- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bill’s mental metronome

- Article Subtitle: The education of the young Bill Gates

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘The unpredictability of biography,’ writes Timothy Snyder in On Freedom, ‘flows into the unpredictability of history.’ This is self-evidently true of leaders who, like William Henry Gates III, also known as Bill Gates, the co-founder of Microsoft, initiate the kinds of change that are destined to be viewed as history. Their lives, like all of ours, are amply shaped by contingency and event, the ‘what if’ moments and decisive decisions, both their own and others’. The mystique of what might never have been, or might have been otherwise, is powerful. Even though there are many alternatives and competitors, it is hard to imagine personal computing evolving as it did without the ubiquitous Microsoft products that have shaped the world. Consumer technologies such as these, which were also an early form of AI, have become all but invisible. Gratifyingly, the Microsoft co-founder and former CEO’s first autobiographical instalment, Source Code, is liberally sprinkled with fork-in-the-road moments and tensions. It is a hero’s journey narrative, blending memoir with personal case studies in business leadership and strategy. The book begins with Gates’s early childhood and ends in 1978. The author foreshadows a further two volumes.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Judith Bishop reviews ‘Source Code: My beginnings’ by Bill Gates

- Book 1 Title: Source Code

- Book 1 Subtitle: My beginnings

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $55 hb, 328 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780241736678/source-code--bill-gates--2025--9780241736678#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

I am old enough to remember the arrival of the first computer in our home: a MicroBee personal computer kit assembled by my father circa 1983, on which my brother and I would play endless games of Space Invaders. There was also a Texas Instruments ‘Speak and Spell’ toy that, long before the current language learning apps, spoke words aloud for children to type (in American spelling) and to be automatically corrected. Source Code describes at length the emergence of personal computing at a time when massive mainframes were still the main model. Personal computers started out with extremely simple software (getting a computer to print 2+2 = 4 was a breakthrough, Gates recounts). This software was written in a programming language called BASIC, which lived up to its name. Gates, his schoolmates, and university student collaborators spent countless hours adapting BASIC to run on different computer chips to perform tasks such as calculating traffic flows and optimising school schedules. That was how Microsoft began. As a teenager, Gates had an overly forthright, ‘hyperkinetic’ manner of speaking to his elders, an often monomaniacal focus, and a tendency to rock to his mental ‘metronome’. ‘If I were growing up today,’ he writes, ‘I probably would be diagnosed on the autism spectrum.’ The young Bill, Gates recalls, was grateful to be treated by others in ways that reinforced his intellectual strengths, tempered his unruliness, and supported his social and emotional development.

In the early 1970s, personal computers sold in the hundreds or thousands. Only fifty years later, AI models are writing their own code and personal computers are an indispensable tool in the homes and offices of the developed world. The second half of Source Code is full of inside perspectives into Microsoft’s crucial early deals, and case studies of the cut-throat business environments and down-to-the-last-penny financial situations that the start-up endured to succeed. For readers not inherently interested in business narratives, the book nonetheless provides a window into that world of preoccupations and existential dramas.

The laid-back style of the book, and its humble and at times self-deprecating reflections, are unexpected, given the stature of the writer. I had a strong sense of Bill Gates as a well-loved uncle, regaling young listeners with his boyhood coding escapades and cocky encounters with bemused but supportive professors and businessmen who might have thought the kid odd but appreciated his talent for making the earliest computers do things that others couldn’t, or wouldn’t, have imagined. If the whiff of greasy pizza boxes and unwashed sheets comes in waves through 300-plus pages, these were the detritus of Gates’s countless all-nighters spent at computer terminals as Microsoft (then Micro-Soft) emerged as a company. History, it turns out, is made of such things.

