- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Patriarchal horror

- Article Subtitle: A bizarre curio from the Nobel laureate

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

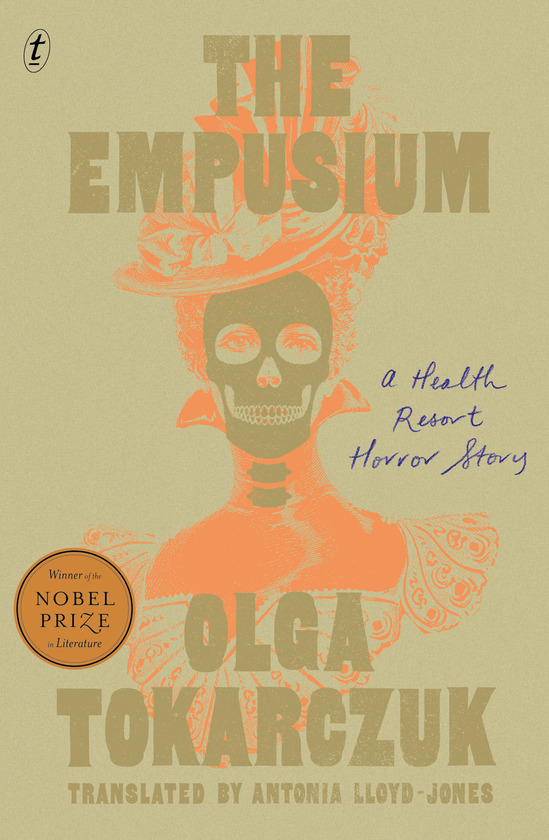

The title of The Empusium, the newly translated work by Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, is an invention. It is a portmanteau that fuses masculine and feminine literary allusions: first, Plato’s Symposium, which tells of a drunken Athenian banquet in which great statesmen give speeches on the nature of love; second, the empusa, a shape-shifting female demon who, according to Greek mythology, had the sirenic ability to lure and prey upon young men.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jonathan Ricketson reviews ‘The Empusium: A health report horror story’ by Olga Tokarczuk

- Book 1 Title: The Empusium

- Book 1 Subtitle: A health report horror story

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $34.99 pb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780593712948/the-empusium--olga-tokarczuk--2024--9780593712948#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Like its concocted title, The Empusium is a bizarre curio, a strange and uncategorisable novel that melds disparate elements into a satisfying whole. The set-up is a riff on Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (1924): it follows an engineering student, Mieczyslaw Wojnicz, who, in 1913, seeks treatment for tuberculosis at an expensive sanatorium in Görbersdorf (now Sokołowsko) in Western Poland. A traumatised young man, Wojnicz hopes that the clear mountain air and the tortuous bathing regimes will cure his affliction. He enters a gentleman’s guesthouse, filled with pompous pseudo-intellectuals who can be difficult to distinguish from one another: Walter Frommer (‘theosophist’ and ‘privy counsellor’), August August (‘socialist-humanist’ and ‘classical philologist’), and Longin Lukas (‘Catholic traditionalist’ and ‘gymnasium teacher’). Wojnicz sees a kindred spirit in Thilo von Hahn, a sensitive young painter who is dying. A large part of the novel consists of dull and vexatious conversations between the men in the guesthouse. The topics traverse art, philosophy, science, and religion. As Wojnicz listens, he notes that the subject always returns to their negative perceptions of women. The vile Longin Lukas, opining on symbolism in Renaissance art, argues that the Mona Lisa’s smile represents ‘a woman’s entire evolutionary strategy for coping with life [which] is to seduce and manipulate’.

To construct these discussions, Tokarczuk has ventriloquised the misogynistic views of important writers of the past (in her Author’s Note, she states that she drew upon Freud, Darwin, Shakespeare, Sartre, Ovid, Swift, and Plato, among others). That the modern reader finds them alienating and abhorrent is part of Tokarczuk’s design; she wants to startle the reader, to brutalise them with the reality of misogyny that is all-pervasive as the respiratory illness that permeates the mountain resort.

Here, Tokarczuk departs from a popular trend in recent historical fiction, which is the retelling of familiar stories with a feminist revisionist slant. In novels such as Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls (2018) and Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet (2020), the focus is on moving marginalised voices to the centre of the story, and on the restoration of female agency and dignity. The novels are as reflective of current political discourse as they are of historical research. Emma Herdman, editor of Madeline Miller’s Circe (2018), argues that the appeal of these novels is their appeal to current concerns: that ‘the comfort of a story that’s already known’ has the effect of ‘mak[ing] contemporary debates more accessible’.

In The Empusium, by contrast, the marginalised voices remain hidden in darkness, and the past Tokarczuk depicts is discomfiting and utterly strange. Though her approach to narrative voice and characterisation is different, what Tokarczuk shares with her contemporaries is an outrage at current injustices; she admits that the novel germinated out of ‘anger and spite’. It is impossible to read The Empusium without the current Polish context in mind. The Vice-Chair of a recent UN report stated that, due to the country’s restrictive abortion laws, the situation in Poland ‘constitutes gender-based violence and may rise to the level of torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment’.

The Empusium is also a mystery. It draws on the conventions of gothic literature and weird fiction. In between appointments with doctors and sessions of hydrotherapy, the men of the guesthouse imbibe Schwärmerei, a liqueur that is brewed from hallucinogenic hooded mushrooms. Wojnicz grows increasingly paranoid: there are deaths at the resort that cannot be accounted for by tuberculosis alone, the men seemingly growing sicker rather than improving. Then there are the charcoal burners, the near-wild men that live in the Stone Mountains and worship the tuntschi, the primordial female spirits of the forest.

As the horrors mount, Tokarczuk creates an atmosphere of dread and suspense, a turning of the screw. The translation, by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, does not have the agile, nimble quality that Jennifer Croft, the other principal interpreter of Tokarczuk’s work, brought to her magisterial translations of Flights (2017) and The Books of Jacob (2021). But Lloyd-Jones’s prose is sensuous and lush, the Görbersdorf sanatorium and its surroundings conveyed with unsettling imagery. Describing the soot-faced charcoal burners’ settlement in the woods, Lloyd Jones suggests that ‘the skin of the forest had been ripped off, leaving the wound inflamed’.

Moreover, our nervous protagonist Wojnicz is a synaesthetic, highly sensitised to an environment that hums with mystery. As the men of the guesthouse pose for a photograph in the forest, it seems as if ‘they are standing on a stage’, and the ‘spectators are the trees, the blueberry bushes, the moss-covered stones and some fluid, ill-defined presence that is moving like streams of warmer air among the mighty trunks, boughs and branches’.

The novel builds to a hallucinatory and bloody climax. In the final few pages, the dark spell that Tokarczuk has so expertly cast is almost undone by an astounding, regressive twist. It is an unfortunate authorial decision and one that creates confusion for the sake of shock.

With her ‘story of patriarchal horror’, Tokarczuk embraces a genre that gives form to her outrage and disgust. The misogynistic ideas that shape the sensibilities of her characters remain widespread in today’s world. The Empusium is a cry in the dark, a primal scream; an unleashing of anger against male writers long dead.

Comments powered by CComment