- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The sacred and the profane

- Article Subtitle: A grandly enigmatic novella

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

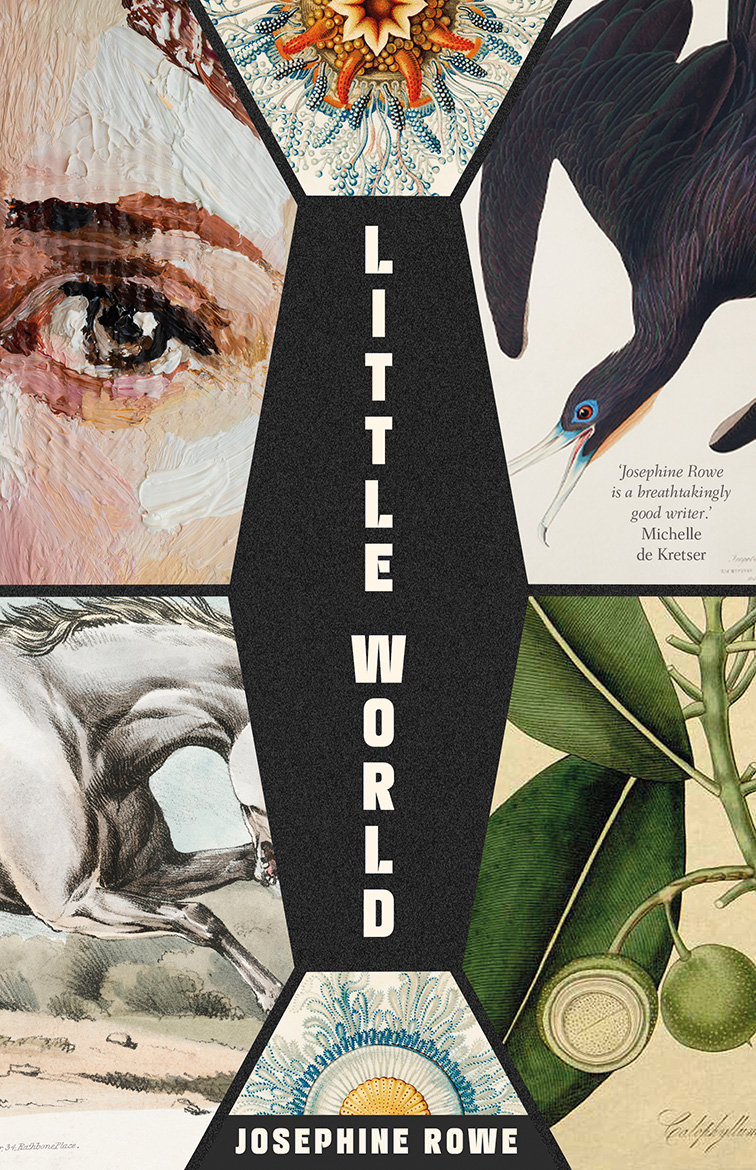

Josephine Rowe’s third novel, Little World, is a little novel, at least in terms of its length, which resembles that of a novella. Little World is also about a little person, specifically a child, or rather, the preserved corpse of a child, said to be a saint. There is nothing small, though, about the novel’s impact, which is grandly and enduringly enigmatic.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Maria Takolander reviews ‘Little World’ by Josephine Rowe

- Book 1 Title: Little World

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $27.99 pb, 144 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781760645427/little-world--josephine-rowe--2025--9781760645427#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

