- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Method and message

- Article Subtitle: Rethinking Australian military history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Readers of Stephen Gapps’s work will be delighted to see this latest instalment of his quest to highlight the reality of Australia’s internal wars from 1788. Gapps’s first major contribution to this literature was The Sydney Wars (2018), which detailed the military conflicts between the Darug-speaking peoples of Sydney Harbour and the British newcomers from the First Fleet to 1817. His second, Gudyarra (2021), focused on the battles between the Wiradyuri and the settlers around today’s Bathurst region from 1822 to 1824. Gapps’s new book, Uprising, takes us over the full middle swathe of colonial New South Wales, including campaigns from dozens of clans, between 1838 and 1844. Each volume moves us forward in time and over greater expanses of Country. Collectively, the Gapps trilogy is a clear and detailed refutation of Australia’s continued reluctance to name the violent episodes that occurred between black and white peoples before 1901 as what they so plainly were: war.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kate Fullagar reviews ‘Uprising: War in the colony of New South Wales, 1838-1844’ by Stephen Gapps

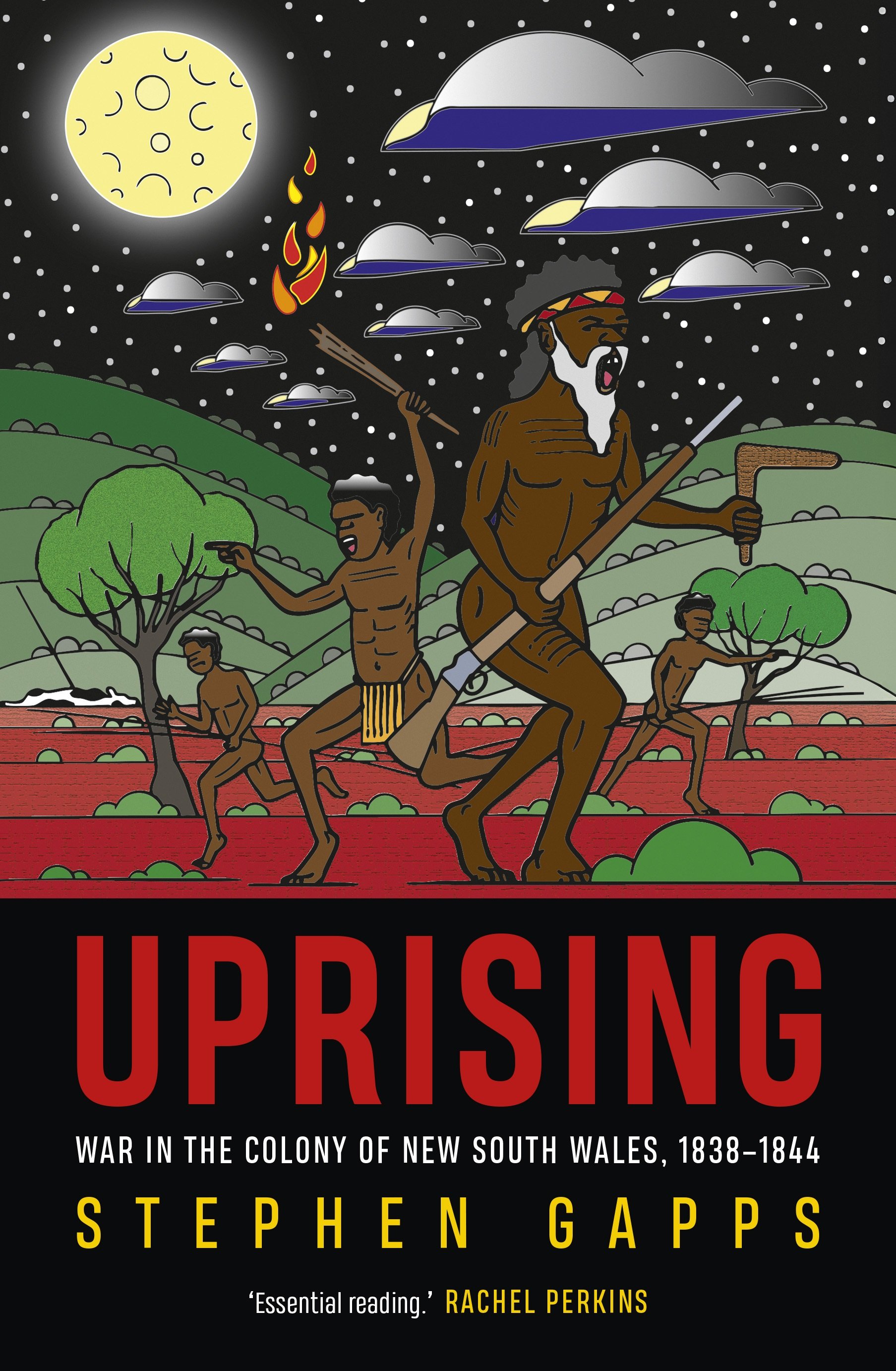

- Book 1 Title: Uprising

- Book 1 Subtitle: War in the colony of New South Wales, 1838-1844

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $36.99 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781742238029/the-rising--stephen-gapps--2025--9781742238029#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Not that Gapps refers to his work as a trilogy; he may plan to carry on with his instalments until he reaches both the west coast and the twentieth century. If he manages to include the same level of detail he does in Uprising, future volumes will only get fatter. Detail is the hallmark of Gapps’s work. It’s not just a personal tic; it is the method and the message. The overloading of examples, the endless white excuses and black countermoves, the refusal to ever give the reader a break from the cascade of violence: all this works to build a store of evidence to deploy against tired appeals to Aboriginal disorganisation or noble frontiersmen.

Uprising opens with a narration of the 1838 ‘Faithfull Massacre’ near today’s Benalla, where eight stockmen, on their way to settle land near Port Phillip, were killed by ‘a large force of warriors’. The event became ‘etched in local memory’ as a senseless attack on defenceless whites. In the context of what came before and what followed, it should rather be seen as ‘one of the great Aboriginal military victories in the entire Australian Wars’. It served as the opening battle of ‘arguably the greatest military counteroffensive on Australian soil’.

Counteroffensive is the operative word here. Gapps is careful throughout the book to point to the ways that every so-called massacre of whites was always a retaliation for settler damage to Aboriginal life and Country. In this way, ‘massacre’ starts to look like a weak label. Battle seems more appropriate. And with enough battles in interconnected lands within a relatively short span of time, the notion of war – fought defensively – emerges as the most logical term.

Ten chapters follow with example after example, from Gameroi raids in the Northern Tablelands, to Wiradyuri defences of the Murrumbidgee, to mixed-clan attacks on settlers in the Lockyer Valley. Gapps’s erudition is astounding. He has scoured newspapers, journals, court records, and elders’ memories to recreate scores of instances that, when lined up together, point to a motivated, coordinated, and justifiable military campaign on the part of Aboriginal warriors over six years.

Occasionally, the erudition can feel relentless. In style, Uprising resembles a book that it cites often and favourably. Bill Gammage’s The Biggest Estate on Earth (2012) made a similarly grand, revisionist point about the land-managing practices of Aboriginal Australians by piling on example after example. Given the success of The Biggest Estate on Earth this perhaps augurs well for Uprising. But some kind of arc to the campaign may have helped readers. European military history is a perennially popular genre, but the best of these works usually trace a dynamic path, or one especially revealing character, even one exemplary battle. There are few stand-out personalities or developing movements in Gapps’s work: the extraordinary sameness, in fact, is one of its key points.

One way that Gapps might have textured the sameness without diminishing its salience would have been to reflect on some global comparisons. An event that occurred to me frequently while reading Uprising was the pan-Indian war that spread across colonial North America in 1765-66. Too often dismissed by the label Pontiac’s Rebellion, this war was in truth a prolonged, unexpected, and extremely damaging counteroffensive by a huge variety of Native American groups against multiple colonies. Gapps would surely empathise with the few historians who have tried to argue that this cluster of battles was in fact the first American War of Independence. The comparison stuck with me because one of the biggest questions concerning the 1760s war in North America is how rival clans managed to overcome their long-standing differences. It made me ask the same question of Gapps’s exemplary clans, which surely harboured some ancient enmities, as all clans do. How coordination occurred is less important in Gapps’s book than the fact that it existed at all.

Another international parallel is what was happening in Europe at roughly the same time as the Aboriginal uprising. The 1830s and 1840s saw scores of class-based and ideologically driven riots across the continent, culminating in a wave of actual revolution in 1848. Britain has always stood out in this history for being one of the few places that managed to forestall a full-blown revolution. Gapps’s book makes me wonder if in fact Britain did experience wholesale insurgency in this tumultuous age – not within the British Isles but halfway round the world, in its fledgling New South Wales colony.

Such musings on the Australian War of this era are less a criticism of Gapps’s Uprising and more a tribute to its significance. The work makes a crucial contribution to our rethinking of Australian military history, and is a fresh bulwark against those who doubt the extent or depth of the frontier campaigns. Gapps’s developing oeuvre should also add to future understandings of what constitutes resistance, revolt, and war itself.

Comments powered by CComment