- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Scorpion power

- Article Subtitle: A handsome reissue of Mary McCarthy’s memoir

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

How literature loves to corral its characters in defined, even confined spaces and closed societies. Chaucer anatomised his ‘sondry folk’, his pilgrims, as they gathered in Southwerk’s Tabard Inn. A secluded Florentine villa was Boccaccio’s retreat for storytelling, while the Black Death raged in the countryside. Agatha Christie, who understood immurement-by-loss, lent a lethal frisson to the English country house and the European rail carriage. Umberto Eco chose a monastery for his Name of the Rose intrigue. As recently as 2023, Charlotte Wood brought the protagonist of her novel Stone Yard Devotional into a convent, to confront herself and witness another portentous environmental and social plague – this one of mice.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Morag Fraser reviews ‘Memories of a Catholic Girlhood’ by Mary McCarthy

- Book 1 Title: Memories of a Catholic Girlhood

- Book 1 Biblio: Fitzcarraldo Editions, £14.99 pb, 266 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781804271650/memories-of-a-catholic-girlhood--mary-mccarthy--2025--9781804271650#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

As a technique, the concentration, the close focus, works. It lures the reader with a promise of revelation, a lens on the unusual, the exotic, the forbidden, sometimes even the transcendent. As a marketing device it is timeless – and brilliant. Unsurprising, then, that independent British publisher Fitzcarraldo should bring out a new edition of Mary McCarthy’s classic Memories of a Catholic Girlhood (first published 1957), in the chaste white/blue gatefold edition Fitzcarraldo’s designer, Ray O’Meara, favours.

The cover of my 1983 Penguin edition of McCarthy carried a candle-lit porcelain Virgin on a small pedestal, elevated above an entanglement of rosary beads. The 2025 Fitzcarraldo edition is subtler, but its pristine white cover and custom serif typeface (also called ‘Fitzcarraldo’, in ‘International Klein Blue’, the blue repeated on the inside of the elegant gatefold) is nonetheless evocative of the prayerbook young Catholic ladies carried as they walked in Sodality of Our Lady processions towards the statue of the Virgin Mary in the grotto outside the convent chapel (mine had a gleaming, opalescent cover).

So, the stereotypes linger, even if in an attenuated or ramified way: Mary was a Catholic, so her girlhood must have been one of stringency, indoctrination, aspiration, repression, austerity, fragile beauty, chastity, even possibly (a more recent, if retrospective, fear) abuse.

Mary McCarthy couldn’t be contained, or explained by any stereotype. Her girlhood was indeed one of extremes: orphaned at the age of six in 1918 (her parents died of ‘Spanish Flu’), she suffered loss, sadistic extended-family violence, poverty, luxury (vicariously), institutional regimes and rules (which she broke), enforced alienation from her three brothers, a bewildering succession of schools (some Catholic), and an equally disorienting alternation of modes and degrees of care, from her Catholic, Protestant, Jewish extended family, most of whom had no idea how to handle or appreciate the girl entrusted to them.

And out of it all, Mary McCarthy wrote.