For those readers less inclined to sit at the feet of Uncle Bill to hear how a company is made, there is a further historical dimension to Source Code that may yet be of interest. It could turn out to be a key document in any future account of the seismic shift now underway in technocratic visions and values and the uses of associated mega-wealth. Knowing that biography flows into history, it is hard not to compare Gates’s gentle yet firm and social-minded upbringing, as described in Source Code, with Elon Musk’s, summarised in a blurb for the eponymous biography by Walter Isaacson: ‘When Elon Musk was a kid in South Africa, he was regularly beaten by bullies … But the physical scars were minor compared to the emotional ones inflicted by his father, an engineer, rogue, and charismatic fantasist.’

On 20 January 2025, several global tech billionaires rallied behind a charismatic fantasist at his presidential inauguration and began to align their interests with his own. One of the tech leaders in Trump’s orbit, Satya Nadella, is the current CEO of Microsoft. Some of those tech interests are now playing out in bullying trade moves involving Australian media organisations. But the new president’s agenda also included the demolition of US foreign aid, formerly provided through an organisation known as USAID. Its workers described having to walk away from communities where they provided life-saving medical aid, knowing people would die. Does Trump’s tech gang give a damn?

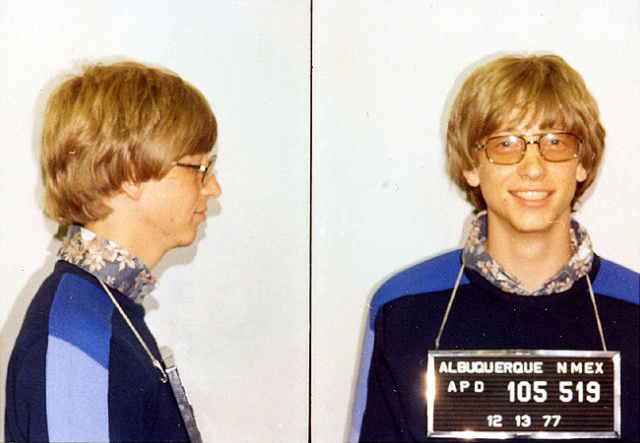

Bill Gates, 1977 (courtesy of New Mexico Police Department)

Bill Gates, 1977 (courtesy of New Mexico Police Department)

Bill Gates is known for another historical contribution beyond the Office suite of products, operating systems, search engines, and related ventures. This is the philanthropic foundation which is now known as the Gates Foundation. Until recently, Gates headed it up with his former wife, Melinda French Gates. The Gates Foundation website records that in the year ending 2023, it provided $7.7 billion in charitable support for causes including reducing poverty, women’s economic participation, maternal health, and vaccination. As Sydney-based philosopher Gwilym David Blunt puts it in a blog post titled ‘A Mirror for Tech bros’, ‘This makes [the foundation’s aid] comparable to a major developed state such as Australia in terms of foreign aid spending, but it tends to be more effective and influential.’ The Gates Foundation’s apparent underlying calculus is to save the most lives per dollar spent, which is why Gates has been claimed by some members of the effective altruist movement as one of its number.

This part of the Microsoft founder’s story is for a future book, as the Acknowledgments note. However, Source Code at several points underscores the strong familial values of charitable giving that found later expression in the Foundation’s work. Gates writes, ‘If my parents sound a little virtuous and resolute about volunteering, giving back, and all that, I can’t help it. That’s who they really were.’ Gates describes a conversation with fellow Harvard student Steve Ballmer (later his successor as Microsoft CEO) in which they ‘hashed out the benefits of working in government versus for a company, and which of those options would enable us to do more to improve society and have a greater impact on the world’. A note at the end of the book states that all profits from its sale will go to a charity in which his mother took leading roles. ‘It was my mother,’ Gates writes, ‘who regularly reminded me that I was merely a steward of any wealth I gained.’

Many of the tech billionaires who lined up behind Trump do not, to put it mildly, seem to share the desire for a legacy rooted in philanthropy – the love of humankind. Their techno-optimism has a very different cast. Watching their political dramas from afar and reading this book, I find myself speculating on how the current unpredictable tech billionaires’ lives will shape the next fifty years.

Comments powered by CComment