- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: My unread books

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: My unread books

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reading fiction is an intimate business. For ten, fifteen, twenty hours of glorious solitude, you engage with ideas, events, and, most especially, characters located in periods and places not your own. The connection with fictional characters can sometimes feel more real and enduring than relationships with real people. For a few years in my youth, I was so deeply attached to the young Hurtle Duffield in Patrick White’s The Vivisector that I wrote a short story in which Hurtle and I lived with Patrick White and Virginia Woolf in Bloomsbury.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

%20FEAT.jpg)

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): ‘My unread books’ by Andrea Goldsmith

Some novels stay with you for a lifetime. It’s a permanent relationship, one without the petty arguments, the smelly feet, that irritating jiggle that your beloved has made no attempt to control. These books become part of you; they become my books.

Then there are the books you should have read and have always wanted to read – but haven’t. These are my unread books. Back in 2007, Pierre Bayard published How to Talk about Books You Haven’t Read. Not surprisingly, it was a bestseller. I read this clever, witty book with great enjoyment. But Bayard’s mood of inspired and intelligent levity did not stay with me, and I remained haunted by those books I should have read but haven’t. I’m still haunted – and accused as well.

I came of age in the 1970s. At that time there was a canon of fiction that one should read – the moral imperative was deeply felt. It included Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, Sartre and Beauvoir, Camus and Orwell, James and Wharton, Austen and the Brontës, Lawrence and Huxley, Woolf and Proust, and, of course, Joyce. Given that I preferred reading to sleeping, eating, and socialising, acquiring the canon was a pleasurable and easy task, except for Joyce.

Bloody James Joyce.

I managed the stories collected in Dubliners – I actually enjoyed them, particularly ‘The Dead’ – but I limped through my mother’s stained yellow, cloth-covered copy of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I have just checked that copy, a 1934 ‘flexible’ edition from Jonathan Cape. Stamped on the inside front and back covers are the words ‘The Athenaeum Club’, in old English lettering. How had it come into the possession of my mother? She was not the type to steal books, nor was she a member of The Athenaeum, or, indeed, any other club. My mother, like her daughter, was not the clubbable type. And I am reminded again how books hold so many stories, inside and outside the pages.

Back to Joyce. I first attempted Ulysses at the age of twenty-one. It was a birthday gift from my sister’s boyfriend, who fancied himself an intellectual. I struggled to page 150 before giving up. I have tried to read it several times since. My Penguin modern classics edition runs to 703 pages, my copy falls open at page 252. My failure, measured in 451 pages, is pronounced and bleak.

When I was in my mid-twenties, I happened to be in New York City on Bloomsday. I was staying on the Upper West Side. Just a few blocks away, a twenty-four-hour reading of Ulysses was to occur. I took myself along, hoping that exposure to a performance of this great work would assist me in tackling it on the page. The room was dark and smoky, with a small stage at one end; there was wine and a crush of bodies, and there must have been chairs, though in my mind everyone is standing. What I do recall clearly is the melody of the readers’ voices, that Irish lilt, but the rest is a blur; indeed, it was a blur soon after the event. Were there drugs? Did I drink too much? I can’t be sure, but what I do know for certain is that the experience did not help me read Ulysses.

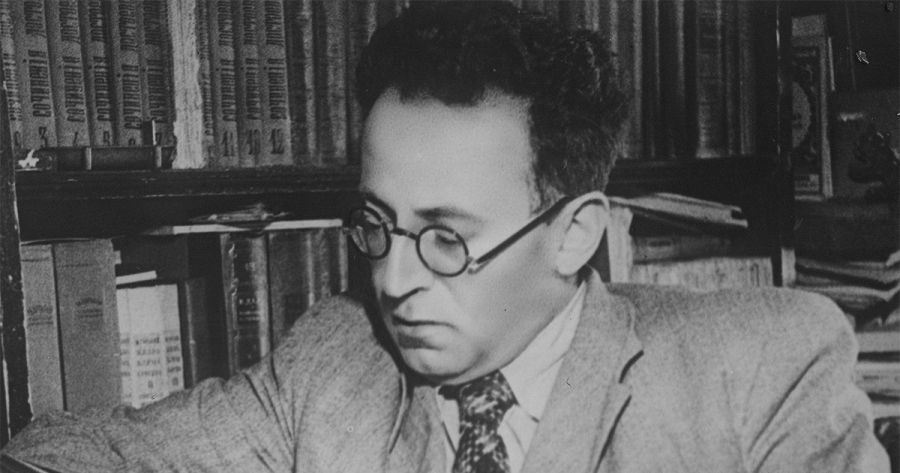

Vasily Grossman at Pushkin House (Album/Alamy)

Vasily Grossman at Pushkin House (Album/Alamy)

Another of my unread books is Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate. While I’ve long been aware of this omission, in recent years it seems that nearly all the non-fiction writers I admire refer to Grossman’s novel. And I am suffering, as I have suffered over Ulysses. I have tried reading Life and Fate three or four times, and with each attempt I have failed.

In my Vintage paperback edition, translated from the Russian by Robert Chandler, Life and Fate is 855 pages. It is a novel with a cast so large that there is a seven-and-a-half-page appendix listing the main characters. My copy falls open at page sixty-two. It’s pathetic: so many attempts and only sixty-two pages read. I have taken it down from the Russian shelf in my library because this morning, over breakfast, I read a chapter devoted to Grossman in Tzvetan Todorov’s Hope and Memory. Todorov is a brilliant political and moral philosopher; I not only admire Todorov, I’m grateful for all he has given me. Todorov is championing Grossman, and I simply cannot, must not ignore this.

I will go to my grave having not finished Ulysses, but even in my failure I am far from ignorant about the book. Indeed, with Bayard as a guide and because Ulysses is part of our cultural capital, I could converse about Ulysses more than adequately. It is quite another matter with Life and Fate, purportedly a great – some, like Todorov, would say the greatest – novel about totalitarianism.

Life and Fate was completed by Grossman in 1960, but even in the Khrushchev thaw, the novel was never going to be published in the Soviet Union. Interestingly, instead of arresting the author, the KGB arrested the book: the copies, the drafts, the notes, the carbon paper, even the typewriter ribbon was banished. Unknown to the KGB, Grossman had made two other copies that he had entrusted to friends. Grossman died in 1964, and sixteen years later, Life and Fate was finally published, in Lausanne, under the title of L’Age d’Homme. Robert Chandler’s English translation appeared in 1985.

In our contemporary era, there are lurchings towards authoritarianism across the globe. While there can be authoritarianism without totalitarianism, all totalitarianisms have authoritarian leaders. Life and Fate, the little I know of it, seems to speak to the times in which we live. Perhaps it is one of those rare novels that speaks to all times. I’m about to find out.

Yes, I am going to start the book again and I will not give up. I cannot give up. I need to read Life and Fate not only to learn more about the felt experience of living under Hitler’s totalitarianism and Stalin’s Soviet version, but perhaps more urgently to make sense of the times in which we now live. This novel calls to me as a citizen in a world that has run amok. This novel must be removed from my list of unread books.

%20RAI.jpg)

Comments powered by CComment