- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: What the Yirrkala Yolngu did

- Article Subtitle: Powerful storytelling from Clare Wright

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Yirrkala Bark Petitions were intensely significant in Australian politics, contributing not only to major changes in race relations in Australia but to the way Australians understood their country’s history and its future. Clare Wright’s Näku Dhäruk is a lucid, accessible, and engaging account of those 1963 Yolngu1 Petitions from the Yirrkala region of Arnhem Land: her book will deservedly be read widely and throw new light on the complex events which shaped this turbulent time. Yet as powerful and moving as this book is, it will leave some readers with lingering questions. This review will outline some of its many strengths, and will also suggest some of those questions.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Heather Goodall reviews ‘Näku Dhäruk: The Bark Petitions – How the people of Yirrkala changed the course of Australian democracy’ by Clare Wright

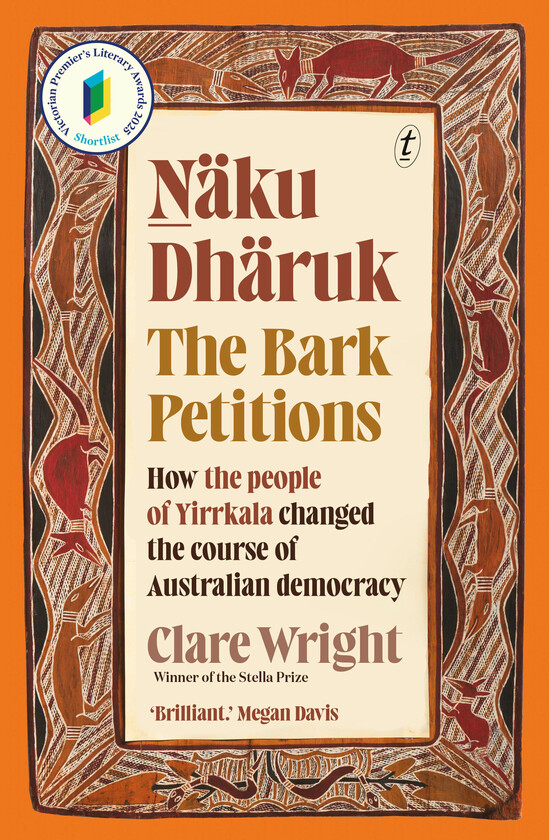

- Book 1 Title: Näku Dhäruk

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Bark Petitions – How the people of Yirrkala changed the course of Australian democracy

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $45 pb, 640 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781922330864/naku-dharuk-the-bark-petitions--clare-wright--2024--9781922330864#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Näku Dhäruk are known in English as the Yirrkala Bark Petitions. These are four rectangles of bark created in 1963 by the Yolngu people of the Yirrkala region in north-east Arnhem Land as a dignified but unshakeable protest against the proposed bauxite mining at Gove, on parts of their lands which were to be excised from the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve without any consultation with or consent by Yirrkala people.

Each of these four bark rectangles has at its centre a typed petition to the Australian Parliament, with identical wording in all four in two paragraphs, one conveying the petition in English and one in Gumatj, the Yolngu language spoken and read at Yirrkala. The petition is surrounded in each case by painted designs which are different on each of the four bark documents. When all four barks are read together, the designs represent the clans of the Yolngu at Yirrkala who own the lands that were to be excised. Each petition was signed by the same twelve people, some of them quite young, but each of whom had been authorised by the community’s senior people to represent the families from the clans whose land was affected by proposed excision for the mine within the Reserve.

The Bark Petitions were sent strategically: one to Robert Menzies, the conservative prime minister; one to Arthur Calwell, leader of the ALP; the remaining two to ALP parliamentarians and supporters, Gordon Bryant and Kim Beazley Sr. The text was formally read and presented to Federal Parliament on 14 August 1963.

The Yirrkala Yolngu had created these typed and painted documents when they discovered that the mine and the excision were approved, in secret, by the federal government, with the complicity of the authorities of the Methodist Church, which ran the Mission around which many Yirrkala lived. The Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve had supposedly been declared inviolate in perpetuity in 1931, to be used solely by its Aboriginal inhabitants to ‘preserv[e] their race’.

The 1963 delivery of the Bark Petitions and their role in furthering the nationwide First Nations demand for recognition of Land Rights have been documented before, as Tim Rowse has pointed out in The Conversation (10 October 2024). Wright, however, has gone much further than earlier accounts. As a resident at Yirrkala from 2010, she developed relationships with both Yolngu and white mission staff. She was able to draw on previously unused diaries and publications of the staff, as well as on archives, press accounts, and interviews. While these are certainly the sources of conventional histories, Wright has written this story with an exciting creativity – and it is a story in the most powerful sense of the word!

Wright’s style can be called creative non-fiction – without undermining the quality of her careful research. She has brought the skills of creative writing to bear on the many – often contradictory – documents she read and the memories she heard. Wright brings vividly into our imaginations the characters of the many conflicted allies around the Yirrkala Yolgnu. Her writing conjures up these players as fully rounded characters – their courage, their egos, their betrayals – and the tensions between them all.