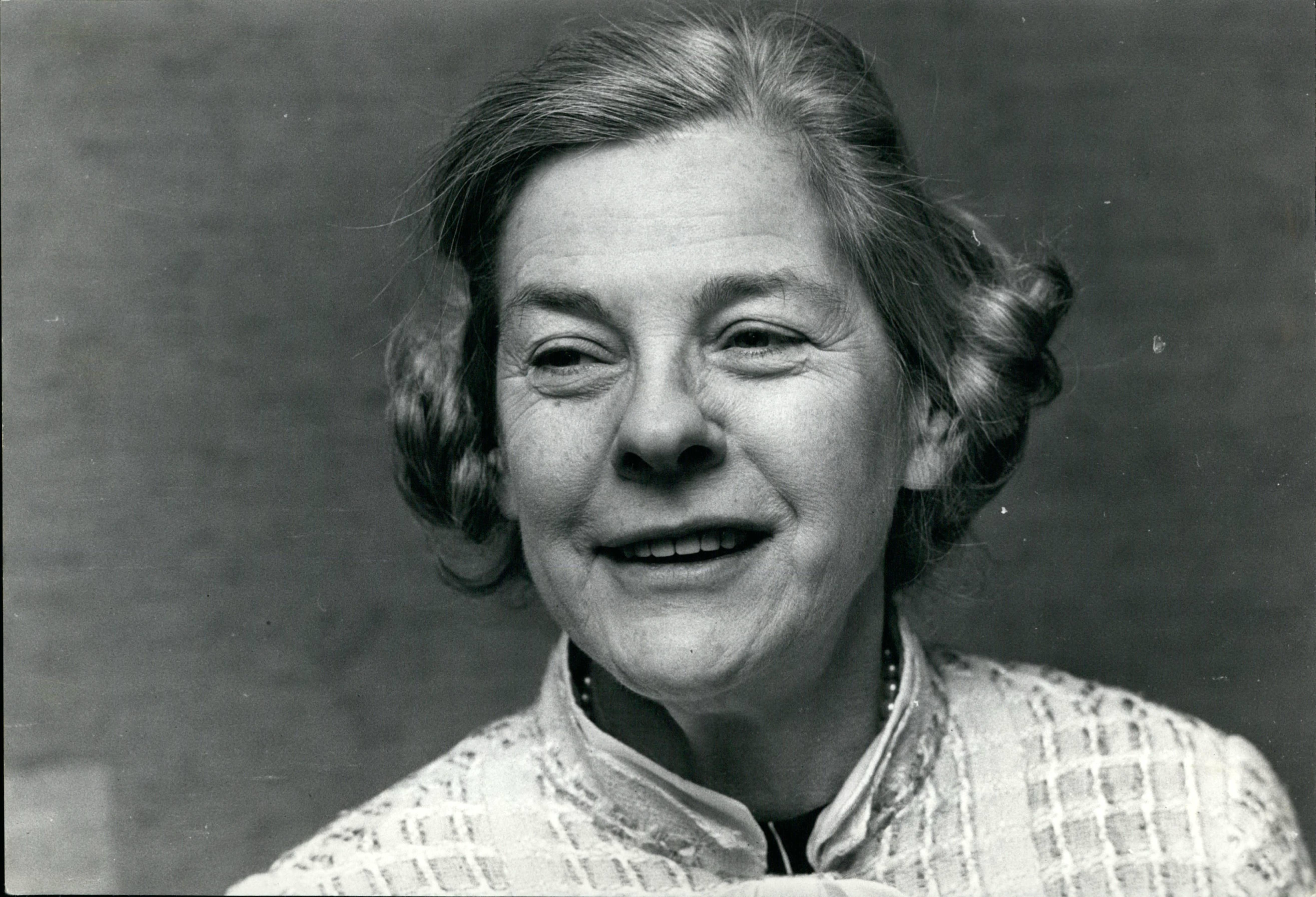

Mary McCarthy, 1973 (Keystone Press/Alamy)

Mary McCarthy, 1973 (Keystone Press/Alamy)

To recommend Mary to twenty-first-century readers, Fitzcarraldo cannily chose Colm Tóibín, the Irish-born, America-savvy writer also scarred by his past (an early stammer, induced by familial loss), and acquainted with the legacy of Catholicism. Tóibín’s Preface deftly establishes a sympathetic context for McCarthy, including in it the spectacular condescension of some of the literary warriors of McCarthy’s time. Tóibín clearly relishes, for example, the irony of Norman Mailer’s allowing that it was ‘possible now to conceive that McCarthy may finally get tough enough to go with the boys’.

Tough enough? McCarthy wielded prose with the deadly precision of a markswoman-assassin, and Tóibín acknowledges as much. He is clear-eyed about her ferocity. Quoting a New Republic assessment of Memories (‘Miss McCarthy’s new book has a quality of gentleness and warmth for which her earlier fiction scarcely prepared us’), Tóibín disagrees:

Compassion and gentleness … were often the very things absent from the book. For example, in one of the early pages, McCarthy wrote: ‘My grandmother, Elisabeth Sheridan, looked like a bulldog … a cold, disputatious old woman who sat all day in her sunroom making tapestries from a pattern, scanning religious periodicals, and setting her iron jaw against any infraction of her ways.’

