- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Definitely not present

- Article Subtitle: A man without a past

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Genealogy television programs like Who Do You Think You Are? often feature the celebrity gasping – in surprise, excitement, even alarm – as details of their family tree are revealed. Belinda Probert, a distinguished British-born Melbourne academic, had her own moment of incredulity when, four months after her father, Bill, was buried in 1994, her family received a letter from his nephew Denzil. For Denzil, Bill was not Bill, but Uncle Roy, who had spent his childhood living in an impoverished Welsh coal mining village in the Rhondda, and whose mother and siblings were alive when Bill’s children were born. All this was complete news to Bill’s family.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Joan Beaumont reviews ‘Bill’s Secrets: Class, war and ambition’ by Belinda Probert

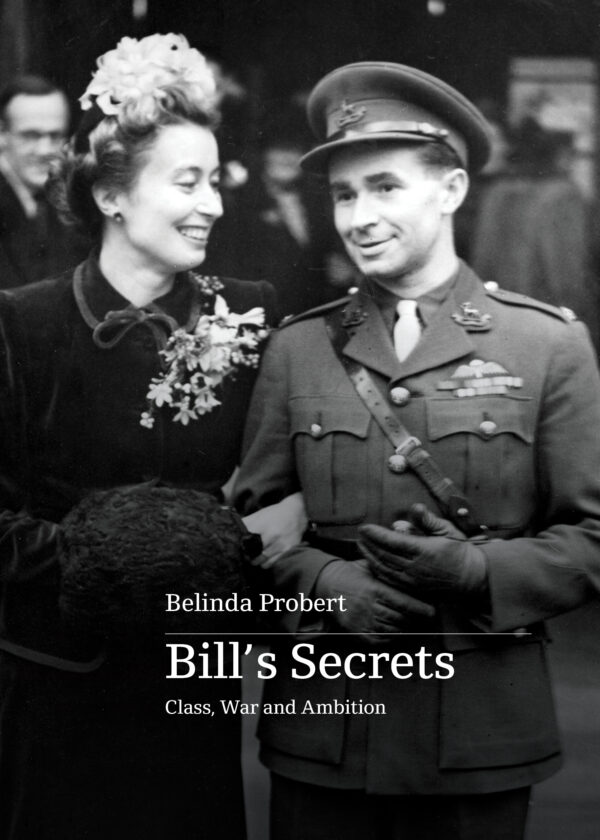

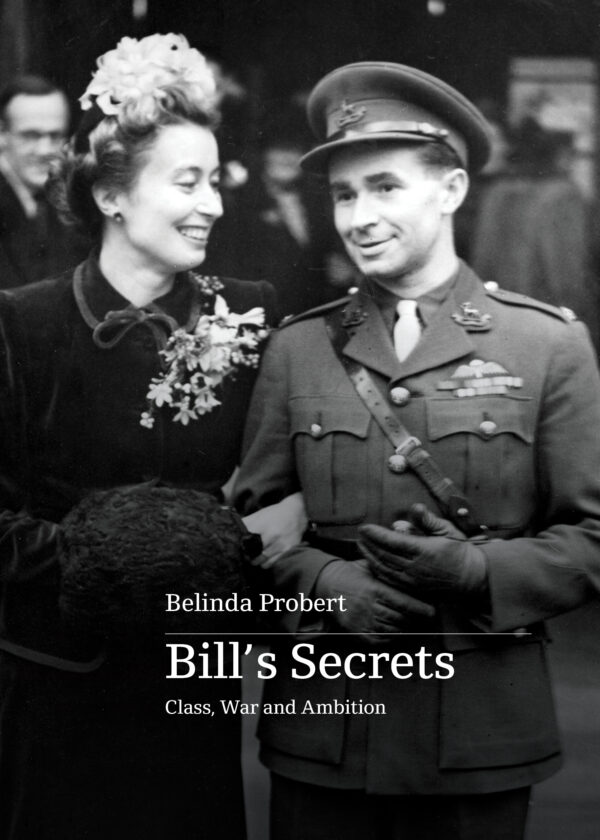

- Book 1 Title: Bill's Secrets

- Book 1 Subtitle: Class, war and ambition

- Book 1 Biblio: Upswell, $29.99 pb, 266 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780645984040/bills-secrets--belinda-probert--2025--9780645984040#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

It took almost thirty years before Probert embarked on the journey of understanding why Bill erased Wales and his family from his post-1945 life. Bill’s Secrets is the story of what she discovered about her father and herself on her detective hunt through military records, census data, travel, correspondence, and genealogical search engines.

Probert already knew that Bill had a distinguished record in World War II – he sometimes wore his parachute tie and had done ‘something brave’ during the liberation of France – and that he had gone on to be successful businessman after the war. He was fluent in several languages, loved all things French, had an impeccable English accent, wore double-breasted suits from Moss Bros, and drove a Jaguar. But there was, Probert’s research soon revealed, much more. Most notable was a childhood that was ‘unmistakably Welsh’. Bill was brought up in a dense set of family networks centred around the extraordinarily dangerous mining of coal. But he did not go to work down the coal mines in his early teens, as many of his peers did. Education and a scholarship provided him with an escape route.

Probert concludes that while at King’s College, London, her father discovered how much class and accent determined social status in England in the 1930s. Bill’s war service confirmed this – as did, it seems, his propensity for keeping secrets. It is still not clear what Bill was doing for much of the war, but his career included intelligence and special operations, in the Middle East, East Africa, and Madagascar. For a time, he worked with the Political Warfare Executive, a British clandestine body that disseminated propaganda intended to damage enemy morale and to sustain the morale of allies in Nazi-occupied countries.

In 1944, Bill embarked on a Special Operations Executive mission to France. He was parachuted into occupied France with the goal of training and organising Marquis groups in Ariège district. He led a successful attack by fifty Spanish Marquis troops on the German garrison in Foix, the administrative centre of the Ariège.

During his time with the British army, an organisation riddled with pernicious class prejudice, Bill decided to shed his working-class background. After he returned from France in October 1944, the family, his mother included, never heard of him again. Probert cannot fully explain the psychology behind this rupture, but she notes that the ‘willingness of Roy’s whole family to just let him go seems, in some ways, more unfathomable than his decision to abandon them’.

After the war, Bill probably continued his intelligence work, now with the Allied Control Commission, in Vienna, where he also met his wife, and Belinda’s mother, Janet. His subsequent business career was in international marketing, shipping, and trading, roles in which his language fluency and, presumably, intelligence contacts were an asset. In later life, Bill returned to Wales on a farming venture with one of his sons and finally retired to his beloved France.