There are a number of questions that Wright’s book raises for me. One concerns her stylistic decision to include what are apparently quotations from the written sources or from her interviews as italicised clauses within her own sentences, a decision which has also troubled Rowse. He has recognised the skill of her writing, likening it to Manning Clark’s innovations in historical style. I share Rowse’s concern about the italicisation: while there are some points at which Wright uses endnotes, most of the italicised clauses are not sourced, which leaves their origins unknown. I could not find an ‘author’s note’ explaining this decision. Although it soon becomes apparent that these italicised clauses are quotations, we are left wondering about where they come from. My other concern about these clauses is that, as readers, we have learned to understand italicised text as if it were to be emphasised, questioned, or otherwise noted. Our reading is then disrupted and uneven, constantly unsettled by the questions we might have about who spoke or wrote these words and to whom they were addressed.

Far more important than this question of style around italicisation is the absence of Yolngu people’s voices in this long book. There is a great deal about what Yolngu at Yirrkala did in 1963, gathered from the memories or writings of their non-Yirrkala allies and observers. There are important glimpses of the emerging civil rights movement in southern Australia, with individuals and organisations such as MPs Gordon Bryant and Kim Beazley Sr. (who was associated with Moral Rearmament), the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines (later FCAATSI), Shirley Andrews, Pastor Doug Nicholls, Faith and Hans Bandler, and many others. Wright introduces us to myriad shades of Christian, socialist, communist, and labour movement ideologies.

But there are few words from those Yirrkala Yolngu who were participants in the creation and delivery of the Bark Petitions. Galarrwuy Yunupingu, who was a very young man in 1963, encouraged Wright to tell this story, and he is quoted at the beginning and at the end of this book, with the use of italics, although not within Wright’s own sentences. Wright clearly spent much time talking with many other Yirrkala people, including the few surviving participants in the Petition’s creation, as well as with younger Yirrkala Yolngu about what they thought about these events today and what they had learnt about them from their elders. Yet we don’t really get to read any of this, although there is much commentary from the allies of the Yolngu about what people at Yirrkala were doing and saying. There are some encapsulated Yolngu people’s texts embedded in the book, without explication, which are narrations of what must be important Yolngu stories, but quite properly, as Wright had been instructed, only the public versions of such narratives are included, not the deeper meanings. While these texts may offer powerful insights into Yirrkala people’s intentions and goals, they are challenging for non-Yolngu readers to understand if there is no further discussion of their significance.