An omniscient narrator immediately – befitting the novel’s brevity and brisk pace – provides a description of the child, who has turned up in the Kimberley in a coffin made of tamanu, the timber-of-choice for Pacific canoe-building. The girl’s sainthood is unverified, but a solicitor’s letter suggests that her ‘incorruptible body, delivered of all evidence of earthly violence and earthly suffering, was still typically considered grounds enough for beatification’. However, the omniscient narrator, who is a character in her own right – sometimes blunt and detached in her storytelling style, sometimes lyrical or droll, sometimes invested and enraged – is clearly averse to humouring any religious fantasies. In a scathing intervention that brooks no ambiguity, the narrator announces that the child ‘is not, has never been, a saint. That hardly needs saying. She is a kid in a box tens of thousands of miles from where she died, with no way back to that place.’ After providing a sparing account of the circumstances of the girl’s death – she was raped as a fourteen-year-old in an assault that proved fatal – the narrator comments on the ‘perverse’ irony of the girl’s status as ‘Incorruptible’. ‘That her flesh did not retain any trace of violence,’ the narrator reflects, ‘was a betrayal.’ This girl’s dead body, while alleged to be that of a saint, is marked less by the sacred than the profane.

As for the child’s provenance, while her clothes are suggestive of early-eighteenth-century Europe, it appears that the girl is from Nauru: a country that was once home to a leper colony (before it became a dumping ground for Australia’s asylum seekers); a country ‘eviscerated’ – in the narrator’s terms – by phosphate mining; a country in which the original Micronesian and Polynesian cultures were devastated by different imperial powers, from the British to the German to the Japanese to the Australian. Women and girls, as everywhere in colonial contexts, were at the cutting edge of what might politely be called intercultural relations. Indeed, a bit of research – and this is a novel marked by an elliptical quality that rewards googlers – tells me that the first German administrator married a fifteen-year-old Nauruan girl.

Perhaps that culturally mixed colonial history is why, when the allegedly beatified girl died, she ‘could swear in four languages’. Now, having been relocated to the Kimberley, the narrator cheekily reveals that the girl can swear in five. This raises the question: is the girl in the box dead, or is she somehow still alive? The narrator attempts to explain: ‘To speak of consciousness: complicated.’ Our narrator, in lyrical and oblique mode, goes on:

Evening, when the house is thrown open to the westerly, and some skerrick of it steals in through the slats of tamanu, rustles the layers enveloping her within the box, it can’t exactly be said that she feels the breeze cool on her skin. Only a recognition that there is a breeze, that it comes from the west, that such a breeze would feel cool upon the skin.

Here, we find ourselves in the literary territory of magical realism, a narrative space of fantasy mixed with irony, a nexus rich with ambiguity and, consequently, demanding rigorous engagement. That demand is consistent with the omniscient narrator jostling readers out of complacency, asking not for blind faith but for attention and interrogation. If the girl is not a saint, how do we account for her presence? In many respects the magical realist story is like a ghost story, in which the ghost reveals some unresolved grief or grievance from the past, though the edgy irony of the magical realist narrative tends to reveal an anger that comes from wrongs perpetrated not in a narrative world but in historical reality. Think of Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987), which exposes the horrors of slavery, or Evie Wyld’s The Bass Rock (2020), which addresses the terrors of misogyny.

As it turns out, the girl in the box represents different things to the different characters who come into her orbit, though all of those meanings smack of historical injustice. Chronologically speaking, the first of these characters is Kaspar Isaksen, a Norwegian leprosy researcher in Nauru, who drinks himself to death, haunted by the fate of the people under his care. He bequeaths the beatified girl to a co-worker from his Nauruan days.

That colleague, a man called Orrin Bird, lives in the Kimberley, where the novel begins. Orrin is a solitary man who believes only in the gods of ‘the Dirt and the Wet. And yes, the Dry.’ There are also ‘the gods Salt and Reef and Ant Mound’. Through Orrin, the narrator draws our eye to a primevally powerful environment, ravaged by colonialism.

The third character to come into contact with the girl’s corpse is Mathilde Eberhart, the Australian daughter of German migrants, who suffered from religious persecution, forced into a home for ‘Girls in Moral Danger’ when she fell pregnant. Mathilde’s story is the longest in this book, which is first and foremost, as the dead girl suggests, about the damage history has done to women and girls.

The stories of these three characters form the narrative trajectory of Rowe’s book, but the child’s corpse is the enigmatic kernel. As with Yorick’s skull in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the black page in Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy (1759), and Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899), you won’t forget her.

Comments powered by CComment