- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: H.D.’s chief confidant

- Article Subtitle: Biography of a groupie

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

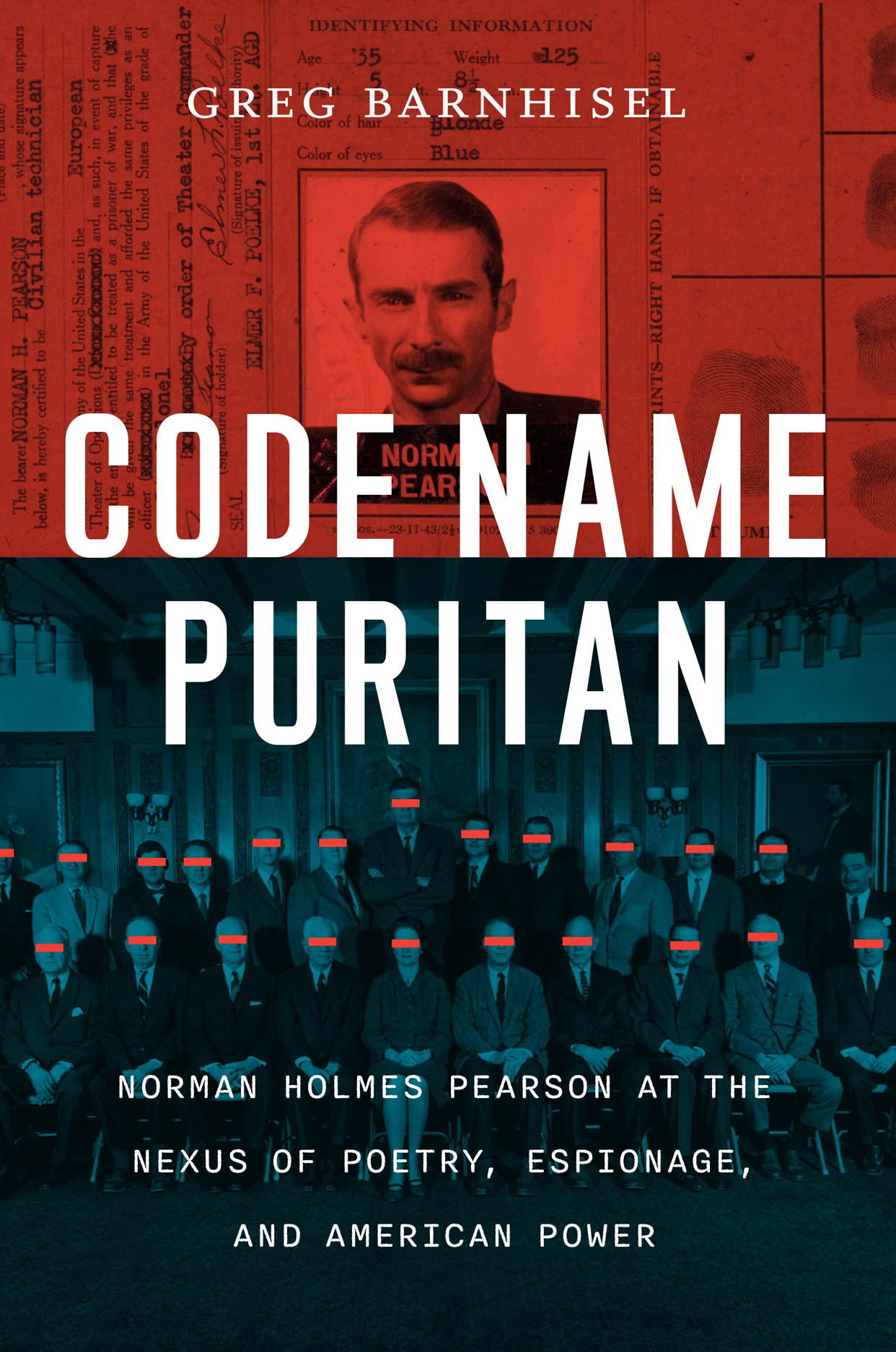

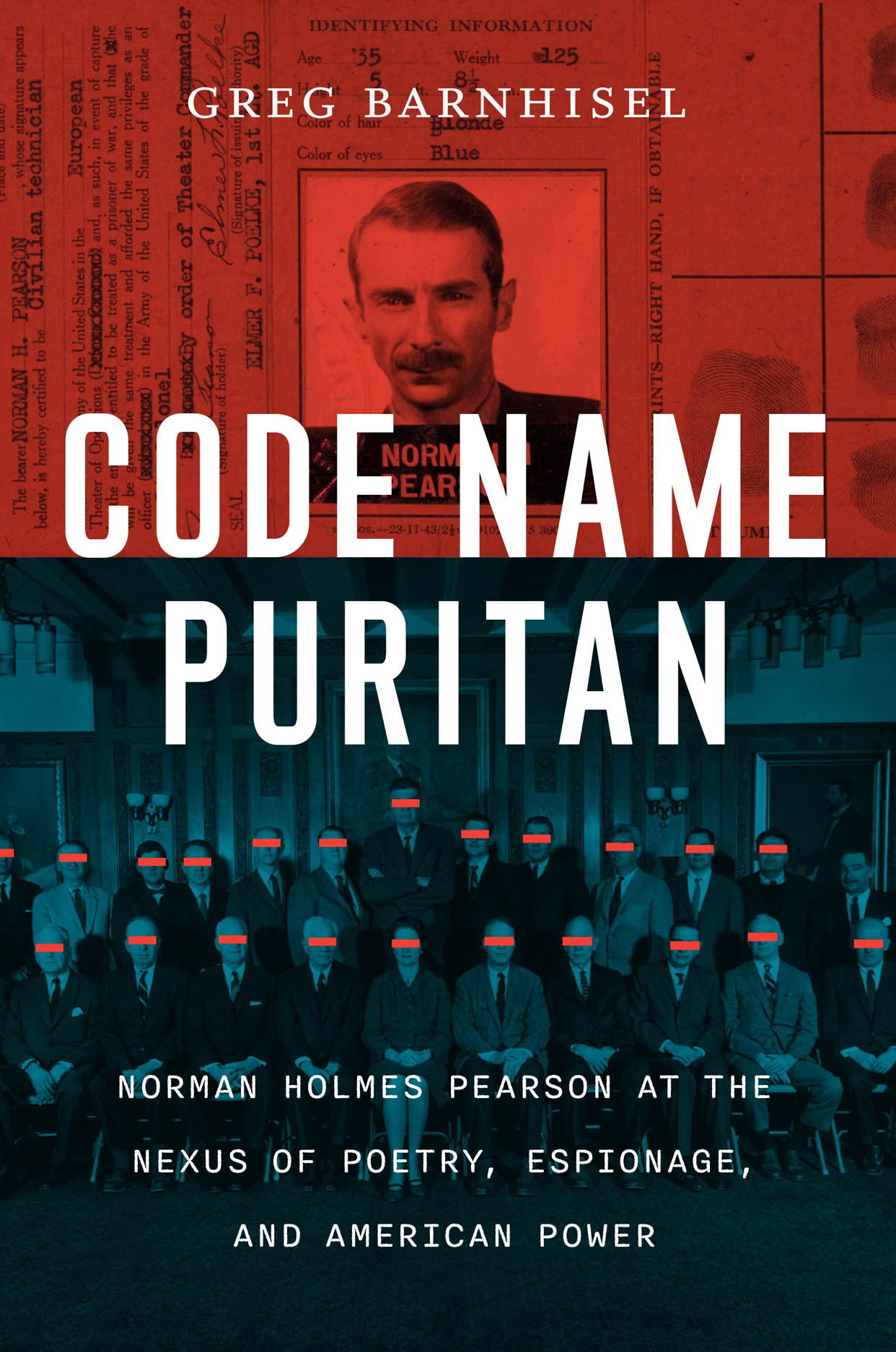

In his brief Foreword to H.D.’s posthumous collection, Hermetic Definition (1974), Yale Professor Norman Holmes Pearson (1909-75) provides an authoritatively crystalline summary of the poet’s life’s work. Asserting the primacy of her later poetry, the ‘war trilogy’ (1942-44) and Helen in Egypt (1961), Pearson recovers H.D. from her accepted but ‘inadequate’ typecasting as an Imagist, identifying her deployment of Freud as ‘a great mythologist’ in her highly personal engagement with hermetic and kabbalistic sources.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): John Hawke reviews ‘Code Name Puritan: Norman Holmes Pearson at the nexus of poetry, espionage, and American power’ by Greg Barnhisel

- Book 1 Title: Code Name Puritan

- Book 1 Subtitle: Norman Holmes Pearson at the nexus of poetry, espionage, and American power

