley-Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-85), advocated the establishment of a Jewish polity in Palestine. Nineteenth-century English Protestantism was heavily informed by the concept of dispensationalism, which believed that returning the Jewish people to Palestine was a prophetic requirement for the Second Coming of Jesus. In the United States today, people who fit into the category of ‘white evangelical Protestant’ often have similar views. They form about thirteen per cent of the US population – more than forty-seven million people – but make up one-third of the Republican Party’s voting base.

Gerges expertly outlines the failures of the liberal constitutional order in Egypt in the interwar years. He shows how the ‘corrupt and unscrupulous personalities within [the ruling party’s] ranks’ caused ordinary people to become disillusioned. Domestic repression followed, and when this wasn’t enough to quell opposition, it was assisted by the imperial forces of France and Britain. Gerges goes on to show how similar patterns of behaviour were repeated across the Arab world, as domestic repression worked alongside foreign intervention to preserve an authoritarian political order. He takes us through life in the newly independent countries after World War II and decolonisation. The ambitious United Arab Republic, a political union of Egypt and Syria in 1958, proved unworkable, collapsing three years later, and we are given a valuable summary of the socio-economic reasons for the breakdown of this political marriage of two very unequal economic partners.

Gerges then examines the Middle East during the Cold War, providing useful snapshots of important events during this time. His analytical framework helps him tell his story well – domestic authoritarianism and foreign intervention work together to thwart popular aspirations. He extends this discussion into more recent events, such as the Arab Spring revolts (2010-12 and 2018-19).

America’s interest in the region’s oil and gas riches is part of his narrative. However, it should be noted that US policy is not motivated by the need to gain access to oil. ‘Access’ implies that the United States simply wishes to buy oil like any other country, at a reasonable price. In fact, America has obtained its oil from domestic sources and Latin American suppliers for more than a century. It has also exported some crude oil for more than a century. Today, US shale oil production has made it the world’s biggest producer of oil, with a twenty-two per cent share of global production. (Saudi Arabia is a distant second with eleven per cent.) The United States wants control, not access. The distinction is crucial. Control of oil means controlling the terms on which other countries can access their oil. As an example, US policy planners wanted to exercise what they called ‘veto power’ over Japan’s economy after World War II by controlling its overseas sources of energy supply. The policy isn’t always about cheap oil, either. When needed, the United States has asked its Arab protectorates to reduce supply and increase the price of oil, for example when it wanted to improve its relationship with Iran in 1986.

Control also refers to how the oil-rich regimes spend their revenues. The Arab monarchies pay tribute by buying huge investment portfolios in US Treasury securities, banks, and corporations. They ensure that some of the dollars they earn from oil sales will flow back to US corporations. The monarchies use their oil profits to buy advanced US weapons systems. This recycling of oil revenues ensures a huge foreign subsidy for high-tech US industry. Saudi Arabia, for instance, had a stockpile of around US$140 billion in US Treasury holdings in 2024. Kuwait, another family dictatorship, had a stockpile of more than US$45 billion. The United Arab Emirates is a major buyer of advanced US weapons systems. Qatar hosts the forward headquarters of US Central Command at Al Udeid Air Base, which it built at a cost of more than US$1 billion. Its sovereign wealth fund has committed more than US$45 billion to investments in US corporations. Qatar Airways is a major buyer of US commercial aircraft. Again, it’s about control, not access.

Although Gerges is realistic about the severe challenges facing the region, his analysis also shows that its people cannot be counted out. The Middle East and North Africa have the largest youth cohorts in the world, with sixty per cent of the population in these regions under the age of thirty. These two regions also share the highest youth unemployment rates in the world. The authoritarian stability that prevails for now may yet be overthrown. Gerges’s study will be a useful companion to observers in the years ahead.

Comments powered by CComment