- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Chins up

- Article Subtitle: The pursuit of April Ashley

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

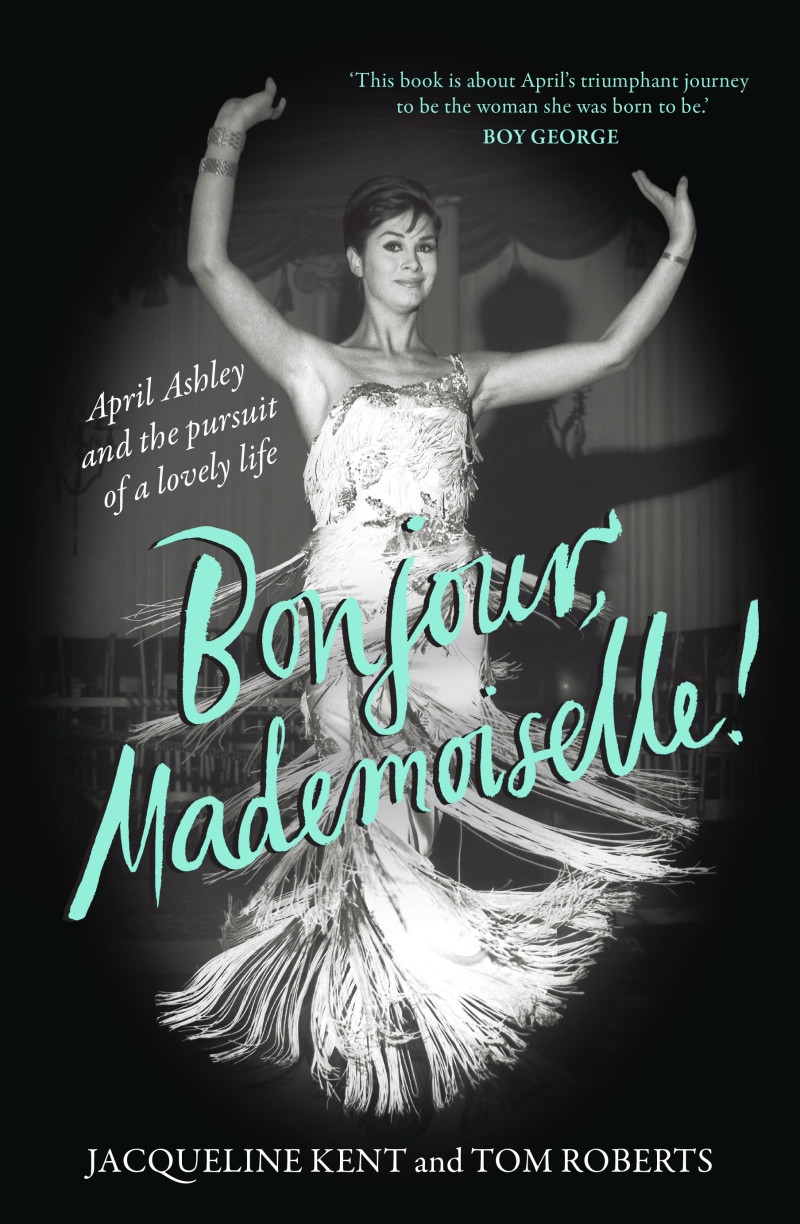

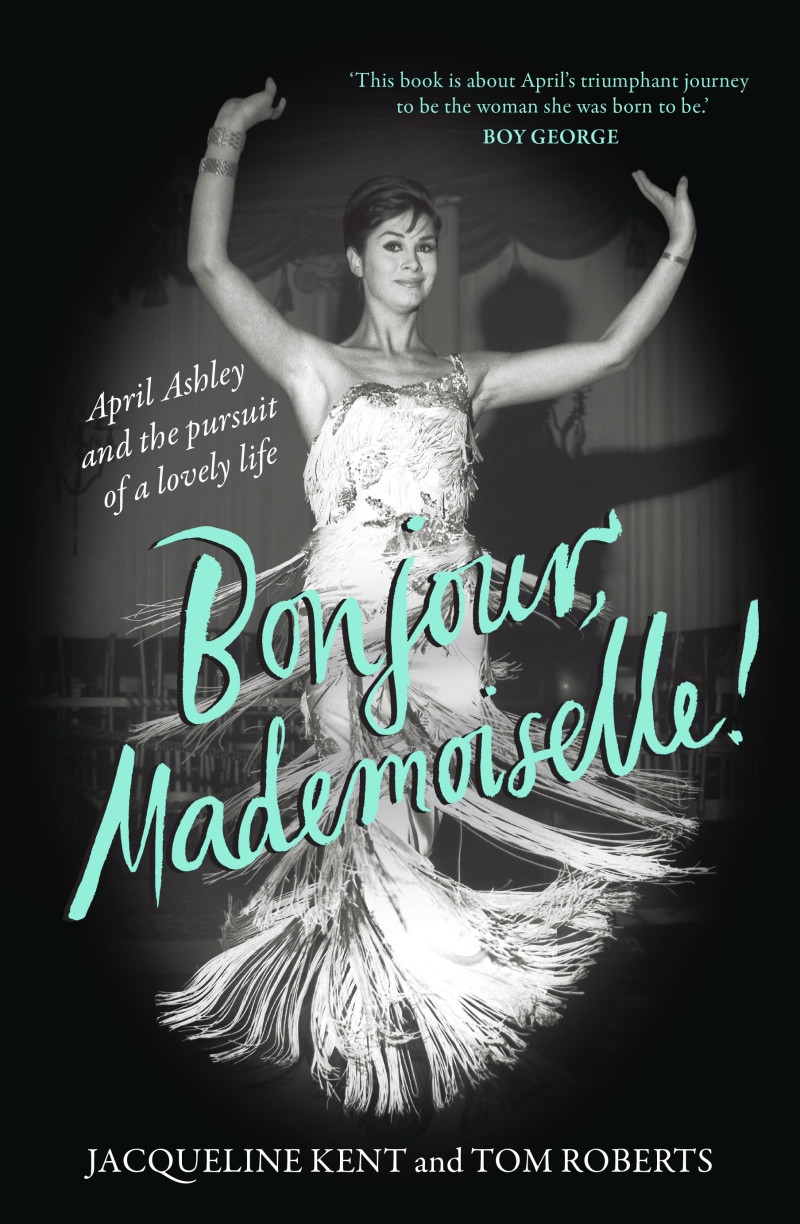

At a time when President Donald Trump seeks to extinguish the legal recognition of trans and gender diverse people, Bonjour, Mademoiselle! and the life of April Ashley feel unexpectedly topical. Ashley, best known in Australia for her role in Corbett v Corbett, a precedent-setting divorce case that set back the legal right of trans people for generations, is the subject of a new biography by Jacqueline Kent and Tom Roberts.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sam Elkin reviews ‘Bonjour, Mademoiselle!: April Ashley and the pursuit of a lovely life’ by Jacqueline Kent and Tom Roberts

- Book 1 Title: Bonjour, Mademoiselle!

- Book 1 Subtitle: April Ashley and the pursuit of a lovely life

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $36.99 hb, 312 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761380310/bonjour-mademoiselle--tom-roberts-jacqueline-kent--2024--9781761380310#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

In this veritable rags to riches story, Ashely was born in 1935 and grew up in a tough, working-class Liverpool council housing estate. Bullied by her siblings and classmates for being a ‘sissy’, Ashley began working at the age of six, delivering newspapers and groceries, before joining the merchant navy at eighteen. After being persecuted by her fellow sailors, she attempted suicide twice before being sent to a psychiatric unit. There her disclosures of her feminine gender identity were interpreted as the delusions of a homosexual male who was unable to accept himself. After electroconvulsive and aversion therapy, Ashley escaped to Paris, where she became a much-lauded drag performer at the famous Le Carrousel nightclub.

