- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Your body, my chow’

- Article Subtitle: Two novels about female appetite

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

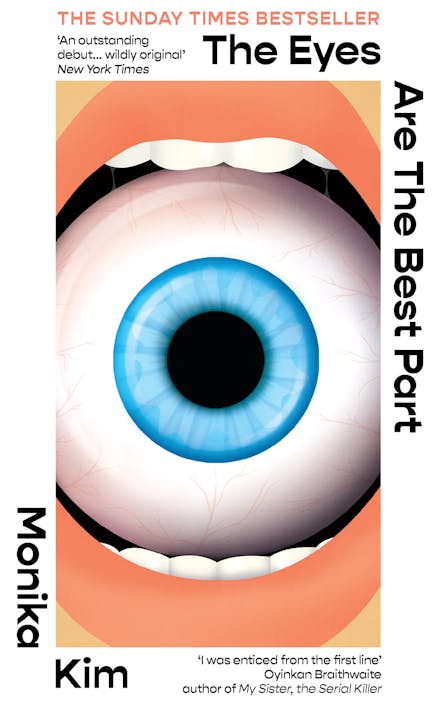

In 2018, the Oxford English Dictionary added the word ‘hangry’, defined as ‘bad-tempered or irritable as a result of hunger’. Incidentally, the word ‘mansplain’ was also added in 2018. If you are not familiar with this one, I am sure there is a man nearby who will be happy to enlighten you. Reading Monika Kim’s début novel, The Eyes Are the Best Part, I began to wonder whether we may now need a word to describe the inverse state of being ‘hungry as a result of being bad-tempered or irritable’. Some onomatopoeic portmanteau of ‘rage’ and ‘ravening’, perhaps?

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

%20by%20Marina%20Yuszczuk%20-%20FEAT.jpg)

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Eleanor Spencer-Regan reviews ‘The Eyes Are the Best Part’ by Monika Kim and ‘Thirst’ by Marina Yuszczuk

- Book 1 Title: The Eyes Are the Best Part

- Book 1 Biblio: Brazen, $34.99 pb, 289 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781840918397/the-eyes-are-the-best-part--monika-kim--2024--9781840918397#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

- Book 2 Title: Thirst

- Book 2 Biblio: Scribe, $29.99 pb, 256 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

%20by%20Marina%20Yuszczuk.jpg)

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

%20by%20Marina%20Yuszczuk.jpg)

- Book 2 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780593472088/thirst--marina-yuszczuk--2025--9780593472088#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Kim’s protagonist, Korean-American eldest daughter Ji-won, has a lot to be bad tempered about. Her Appa has left the family’s apartment after an extramarital affair, her Umma is feverishly cooking traditional Korean dishes in the vain hope of luring him home, and she is daily subjected to racist and misogynistic micro-aggressions by the frat boys on campus: ‘Once you go Asian, you never go Caucasian.’

Both George, her Umma’s new boyfriend, and Geoffrey, her performatively woke classmate, are veritable semaphore displays of red flags. George is a middle-aged white man who shamelessly ogles young waitresses and drives a truck decorated with GOP bumper stickers. His loudly self-professed appreciation of ‘Asian’ culture begins and ends with Kung Pao chicken and Lolicon pornography.

The eyes that constantly stray to Ji-won’s breasts are ‘a pale, icy blue that reminds [her] of the Niagara Falls’. Soon she begins to dream vividly about eating these eyes: ‘My hand darts out and snatches the eye from the plate, and before I can think, I shove the entire thing into my mouth. The cartilage is thick and tough. I bite down until it pops, bursting open, its salty liquid oozing down my throat.’ This is no more an act of violence than George’s self-satisfied butchering of her family’s mother tongue, his lascivious visual dissection of Asian female bodies, and his unwillingness to pronounce the sisters’ names correctly (‘pronunciation isn’t my strong suit. If it bothers you that much, I can give you both nicknames’).

Admittedly, it is hardly a subtle metaphor, especially to any reader familiar with John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972) or Laura Mulvey’s ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ (1975). It is the unremittingly toxic masculinity of every man in this novel that is the true source of horror, rather than the gruesome appetites of the protagonist, perhaps because, as with Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991), we begin to question the reliability of our ‘unravelling’ first-person narrator. The too-frequent dream sequences and the sudden, almost offhand neurological diagnosis at the end of the novel leave the reader in doubt as to whether the whole thing was a murder spree or merely an impotent feminist revenge fantasy.

