- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Natural History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Protect the long view’

- Article Subtitle: Deep histories, short futures

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Tasmania is in a new age of fire,’ writes Andrew Darby in an article for The Guardian. The fires in February, which came close to destroying ancient Huon pines in the takayna/Tarkine and pencil pines near Cradle Mountain, were started by a dry lightning strike, as were the fires which tore through the Grove of Giants six years ago. Lightning strikes were once responsible for less than 0.01 per cent of bushfires in Tasmania but now account for the vast majority, an eight thousand per cent increase over a decade. ‘Quite honestly,’ says Jon Marsden-Smedley, a former fire management officer interviewed by Darby, ‘I don’t know of any other climate-change parameter that is as dramatic.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Dave Witty reviews ‘The Ancients: Discovering the world’s oldest surviving trees in wild Tasmania’

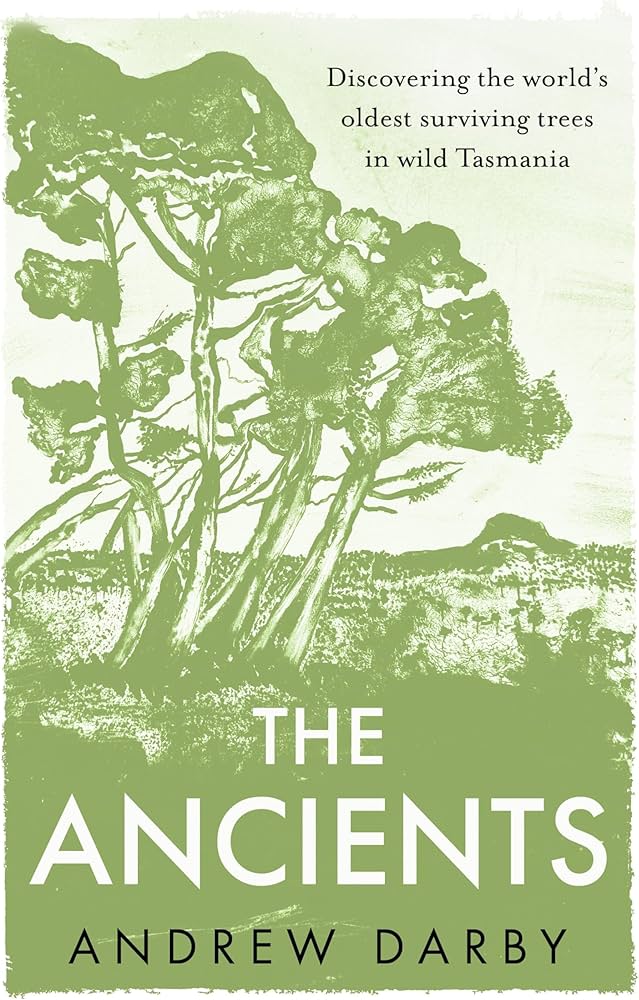

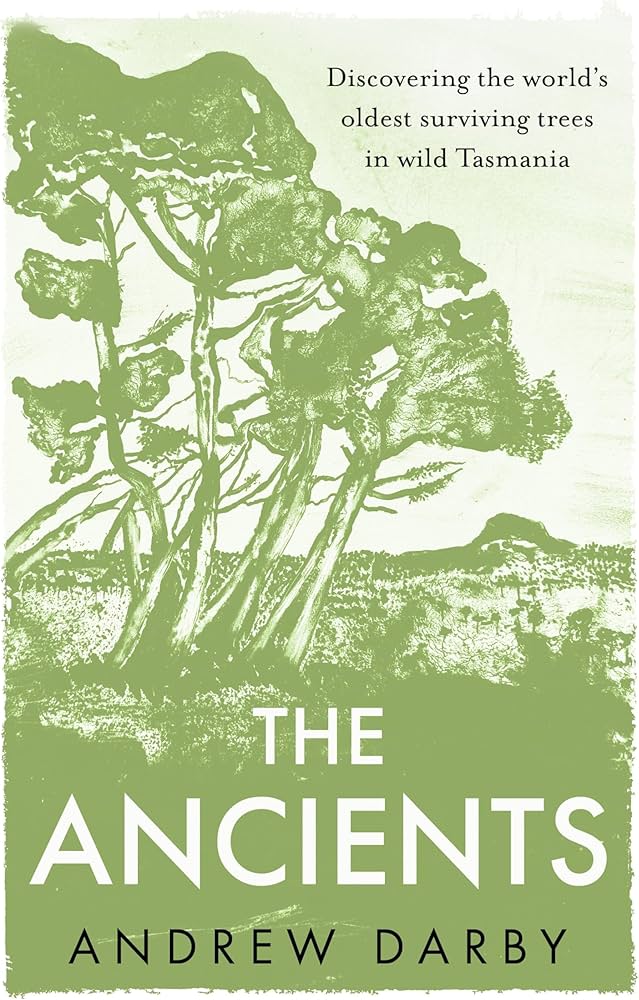

- Book 1 Title: The Ancients

- Book 1 Subtitle: Discovering the world’s oldest surviving trees in wild Tasmania