‘Bonjour, mademoiselle’ were the first words Ashley heard on waking in a Casablanca hospital bed after gender-affirming surgery in 1960. Perhaps apocryphal, it was a story she told repeatedly over the course of her long life as a model, socialite and reluctant trans trailblazer. Of the fifty per cent survival rate for trans women undergoing such procedures at the time, Ashley told journalists, ‘If I couldn’t be a woman, I didn’t want to live.’

In Bonjour, Mademoiselle, award-winning biographer Jacqueline Kent and British historian Tom Roberts outline Ashley’s life back in London as a lingerie model and love interest of several wealthy, influential men, including daredevil aristocrat Lord Willoughby. When a UK tabloid journalist planned to ‘out’ her, Ashley chose to sell her story to News of the World for £10,000 (around $375,000 in today’s money). Her modelling contracts were promptly cancelled and she was ostracised by high society. In stepped the Honourable Arthur Cameron Corbett, son of Lord Rowallan, governor of Tasmania from 1959 to 1963. Corbett was deeply attracted to Ashley, despite strenuous objections from his father. He left his wife and children and the new couple moved to Marbella, Spain, where attitudes (at least towards monied British exiles) were more relaxed.

The relationship was troubled from the start. Where Corbett was devoted to the point of obsessiveness, Ashley was pragmatic. After the failure of her career, marriage to Corbett provided her with considerable wealth, status, and ‘the deference journalists usually gave to the upper classes’. Then there was Corbett’s own gender nonconformity. He enjoyed wearing women’s clothes and adopted ‘feminine’ characteristics: crossing his legs, adopting a high voice, and making ‘coquettish sideways glances’. Ashley did not welcome this behaviour. This is a complex, underexamined aspect of their ultimately tempestuous partnership. There is a richly interwoven, occasionally fraught political history between trans women and ‘crossdressers’ in twentieth century. Contextualising the relationship in this light would have enriched the narrative.

Soon after marrying, the pair separated and Ashley sued for maintenance. In response, Corbett sought to have their marriage annulled on the grounds that Ashley was male. Over seventeen days, in a process that Ashley described as ‘utterly heart-breaking and humiliating’, her body, mind, and life experiences were scrutinised. In his 1970 ruling, the judge determined that biological sex of a person at the time of their birth determined their legal sex, even if they had undergone gender-affirming surgery. This decision, which meant that trans people could no longer have their birth certificates or passports amended to their affirmed gender, became accepted legal precedent in the United Kingdom (and much of the Commonwealth) until the introduction of the Gender Recognition Act (2004).

Despite Ashley’s public humiliation and ensueing poverty, she survived. She lived for decades in the United States and France, eventually returning to London in 2008. In 2012, as trans rights were on the ascendance, she was made an MBE for ‘services to transgender equality’.

Ashley, despite publishing two ghost-written autobiographies and giving dozens of interviews throughout her long life, is not a household name in Australia. Better known in the United Kingdom, she has come to personify the glamour and evolving sexual mores of 1960s London high society. Kent and Roberts have situated April Ashley’s life in its broader political and social context. Thorough and eminently readable, the book strikes an engaging, affectionate tone for their at times poorly behaved and doubtless traumatised subject. With tact and curiosity, the authors examine Ashley’s frosty attitude towards her mother and her possibly unwarranted reverence for her father.

The decision to refer to Ashley prior to her surgery by her male birth name and pronouns will grate with some readers, particularly those from the trans and gender diverse community under fifty. This decision is explained in the Authors’ Note as in keeping with the ‘language with which [Ashley] described her experience’. It is an interesting tension: how best to honour Ashley’s own understanding of her life when contemporary conventions around describing a person’s gender history have changed so much? But Bonjour, Mademoiselle has captured Ashley’s optimistic, courageous approach to life, which Ashley summarised for The Liverpool Daily Post in 2008. ‘I always say three things. Be beautiful, be kind – to yourself and others – and most of all be brave. Chins up – get on with life and be as brave as you can.’

Comments powered by CComment