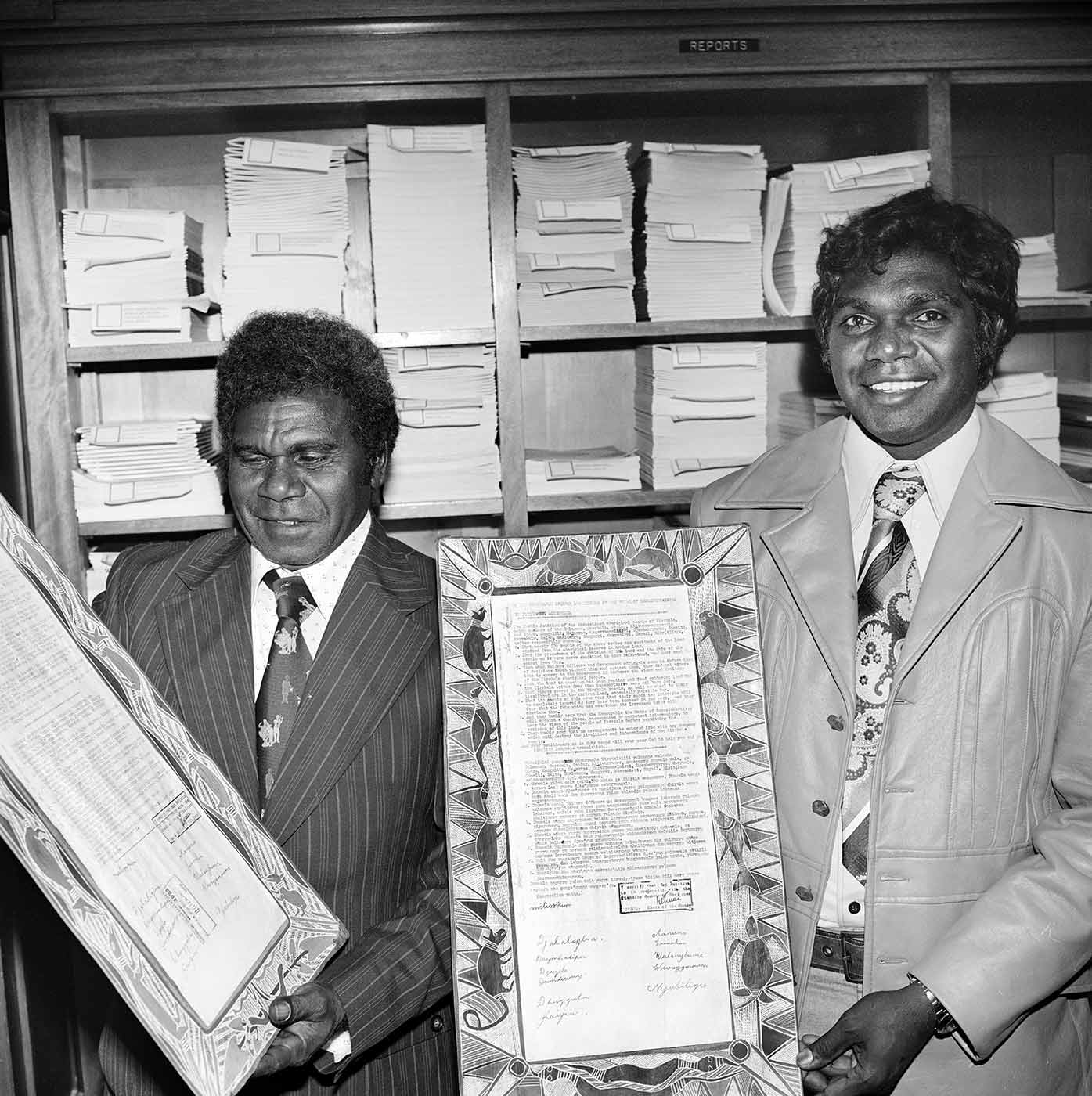

Silas Roberts and Galarrwuy Yunupingu, 1976 (courtesy of National Museum of Australia)

Silas Roberts and Galarrwuy Yunupingu, 1976 (courtesy of National Museum of Australia)

Despite such questions, this is a valuable book which will bring new understanding about these years. While there are many remarkable facets to this story, one section of Wright’s detailed history of the Mission offers insights into the weighty meanings these Bark Petitions carried.

While the bauxite mining plans were unfolding, there was another process going on at the mission. A new church was being built to replace the cramped existing church building. Edgar Wells has written that he asked the senior Yirrkala artists to contribute something to the new church, apparently hoping they might offer a design for a stained glass window. He insisted that their contributions should be ‘something of their own choosing’.

There were heated discussions among the Yolngu about what they might offer. The outcome was two tall panels designed and painted by Yolngu artists, which stood on either side of the altar, bearing complex designs which represented all the clans that made up the community and that belonged to the Country within which the Mission stood. This process took place over many weeks, with much discussion, all entirely between Yolngu men and women. They talked long into the nights about which designs should be painted, how they would be aligned and interrelated, and, finally, who were the right people to do the painting. These panels carried Yirrkala Yolngu law, about who belonged to that Country, about the bases of their authority, and about how they related to each other and to the law. These panels were more than a decoration in the new building. They were no less than a testament to Yolngu authority and standing; they comprised dominating elements of the physical space where the Church’s pastor ministered, as the photograph in Näku Dhäruk shows. The panels, in view at all times during the services for the Yolngu congregation, embodied the foundational role of Yirrkala law.

Over the months after the bauxite miners’ ground pegs were first discovered, marking out the potential ore bodies, it became clear to Yirrkala people that they had been deceived. The government had already secretly agreed that the bauxite mine should go ahead, colluding with the mining company and with the complicity of the Methodist hierarchy, but without any consultation or even information flowing to Yolngu at Yirrkala.

Faced with the failure of their own Church’s authorities to protect the Mission land, let alone the wider lands of the Yirrkala Yolngu, Edgar and Ann Wells became convinced that they had exhausted all avenues available to them. They encouraged Yirrkala Yolngu to make their case directly to the national government. Gordon Bryant, who was visiting the Mission at the time, suggested a petition to Parliament was an appropriate vehicle, and Wells explained the conventions of petition language.

It was Yirrkala Yolngu alone, however, who developed the content of the demand to Parliament and who decided that the powerful symbolism of their paintings for the new church, over which they had worked creatively for so long, should be the way that the petition would be embedded within their law of Country.

We are indebted to Clare Wright for this insightful book. Her work brings into clearer focus the many levels of meaning carried by the Bark Petitions, and no doubt opens up further directions for considering how those years changed Australia and Australians.

Only recently, in March 2025, the full bench of the High Court of Australia dismissed an appeal in which the federal government tried to avoid paying Yirrkala people compensation for the loss of their land when the Gove mine was approved. This has been a long struggle, but the pre-eminent Australian court has finally acknowledged the justice of the demands made in the 1963 Bark Petitions.

1. ‘Yolngu’ is a word meaning ‘person’ in the languages of north-east Arnhem Land. Like ‘anangu’ among Pitjantjatjara speakers in Central Australia, it has come to mean ‘Aboriginal people’ as opposed to non-Aboriginal people. It is used by Wright and in this review to indicate the Aboriginal people belonging to the lands in the Yirrkala region.

This is one of a series of ABR articles being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment