- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hiss and spray

- Article Subtitle: A fond sororal memoir

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I lament hearing the late poet Dorothy Porter (1954–2008) read in public only once, having devoured her work voraciously over the years. In the National Portrait Gallery, I once came across Rick Amor’s smallish 2002 portrait of Porter, which shows candid brown eyes framed by hawkish eyebrows inherited from her renowned barrister father, Chester Porter. ‘Chester Porter walks on water’ was her father’s vainglorious self-descriptor when he wasn’t monikered as ‘The Smiling Funnel-web’ at the bar (see Chester Porter, Walking On Water: A life in the law, 2003).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): A. Frances Johnson reviews ‘Gutsy Girls: Love, poetry and sisterhood’ by Josie McSkimming

- Book 1 Title: Gutsy Girls

- Book 1 Subtitle: Love, poetry and sisterhood

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $34.99 pb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780702268724/gutsy-girls--josie-mcskimming--2025--9780702268724#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Father and daughter each developed their own distinctive professional performative gifts. Porter’s face, like her poems, was an invitation without the spider, full of drôlerie, warmth, sensuality, and a dash of come hither, which, as sister and author Josie McSkimming reveals in her memoir, Gutsy Girls, sans moralising, got the poet into trouble as she resisted monogamous relationships. Porter’s poetry in turn thrived on formally inventive polyamory, though counterpoints between art and life can be overdrawn and were in fact ultimately undone by Porter herself when she moved to Melbourne to be with writer Andrea Goldsmith.

The narrator of Gutsy Girls is ‘Brat’ or ‘Brattle’, kid sister to the poet ‘Dod’. Homelife at semi-rural Mona Vale with two naturalist, left-leaning parents was bucolic but fraught. As young adults, Brattle and Dod (Josie and Dorothy) sought escape from their volatile father. Brattle embraced evangelical Christianity, later trading this for psychotherapy training, while Dod wrote herself into the Australian poetry pantheon. Their sister Mary is not given detailed focus, though she too was impacted by paternal angers. Brattle and Dod, six years apart, did not always get on: the former’s church-based dogma and homophobic judgements ensured distance. But as Brattle withdrew from decades of Big Religion, a humbled apostate, she recovered her relationship with the sister she patently adored.

One of the pleasures of this difficult-to-categorise book is that its author has unprecedented access to her older sister’s diaries and letters. These materials nuance what we know of the incendiary queer literary talent who made her mark on the Australian and international poetry scene.

Unpublished poems and poetry fragments are rare treats for aficionados and newcomers to Porter’s incandescent oeuvre. The young poet, aged seventeen, characterises her cool dead eye in loose iambic lines of imagistic sophistication: ‘I am cold like philosophy / and windswept brushstrokes / are my words. / I challenge smog/with its own barbiturate …’ (‘Untitled’, 1971). ‘I was flabbergasted when I read this poem,’ McSkimming writes; ‘no-one could compete with her’. We can’t determine the quality or quantity of the unpublished poems – this is no literary biography. But reading scattered fragments against the publications we know and admire confirms Porter’s early literary trajectory. Her first poetry collection, Little Hoodlum (1975), was published when she was twenty-one.

Via archives and remembered discussions, McSkimming provides compelling second-hand snapshots of the Sydney University Poetry Society, The Poetry Society of Australia, and the journal New Poetry. McSkimming’s chapter ‘Little Hoodlum’ portrays poets Bruce Beaver and Robert and Cheryl Adamson, the latter the ‘golden goose’ supporting Porter and publishing her first two collections under the Prism imprint. Elsewhere, Porter’s friendship with poet and sometime flatmate Judith Beveridge is tenderly drawn, while teaching colleagues – writers Drusilla Modjeska, Susan Hampton, and Jan McKemmish – reportedly provided crucial collegial sisterhood.

Porter published six more books before her queer gumshoe verse novel The Monkey’s Mask (1994) became a cause célèbre. This was the first crime thriller to be set in verse (though Porter had a verse-novel precedent with Akhenaten [1992]). The Monkey’s Mask won numerous awards and was widely translated and made into a film. McSkimming relates that ‘Dod’ said years later:

The Monkey’s Mask – the book for which I couldn’t even find a publisher – suddenly becomes a film, a play and the BBC have just done a radio dramatisation of it in London. I admit that at times I have deliberately done things to make money. But The Monkey’s Mask I wrote for the sheer hell of it and that is God’s truth – to create one great shitstorm and rock the literary scene to its core.

