- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Religion

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Barefoot in the snow

- Article Subtitle: Of poetics and papacy

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The celebrity ghost-written memoir is the non-fiction form de nos jours. Publishers see it as a winner that combines quality narrative with mass-market appeal. Such memoirs do not even need to contain fresh insight when there is an established fanbase. Just ask Prince Harry about the trouble it causes when a revelation does shock. The idea that a pope should put his name to a co-developed text is nevertheless novel. Of Pope Francis’s predecessors, only that preening Renaissance man of letters Pius II Piccolomini contributed to the genre directly. Piccolomini’s Commentaries, though light-hearted Latin, are also a self-indulgent, self-justifying piece of self-invention. The precedent for Francis does not encourage.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Miles Pattenden reviews ‘Hope: The autobiography’ by Pope Francis and translated from the Italian by Richard Dixon

- Book 1 Title: Hope

- Book 1 Subtitle: The autobiography

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $36.99 pb, 310 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780241767160/hope-the-autobiography--2025--9780241767160#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Hope is not a conventional autobiography in terms of content. The title recalls that earlier tome by Barack Obama (The Audacity of Hope, 2006). However, the content lacks that president’s guile or savvy. Early chapters fixate on the young Jorge Bergoglio’s essential italianità (an ancient requirement for an aspirant and popular pontiff). They also reveal the providential nature of his election. His grandparents might have boarded the SS Principessa Mafalda, which sank off the Brazilian coast in 1927, killing a quarter of the passengers. So far, so Piccolomini. The story is not quite as engaging as that pope’s account of the dangers of travelling on the Scots border (local women offered themselves to him, but he was too frightened of dying unabsolved to take them up on it). Francis nevertheless conveys a rather touching sense of the difficulties of the immigrant experience in early twentieth-century Argentina. Life was tough for his parents and grandparents. Their fortitude forged his attitudes. Family and community solidarity are necessary for making a success of life in a new place.

Alas, what might have been a charming, endearing tale that helped us to understand the pathology of a remarkable man descends quickly into moralising. Francis has been very keen on defending the rights as well as dignity of migrants against what he sees as the intolerance and oppression of heartless regimes. Fine. But the assertion that immigrants always need embracing is not self-evidently true. One man’s immigrant is another’s invader. This has been as true in Argentina as elsewhere. Just remember General Julio Argentino Roca’s campaigns against the indigenous people of the Pampas and Patagonia in the 1870s and 1880s (a brutal process of colonisation now known as the Conquest of the Desert).

How does the pope answer critics who worry that immigration to Europe is happening too fast for social systems and cultural solidarities to cope? Few will actually be persuaded by his argument from authority: we must embrace the poor arriving on our shores simply because Christ himself said so. A more cerebral pontiff might have anticipated objections with a rigorous defence of his position, but that is not Francis’s way. Time and again in this book the bland platitude is his handmaiden. He rails against those who build walls: ‘Only those who build bridges can move forward: The builders of walls end up imprisoned by the walls they themselves have built.’ He also teaches via an allegory of football: ‘everyone together to chase and control the ball: It doesn’t matter what your name is, who your family is, where you come from. This will always be the real beauty of the game.’

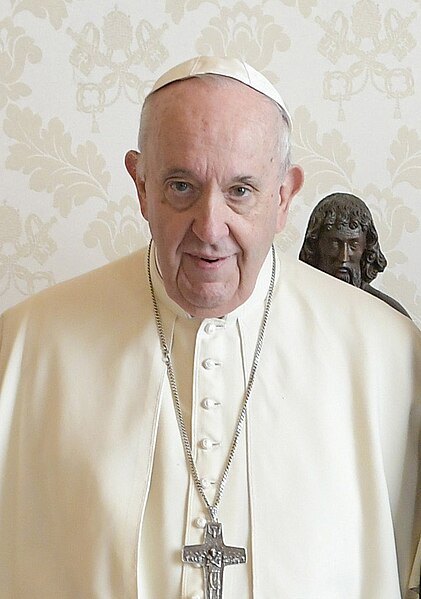

Pope Francis, 2021 (Quirinale via Wikimedia Commons)

Pope Francis, 2021 (Quirinale via Wikimedia Commons)

A note from Carlo Musso, the journalist who is the pope’s co-author, confesses that Francis had originally intended this manuscript to be published after his death. That might have been better for Francis’s reputation. The simplistic nature of his positions grates too often. He endlessly, a fan would say tirelessly, advocates for peace. Yet he seems entirely unaware of – a critic would say, is uninterested in – how peace is achieved. This not only betrays the poor and dispossessed in the present – they are rarely helped by a facile do-gooder scolding everyone into just getting along – but also ignores the great intellectual traditions of Catholicism. Thomas Aquinas, for instance, recognised and expounded on the key concept of ‘just war’. Sometimes you have to fight in order to make peace.

Francis’s pontificating on immigration and war as ‘two sides of the same coin’ irks just as badly. Many today contend that ‘the greatest producer of migrants’ is not war, as Francis supposes, but the desire for economic advancement. Francis has little to say about this.

He tells all kinds of tear-jerker stories, which may or may not be representative. They do not contribute much to meaningful answers to the problems he wants us to confront. One longs for the intellectualism of Benedict XVI, who was often wrong and was sometimes so clever that he sounded dumb. Yet Benedict’s works were usually an engaging read. Hope, not helped here by a mediocre translation by Richard Dixon, nor by the odd, stitched-together nature of the chapters (the product of interviews rather than a considered structure), is not.

Francis is a pope who has drunk deep of the progressive Kool Aid, and this is beginning to cause problems in the Catholic Communion. Witness his recent sharp rebuke of American Vice President J.D. Vance. Vance and Francis clearly disagree on the ordo amoris: the order of responsibility which Catholics bear to their fellow men. The problem is that biblical texts and the Catholic intellectual tradition provide resources to support both men’s positions. By criticising Vance so publicly, Francis rejects this obvious ambiguity. He also puts US Catholics in a bind: they must choose between their politics and their conscience. Modern popes have shied away from such confrontations, because it is not clear that they gain credibility, or followers, from them. Only Francis thinks he knows better. The medieval is his lodestar, as it is in so many other areas of his leadership. But I cannot see Vance, or Donald Trump, walking barefoot through the snow to seek his forgiveness (as the emperor Henry IV famously did for Pope Gregory VII at Canossa in 1077).

The pope might, in fact, do better to look back to Piccolomini’s later medieval example. Piccolomini’s brilliant rhetoric got him nowhere and he died preaching crusade to those who took little interest in his message. Francis’s memoir tells us much about the ego of a man who happens to be pope but surprisingly little about how the papacy can really contribute to solving the world’s problems. The best popes of our era – Leo XIII, Pius XI, John Paul II – have been able to read public opinion and anticipate what will be seen as just and moral in the future. Francis lacks the self-awareness to do this.

It is a pity because there are cultural references in this book that genuinely surprise. A pope quoting Pier Paolo Pasolini, for instance, and waxing lyrical about Dostoevsky, ought to be interesting. Yet rather too much of the book, especially its later chapters, which deal with Francis’s election and travels, is merely a paean to his own virtue. He is kind, he is human, he is humble. We learn surprisingly little about the man behind the mask, not least because most of Bergoglio’s adult life, the formative period of his ministry, is skipped over quickly. In a sense, Francis reflects the shortcomings of Western societies in the present moment: too much feeling at the expense of intellectual rigour and common sense.

Comments powered by CComment