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 297 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761069239/the-ancients--andrew-darby--2025--9781761069239#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Such climatic shifts should be global news. Dry lightning fires are more intense and can ignite anywhere, a potential death sentence for species like the King Billy, pencil and Huon pines, the King’s lomatia, tanglefoot, and myrtle beech. These are the ‘ancients’ of the book’s title: paleoendemic trees that are both individually ancient (a King’s lomatia clone has been dated to almost fifty thousand years) and evolutionarily far removed. These ancient trees have shaped the Tasmanian landscape for millions of years, their lineage traced to Gondwana. Because they have not evolved with the same adaptiveness to fire as eucalypts and acacias, it is possible that some of these ancient species may become extinct within our lifetime.

For his first book, Harpoon (a 2007 book about whaling), Darby’s narration began on the shores of Tasmania’s Bruny Island. Flight Lines, his second book, took him along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, from South Australia to Wrangel Island. Now, wanting to pay ‘homage to this extraordinary island where I live’, he returns to Lutruwita/Tasmania.

When asked his inspiration for writing The Ancients (in an interview with his publisher Allen & Unwin), Darby cited the alarm he feels for this ‘new climate change-induced phenomenon of the dry thunderstorm’. Venerable is the term he uses for these ancient species under threat; vulnerable would be the obvious counterpoint. King Billy pine, a tree of the Mesozoic, takes up to a thousand years to recover from wildfire. With another intense fire during that period, the species could be entirely wiped out.

Until now, the popular literature on Tasmanian trees (think, Anna Krien’s Into the Woods [2010] or Richard Flanagan’s Out of Control [2007]) has tended to focus on the logging wars. This has left eucalypts taking centre stage at the expense of the paleoendemics, a failing in which I am complicit. (My book What the Trees See told Tasmania’s story through the blue gum rather through than the King’s lomatia or Huon pine.) Yet there is something unique about the Tasmanian landscape: conifers warped into Bonsai-like poses; pandani growing like Seussian trees. A book on Tasmania’s extraordinary vegetation is long overdue.

With its evocative cover (a lithograph of a wind-sculpted pencil pine by Hobart-based artist Kaye Green) and its weighty title, I was expecting The Ancients to be more lyrical, its inspiration taken from the reverie of Eric Rolls, say, or the poetic craft of Robert Macfarlane. Some sections read more like long-form journalism, the momentum carried not on lyrical waves but on interviews with scientists and experts in the field. Darby can spin a delicate phrase; but he often favours other people’s words above his own. He is also a wonderfully passionate advocate for nature. While I greatly enjoyed his previous book, Flight Lines, it was his interview on the subject with the ABC’s Richard Fidler that, for me anyway, elicited the most profound response. His love for shorebirds almost brought me to tears. In print, his journalistic impartiality can act as a literary restraint.

The Ancients is well-researched, insightful, and deeply immersive, but it never reaches the same emotional heights as Flight Lines which, like Inga Simpson’s Understory (2017), finds symbolic crossover between the author’s personal life and its subject (in this case, the migrations of shorebirds morphing into an equally formidable journey, that of the author’s battle against Stage 4 cancer). The personal side is less pronounced here, but it does occasionally surface, often through amusing descriptions of a seventy-year-old negotiating difficult terrain. In these moments, his style is reminiscent of that of Harry Saddler, but there is also a seriousness to these asides. Like the ancient trees he describes, Darby is surviving against the odds, kept alive by the miraculous effects of immunotherapy.

My favourite parts of the book occur when the narration, like its peripatetic narrator, begins to wander. Appropriately enough, this more discursive style begins when Darby visits Meander Falls. The style in these sections is not unlike that of another book about roaming: Simon Cleary’s Everything is Water (reviewed in ABR, August 2024). But while Cleary’s descriptions of Maiwar, the Brisbane River, convey a sense of timelessness – largely through his hypnotic, elliptical prose – this deep, multi-layered impression of time is not as well realised in The Ancients.

It is no easy feat to translate millennia onto the page, let alone millions of years; modern minds are poorly attuned to considering time periods longer than a decade. To communicate the ancientness of these trees is an ambitious goal, but one that seems central to the book’s premise. As Darby writes at the end of the fourth section: ‘This is Huon’s lesson for us. Protect the long view, deep into time.’ This is the warning implicit in the book: that trees familiar to dinosaurs, their marathon lives one of relative stability and infinitesimally slow decline, are now facing an abrupt demise. A thunderclap and they could be gone. I enjoyed The Ancients, but it fell short in conveying the immensity of the trees’ lifespans, not quite delivering the trans-historical story suggested by its title.

Comments powered by CComment