Maybe the ‘scene’ needed rocking; McSkimming reports that Dod was ‘sick of being knocked back for literature grants’ by institutional panels favouring male writers.

Porter’s letters are not formally cited (though a select bibliography appears at the back). This is a pity for literary biographers.

In a recent interview on Radio National’s Late Night Live, David Marr presented Gutsy Girls as biography. McSkimming did not correct him. Indeed, the contents page is chaptered according to Porter’s oeuvre. The opening chapter is titled ‘My Pocket Book of Prayer’ after a booklet made by six-year-old Dod for her Anglican, science-teacher mother, Jean. Closing chapters take the titles of Porter’s posthumous works, including the poetry collection The Bee Hut and rock-opera lyrics based on her unfinished collaboration with musician Tim Finn, later performed as The Fiery Maze. In principle, this works well. Modestly, too modestly perhaps, no chapters signpost McSkimming’s life. But this is memoir territory (McSkimming’s), with counterpointed biographical elements. ‘This is my story of losing and then finding both of my sisters … how I lost, and then found, the “hiss” and “spray” of my own voice,’ McSkimming writes, riffing on Porter’s question: ‘Do you hear / the fighting hiss / of this geyser / in me?’ (‘The Ninth Hour’, The Bee Hut).

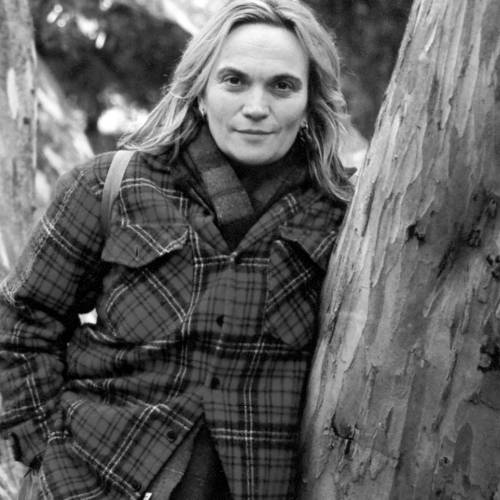

Dorothy Porter (courtesy of Black Inc.)

Dorothy Porter (courtesy of Black Inc.)

McSkimming notes that Goldsmith ‘was the first one to tell me that my own story was also interesting, even though I didn’t believe her. She patiently reminded me that the reason someone becomes a raving fundamentalist is not boring.’ Excellent advice, but aside from scenes in the chapter ‘Raising the Dead’ (named for Porter’s unpublished youthful novel), McSkimming’s religious oppressions are rarely dramatised, merely reported, eclipsed by scenes given over to the big sister star poet. I wanted less page-by-page hagiography of Dod’s poems, which are cast as lightning rods galvanising McSkimming’s nascent apostate journey. Notwithstanding such impact, no context is given for the author’s psychotherapy studies, which surely affected her abandonment of evangelical fealty.

Nonetheless, the writing improves noticeably when the author’s sense of self is disentangled from the living legend her sister became: ‘Dod was the link that held us all together and we broke apart like a white anted-stump.’ Elsewhere, Chester’s rages are well drawn as Jean and her daughters retreat, placate, fight back, and scatter, and the girls finally leave, Dorothy escaping to Sydney poetry land and romance, Josie into cassocked church arms, and Mary into an uneven marriage and veterinary science training. The portrait of Dorothy’s illness and last days is deeply moving, with a mature, reconciled Brattle hovering close.

Sixteen years after her death, Porter’s poetry still speaks for itself; her witty, iconoclastic poetics normalised (and continue to normalise) evocations of lesbian desire within an often rigidly heteronormative Australian culture (‘They don’t like us. / They won’t marry us.’ [‘VI. Crusaders’, The Bee Hut]). Porter also taught readers how to see (and make) poetic genres new. Hers was bold, brave work, not least because its early incarnations appeared on the eve of, and during, the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s. ‘No matter what happened, Dod always felt lucky,’ McSkimming writes. And as Porter herself wrote from her Mercy Hospital bed: ‘The sky – twilight sky – / is a wisping blue / friendly and unearthly … // … Something in me / despite everything / can’t believe my luck’ (‘View from 417’, The Bee Hut).

Comments powered by CComment