- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Paris, Harlem

- Article Subtitle: In search of James Baldwin

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Colm Tóibín has that special distinction among contemporary writers of being both a first-rate novelist and an acutely discerning critic. In recent years, as well as publishing some magnificent novels, among them Brooklyn (2009), Nora Webster (2014), and Long Island (2024), he has written searching critical studies of other writers, including Elizabeth Bishop (2015). His latest critical work, On James Baldwin, was published in 2024 to coincide with the centenary of Baldwin’s birth. It grew out of the Mandel Lectures in the Humanities that Tóibín delivered at Brandeis University, but it also draws on a long and passionate engagement with Baldwin’s work, including an essay on Baldwin and Barack Obama published in the New York Review of Books in 2008.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Stephen Regan reviews ‘On James Baldwin’ by Colm Tóibín

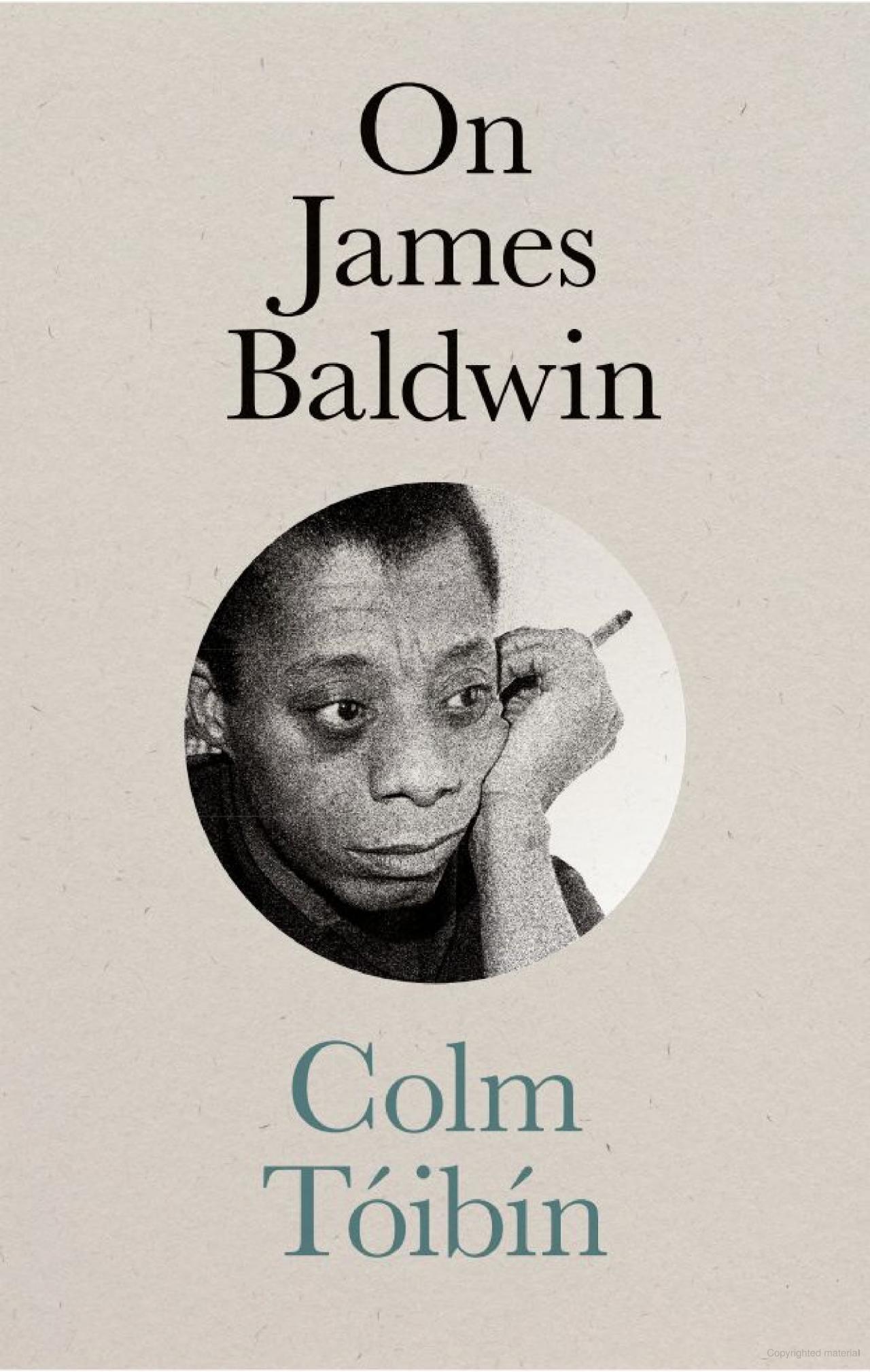

- Book 1 Title: On James Baldwin

- Book 1 Biblio: Brandeis University Press US$19.95 hb, 147 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781684582471/on-james-baldwin--colm-toibin--2024--9781684582471#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