That said, it is the uneven pacing rather than the premise of Kim’s novel that sticks in the throat. The entirely predictable climax of the novel feels strangely perfunctory, especially compared to the somewhat sluggish earlier chapters, and Ji-won’s parting vow (a little patricide is on the menu) feels strangely bloodless.

It is not hunger but thirst that drives the vampiric protagonist of Marina Yuszczuk’s novel Thirst, originally published in Spanish as La Sed (2020). Comprising two converging first-person narratives, it is set in Buenos Aires in the late nineteenth century and the years immediately post-Covid. The novel has been described as a ‘queer vampire novel’, but, given the inherent queerness of the genre since the days of John William Polidori, this seems almost tautological.

With her cadaverous pallor, ‘Maria’ initially seems more akin to Max Schreck’s Nosferatu than Stephanie Meyer’s sparklingly sanitary and well-socialised Cullen clan. In fact, Yuszczuk draws on a wide range of source texts. Her vampire is variously a Gothic seductress who calls to mind Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla; the kind of tortured soul familiar to readers of Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire; a vigilante in sunglasses reminiscent of Blade; and an almost moral monster who bemoans her own violent existence in the mode of the creature in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

The humanised or feeling vampire is hardly new. Despite her superhuman strength, it is Maria’s vulnerabilities that allow the reader to identify with her. Sold by her starving mother to a shadowy ‘Master’ in a high castle, she recalls that ‘there were many other like me, little girls and boys held captive in freezing rooms, steeped in our own filth; we would occasionally be thrown scraps of food to keep us alive’. Such inhumane treatment leads her to grow up ‘mad with fear and suppressed rage’, and we readily understand that she is more sinned against than sinning, even as she drains a young priest of his blood in a makeshift black mass.

If Maria’s orgiastic feeding on the city’s underclass holds a mirror to the violence and danger of life in late nineteenth-century Buenos Aires, it is societal anomie and personal ennui that we see reflected in the modern-day Alma’s numbed alienation, not only from those around her but from her own once urgent needs and desires. The vampire thirsts for blood, but Alma, recently divorced and struggling to comprehend her mother’s terminal illness, has lost her appetite for life. While it is Maria who is inadvertently freed from her coffin, it is Alma who is truly awakened by their encounter.

The historical portion of the narrative is more successful than that set in the present. Alma reflects, ‘[Maria] doesn’t seem to belong … how can I explain it … in this reality’. Indeed, Yuszczuk’s vampire seems to be stripped of all allure in a Buenos Aires of neon signs and overpriced wine bars. Moments that were surely intended to evoke pathos – for example, when the centuries-old vampire walks blithely into traffic (‘I explained how traffic lights worked and realised I was going to have to explain everything to her: traffic, cars, the city as it was now’) – seem instead mildly comic.

Yuszczuk’s prose style is to tell rather than show, particularly in this second half of the novel where her narrative signposting becomes entirely superfluous. The reader could probably intuit without the author’s help that, having descended into the family crypt and unlocked a coffin, Alma has lived ‘her last day in a familiar world’.

Despite the graphic descriptions of murder and sex throughout the novel, it is Alma’s decision to desert her young son and join Maria in the mausoleum (thus bookending the narratives with a pair of abandoned children) that arouses the most visceral reaction. This perhaps reveals a set of traditionalist assumptions about the sanctity of motherhood, but it is also because the decision is not so much a delicious plot twist as entirely unsupported by the narrative thus far. That a young woman should be in thrall to a vampire is an accepted generic convention, yet Yuszczuk fails entirely to flesh out Alma’s sudden but powerful obsession with Maria, suggesting neither a supernatural influence at work nor the unhinging effects of grief. As T.S. Eliot might say, there is no objective correlative, and it leaves the reader feeling unsatisfied, despite the seeming richness of the fare.

Despite their weaknesses, both novels speak powerfully to the fact that women have appetites, and not just those that can be suppressed with Ozempic. In a post- and now also pre-Trump age, the continuing assaults, both physical and political, on female bodies and freedoms will lead authors like Kim and Yuszczuk to create imaginative spaces in which women can defend themselves. While men like Nick Fuentes crow ‘your body, my choice’, we need protagonists like Ji-won and Maria who will sharpen their knives, lick their lips, and retort with ‘your body, my chow’.

Comments powered by CComment