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press, US$32.50 hb, 386 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780226647203/code-name-puritan--greg-barnhisel--2024--9780226647203#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

As Greg Barnhisel’s revealing biography explains, Pearson was an unusually qualified commentator: as H.D.’s chief amanuensis and confidant, he not only assisted in the publication of her later works, but also chose the poems for the Selected Poems (1957), which brought her renewed attention as a central figure in the modernist canon. He then introduced her to the younger poet Robert Duncan, inspiring his major critical work, The H.D. Book (1984); Duncan’s engagement with Hermetic Definition is evident throughout his breakthrough volume, Roots and Branches (1964). But the influence of Pearson’s assistance was not restricted to H.D.: he also chose the poems for William Carlos Williams’s New Directions Selected Poems (1949), and was one of only four mourners from the literary world to attend Wallace Stevens’s business-oriented funeral.

It is unusual for a biographer to suggest that the following terms might apply to his subject: ‘a sycophant, a groupie, a name-dropper, a suck-up, a hanger-on’. Barnhisel’s ambivalence, in part political, is apparent throughout his study, but he also provides the reader with evidence for a more sympathetic impression. Pearson’s lifelong advocacy for modernism was sparked by Mark van Doren’s 1928 Anthology of World Poetry (also where Kenneth Slessor encountered key US modernists Ezra Pound, Williams, and H.D.); he was further ‘modernised’ by Gertrude Stein’s celebrity lecture tour of 1934-35. As the young editor of the Oxford Anthology of American Literature (1938), Pearson was responsible for placing experimental poetry firmly at the centre of the newly emerging field of American Studies. With his appointment in 1947 as the foundational undergraduate director of the Yale American Studies program, he would play a key role in shaping the discipline. This included the first university class devoted to the study of Ezra Pound’s The Cantos, eliciting some of the earliest scholarship on the poet, at a time when Pound was at his most controversial. Pearson’s students included future New Journalist Tom Wolfe, who responded with a 105-page analysis of ‘Canto 47’.

As Barnhisel rather pejoratively notes, Pearson produced no major publications of his own, preferring instead to cultivate direct relationships with the leading American writers of his time through a busy correspondence. This approach was quite contrary to the prevailing New Critical academic orthodoxy of the postwar years, in which authors were subsumed beneath ‘intentional fallacy’, and the sprawling collage epics of modernism (such as The Cantos and Williams’s Paterson) were ignored by a criticism which preferred the closed model of the poem as ‘well-wrought urn’. Pearson was equally out of place in the subsequent wave of Yale Deconstructionism, which mainly adopted a studious blindness to the explosion in experimental American literature burgeoning beyond the campus. Pearson, by contrast, was quick to pick up on developments in the San Francisco underground of the late-1950s, forming links with Duncan and Gary Snyder. Most remarkably, he provided personal funding for Ed Sanders’ seminal countercultural journal, Fuck You/A Magazine of the Arts (1962-65), with Sanders explaining to his readers that the journal was sponsored ‘by a leading Ezra Pound scholar at Yale’.

The political dimension of Barnhisel’s study focuses on Pearson’s wartime recruitment, along with other leading humanities scholars, as a spy for the Office for Strategic Services. This was not in itself unusual: Graham Greene was among the fellow spies Pearson encountered in London, and the biography of his contemporary, the Poundian poet Basil Bunting, remains suspiciously mysterious. The implication is that Pearson retained his CIA connections through the postwar period, though there is little evidence that he was involved in recruitment. Barnhisel connects this with the Cold War cultural diplomacy of the United States (sponsored by the Rockefeller, Ford, and Carnegie foundations), with American Studies programs deployed to ‘put a positive face on American civilization to generate goodwill for US policies among intellectuals and opinion makers’.

As American cultural ambassador to the Pacific, Pearson made two trips to Australia, in 1968 and 1970, to advance the Cold War cause in literary studies. Viewed from an Australian perspective, these visits seem to have been entirely ineffectual – especially compared with the influence of US critic Clement Greenberg on Australian artists: 1968 was the year of the notorious Field Exhibition, which virtually extirpated the Antipodean School in favour of American models.

By the time of Pearson’s visit, younger Australian poets had already absorbed the new American poetry through Donald Allen’s 1960 Grove Press anthology. Barnhisel seems unaware of a more direct CIA involvement in Australian literature: the funding of the Australian Association for Cultural Freedom to assist in the production of Quadrant.

Comments powered by CComment