On James Baldwin opens not, as might be expected, in Harlem, but in Dublin. In a confiding autobiographical prose that has become a hallmark of his criticism, Tóibín recounts how his reading of Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), coincided with the end of his Catholic schooling in Ireland and his first year of university study. Having served as an altar boy in Enniscorthy Cathedral, he was alert in his reading of Baldwin to ‘the way in which the heightened emotion around ritual and religious belief strayed into same-sex desire’. He had encountered complex feelings to do with conscience and sin in his reading of James Joyce, of course. It must have been highly satisfying for him, then, to discover that Baldwin had read Joyce in 1950, while working on his novel, and that in Paris he had felt sustained by the artistic ideals of ‘silence, exile and cunning’ in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). Baldwin also acquired from his reading of Joyce a readiness to experiment with different and competing styles, which Tóibín regards as a fundamental and persistent feature of the African American writer’s work.

In Baldwin’s novels, perhaps most obviously in Go Tell It on the Mountain, the language of hymns and prayers and sermons vies with the language of the Western literary tradition. Tóibín notes with approval how Baldwin ‘will not settle for a single style’. He goes on to show how a ‘plain, placid style’, akin to that of a folk tale or a psalm, can co-exist in his fiction with a ‘bravura style’ inspired by Charles Dickens. There is also in Baldwin’s writing an especially eloquent style that Tóibín associates with the operations of the mind and the search for truth. The influence this time derives from Henry James, another of Tóibín’s own great literary progenitors. Baldwin, he claims, ‘carried in his temperament a sense of Henry James’s interest in consciousness as shifting and unconfined, hidden and secretive, and he shared James’s concern with language as both pure revelation and mask’.

Some of Baldwin’s contemporaries were disapproving of what they saw as an overly flamboyant style. Ralph Ellison, author of Invisible Man (1952), who was among the first readers of Go Tell It on the Mountain, objected to the ‘Jamesian prose’ of the book and complained in a letter to a friend, ‘As for Baldwin, he doesn’t know the difference between getting religion and going homo.’ Tóibín shows admirable discretion as he recounts Baldwin’s sometimes difficult relationships with other Black writers, such as Richard Wright, and with fellow members of the civil rights movement who were apt to slight him for his sexuality. He also shows great critical adventurousness in his reading of Baldwin’s first novel, sensitively exploring the principal themes of religious conversion and self-realisation, and revealing how the displacement caused by the Great Migration from South to North shapes the inner life and the social relationships of Baldwin’s characters.

Geographical displacement was also the catalyst for Baldwin’s second novel, Giovanni’s Room (1956), set in Paris. Tóibín writes superbly well about the Harlem-Paris axis, about the ambiguous freedom of African American writers and musicians in a cosmopolitan European city, and about the extent to which the city prompts heightened thoughts and feelings to do with sexuality, both proposing liberation and inducing panic and emptiness. He finds the genesis of Giovanni’s Room in Baldwin’s short story ‘The Outing’ (1951), his first dramatisation of homoerotic desire, but he also connects it to a tradition of American novels set in Paris, including The Ambassadors by Henry James, about which he writes with brilliant insight. Above all, though, he sees Giovanni’s Room as a novel characterised by the complicated confessional rhetoric of its narrator, David. Once again, the book is lifted by Tóibín’s personal narrative, as he embarks on his own confessional recounting of ‘the silence, the invisibility, the strangeness’ of being a gay man on the streets of Barcelona in the years that he lived there. A powerful comparison is drawn between Baldwin’s technique and Oscar Wilde’s confessional style in his prison letter, De Profundis (written in 1897), with both the novel and the letter possessing ‘a beautiful calm eloquence in the writing’ as well as a ‘a sense of urgency, of matters newly realized’. ‘All art is a kind of confession, more or less oblique,’ Baldwin memorably declared.