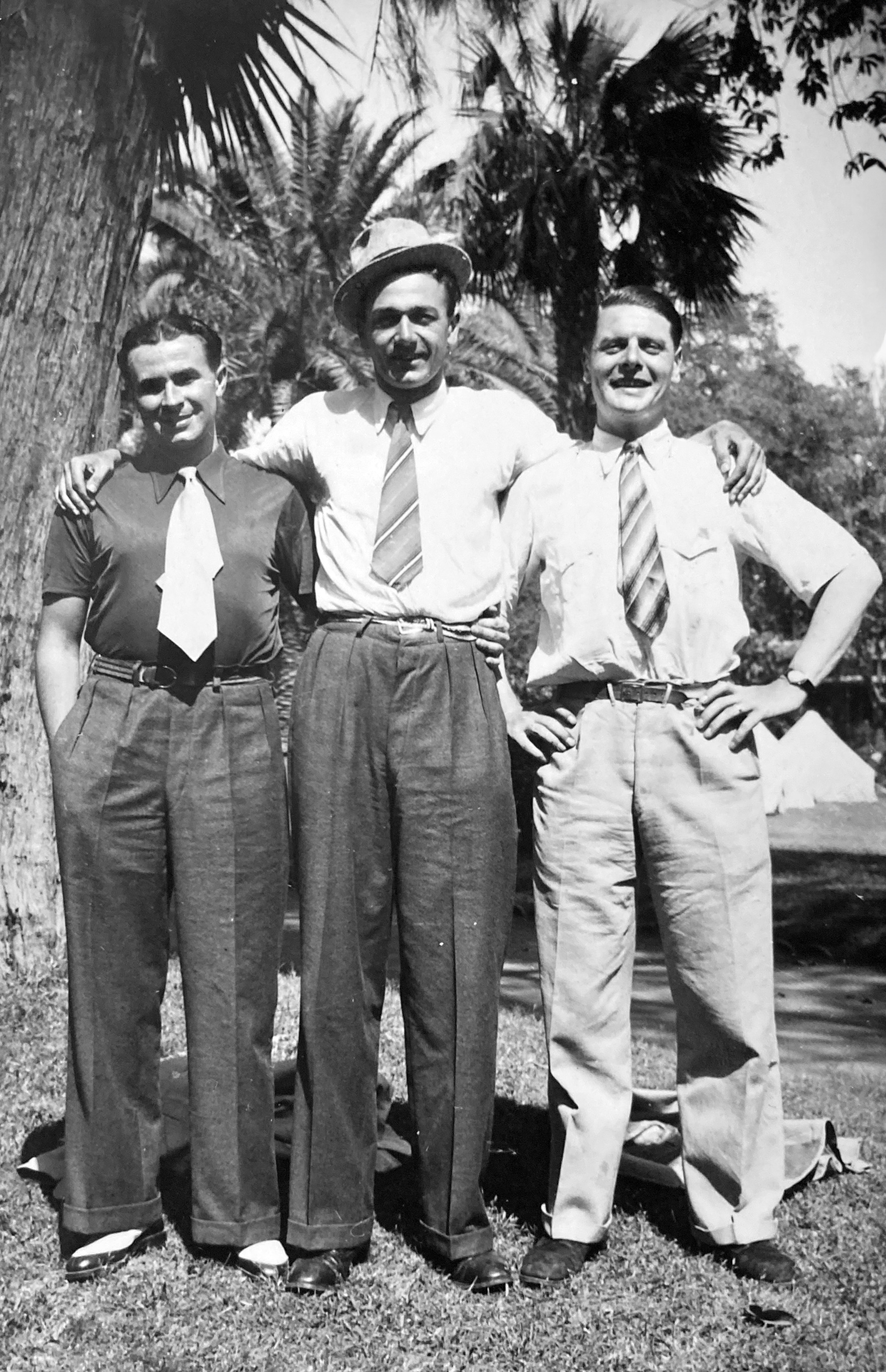

Bill Probert (left) with two spycatchers, Cairo (courtesy of Upswell)

Bill Probert (left) with two spycatchers, Cairo (courtesy of Upswell)

As this book progresses, we hear more about Bill as a father. He was ‘definitely not present’ for much of Belinda’s childhood, travelling on business, commuting to the city, and playing golf. She came to see her father as ‘difficult’, having unpredictable fits of anger. Probert’s brother thinks this reflected Bill’s growing frustration at work. She acknowledges that the cross-generational tensions caused her radicalisation during the political turmoil of the 1960s. But Probert concludes also that her father had a ‘deep-seated insecurity’. ‘If you have so painstakingly erased your own past, you must keep the lid firmly screwed down on many things.’ The psychological impact of his secrets ‘probably revealed itself when things over which he had no control got in the way of his desires and ambitions … he had few emotional means for dealing with [frustration]’.

As for Bill’s ability to compartmentalise his life so effectively and easily, Probert detects a common theme. Whenever Bill found life boring or could see nothing new ahead of him, he had to find something different to do, somewhere different to live. His identity seemed to reside in his being and his doing, the present and the future – never the past. Perhaps this explains his remarkable failure to contact any of his family when, late in life, he lived in Wales, only a short distance from them and, in some cases, their graves.

What about the legacy of World War II? Probert says that Bill’s silence about the war was not in any way unusual. Nor did it reflect, as far as she can tell, any particular trauma. On the contrary, she concludes, Bill enjoyed much of his war and gained extraordinary opportunities to enlarge his knowledge of the world. But we might ask whether Bill’s later anger and emotional distance were partly attributable to his war experiences – yet another secret? Intelligence and resistance work were stressful and dangerous. The citation for Bill’s Distinguished Service Order cites ‘fierce street fighting’ during the capture of Foix. ‘Major Probert entered the buildings alone and succeeded in obtaining the surrender of 25 [German officers] and one hundred and twenty men.’ It is an intriguing scenario of which we can only wish we knew more.

This well-crafted and readable book will be of greater interest to family historians than military historians. It attests to the patience and endurance required in genealogical research, as well as the dead-ends and occasional stroke of good fortune that researchers encounter. Probert’s measured self-reflection reminds us that family history carries risk, in that you don’t know what you will find. She and her brothers struggled in their different ways to reconcile the Roy she unearthed with the father Bill they experienced. But Probert also found unexpected rewards in ‘digging up’ a parent. It would be a spoiler to reveal what the greatest of these was: it is saved by Probert for the Coda.

Comments powered by CComment