(‘Making tapestries from a pattern’ – how the precision of that strikes! The woman couldn’t even invent needlework for herself.)

Tóibín also acknowledges the scouring self-diagnoses that characteristically accompanied many of McCarthy’s demolitions. She reconsidered, almost neurotically. Here’s the confession that rounds out the ‘Yonder Peasant, Who Is He?’ chapter:

Nevertheless, in one sense, I have been unfair here to my grandmother: I show her, as it were, in retrospect, looking back at her and judging her as an adult. But as a child, I liked my grandmother; I thought her a tremendous figure. Many of her faults – her blood-curdling Catholicism, for example – were not apparent to me as faults. It gave me a thrill to hear her go on about ‘the Protestants’ and the outrages of the Ku-Klux-Klan; I even liked to hear her tell about my parents’ death. In her way ‘Aunt Lizzie’, as my second cousins used to call her, was a spellbinder.

As was her granddaughter, born to attract and hold an audience. Elisabeth Hardwick, another writer of devastating prose, praised McCarthy’s stories thus: ‘They were indeed a sensation of candor.’

So, reader beware: sixty-eight years after they were written, Mary McCarthy’s ‘Memories’ retain a scorpion power to sting. And it is difficult to place the stinger herself. She lunges, skewers, then retreats. Her ‘Memories’ have a Rashomon quality, with ‘on the other hand’ musings appended to many of the chapters, passages of self-doubt (or further self-display?) that question the veracity of her memories and the kindness, or justice, of her conclusions. She interrogates herself. After one chapter (‘The Blackguard’), full of intense speculation one can only call theological/philosophical, McCarthy writes, ‘My curiosity was awakened … Though I am still suggestible, I have begun to exploit this quality and play, deliberately, to the gallery.’ A thespian instinct, then, one she owns.

The chapters themselves were written over a decade, some published as self-contained pieces in The New Yorker and Harper’s Bazaar. So don’t expect sequence or continuity. This is an eccentric Bildungsroman, all over the place (often literally). McCarthy ranges between Seattle and Minneapolis, where her Protestant/Jewish and Irish Catholic/American grandparents lived, and zigzags across times schemes, religious affiliation and disaffiliation. Her vivid depictions of family and teachers (wicked, whacking Uncle Myers and complicit Aunt Margaret, and the intellectual ‘Ladies of the Sacred Heart’ etc.) also have a double quality – a shadow image acquired as McCarthy rethinks and revises them over time. There is poignancy to this. With a pen so adept at fixing sharp images, McCarthy is still human enough to score and smudge her enamelled surfaces with doubt, and, occasionally, gratitude. One of the unforgettable characters (for the reader as well as McCarthy the pupil) is ‘Highland Scotswoman’ Miss Harriet Gowrie, a teacher with a passion for the classics and a closet smoking habit. (Can it be accident that the names ‘Miss Harriet Gowrie’ and ‘Miss Jean Brodie’ echo one another?)

The virtuosic chapter in which Miss Gowrie features is a blend of tragedy and rueful affection. Miss Gowie produced the play Marcus Tullius in which McCarthy triumphed at the Annie Wright Seminary in Tacoma (sent there by her benevolent Grandfather Preston after Mary had strained first the Sacred Heart nuns and then a public high school). Miss Gowrie’s Latin translation is ‘buckram’ (stiff, utilitarian) to sixteen-year-old McCarthy but the woman herself is a shimmering portrait of intellectual and vocational ambition, yearning, and constrained womanhood. Like the Voltaire-reading nuns, the homebound wives, and the well-intentioned Protestant grandfather, she is indelible, fallible, and unforgettable.

As is Mary McCarthy herself.

Comments powered by CComment