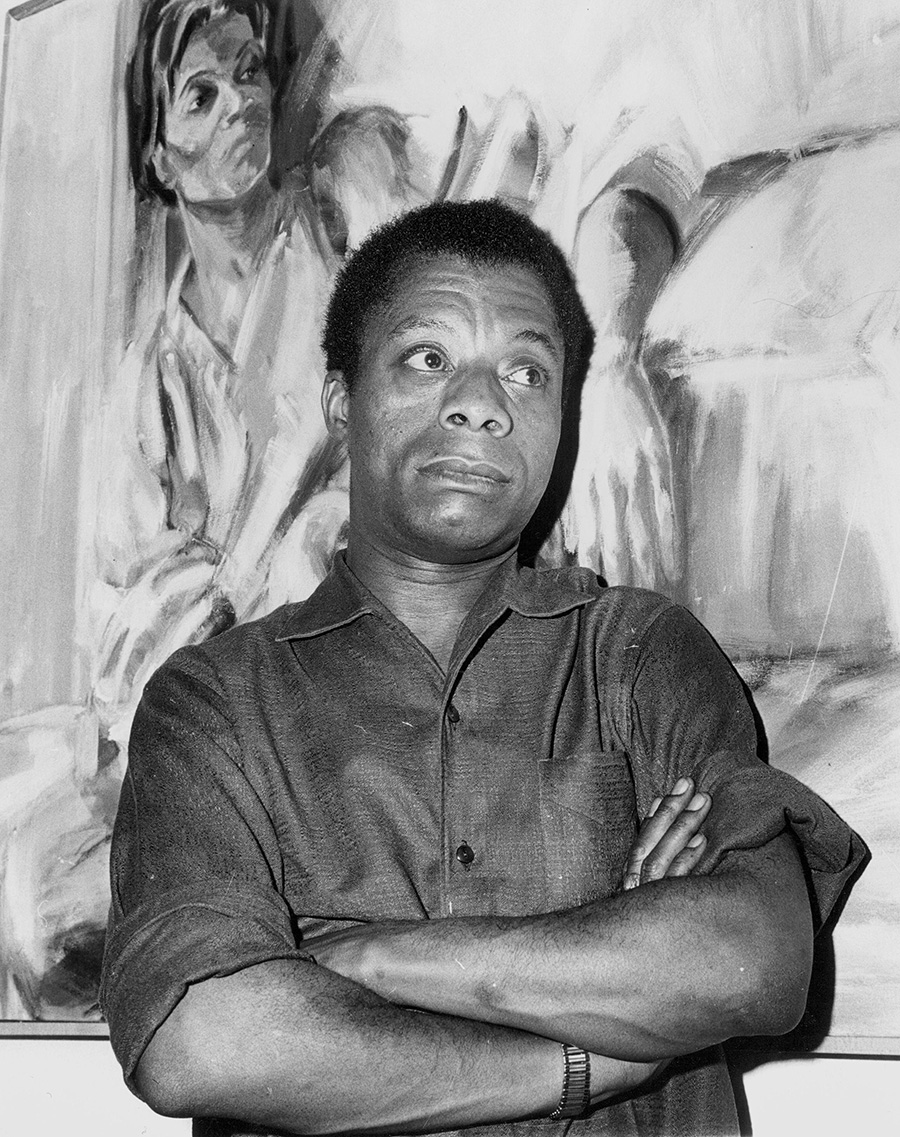

James Baldwin (Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy)

James Baldwin (Granger Historical Picture Archive/Alamy)

As Tóibín notes, Baldwin’s reputation as a novelist and essayist rests mainly on the work he produced between 1953 and 1963. In that period, he published the three volumes of essays that would give him a powerful public presence in American political life: Notes of a Native Son (1955), Nobody Knows My Name (1961), and The Fire Next Time (1963). Tóibín greatly admires Baldwin’s non-fictional writings, especially the two long pieces that constitute the 1963 volume: ‘The essays are personal and passionate and angry. The tone can also be wise, analytical, knowing, clued-in and ironic, relishing nuance, ambiguity and paradox.’ He offers some sharp insights into Baldwin’s television interviews and occasional journalism, including a little-known piece on boxing, prompted by the fight between Floyd Patterson and Sonny Liston for the undisputed heavyweight championship in 1962. In the process, Tóibín lands a swift uppercut on Norman Mailer, whose ideas about men and masculinity were very different from those of Baldwin, and knocks him out with a single sentence: ‘The worst writer about boxing was Norman Mailer.’

Mailer had complained that Baldwin’s novel Another Country (1962) was ‘abominably written’, and Tóibín spends the final pages of his study on an impassioned defence. As he contemplates the fate of Rufus, the young musician from Harlem who dares to live in Greenwich Village, he dwells on the connecting cityscape of Riverside Drive, where Tóibín himself is living at the time. The George Washington Bridge looms overhead, linking him to the novel. In a poignant interlude, he turns on himself with a humbling self-critique, wondering what Baldwin might make of his literary musings: ‘I can’t imagine the scorn he would pour on some Irishman sitting helplessly in some apartment on Riverside Drive …’ What comes across most clearly in this marvellously engaging short book, however, is Tóibín’s indubitable sense of writerly solidarity and his readiness to admit his own vulnerability, as Baldwin bravely did. The book closes abruptly, but fittingly, with Baldwin dreaming of ‘a region where there were no definitions of any kind, neither of color nor of male or female’.

Comments powered by CComment