- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Does leadership matter?

- Article Subtitle: A portrait of eight key leaders

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his 2015 study of Joseph Stalin, historian Stephen Kotkin suggested that the Bolshevik revolution could have been stopped by just two bullets: one aimed at Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, hiding across the border in Finland but pressing the Bolshevik Party to seize power; a second bullet for Leon Trotsky, on the ground in Petrograd as a determined band of Red Guards, sailors, and soldiers stormed the Winter Palace.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Glyn Davis reviews ‘The Titans of the Twentieth Century: How they made history and the history they made’ by Michael Mandelbaum

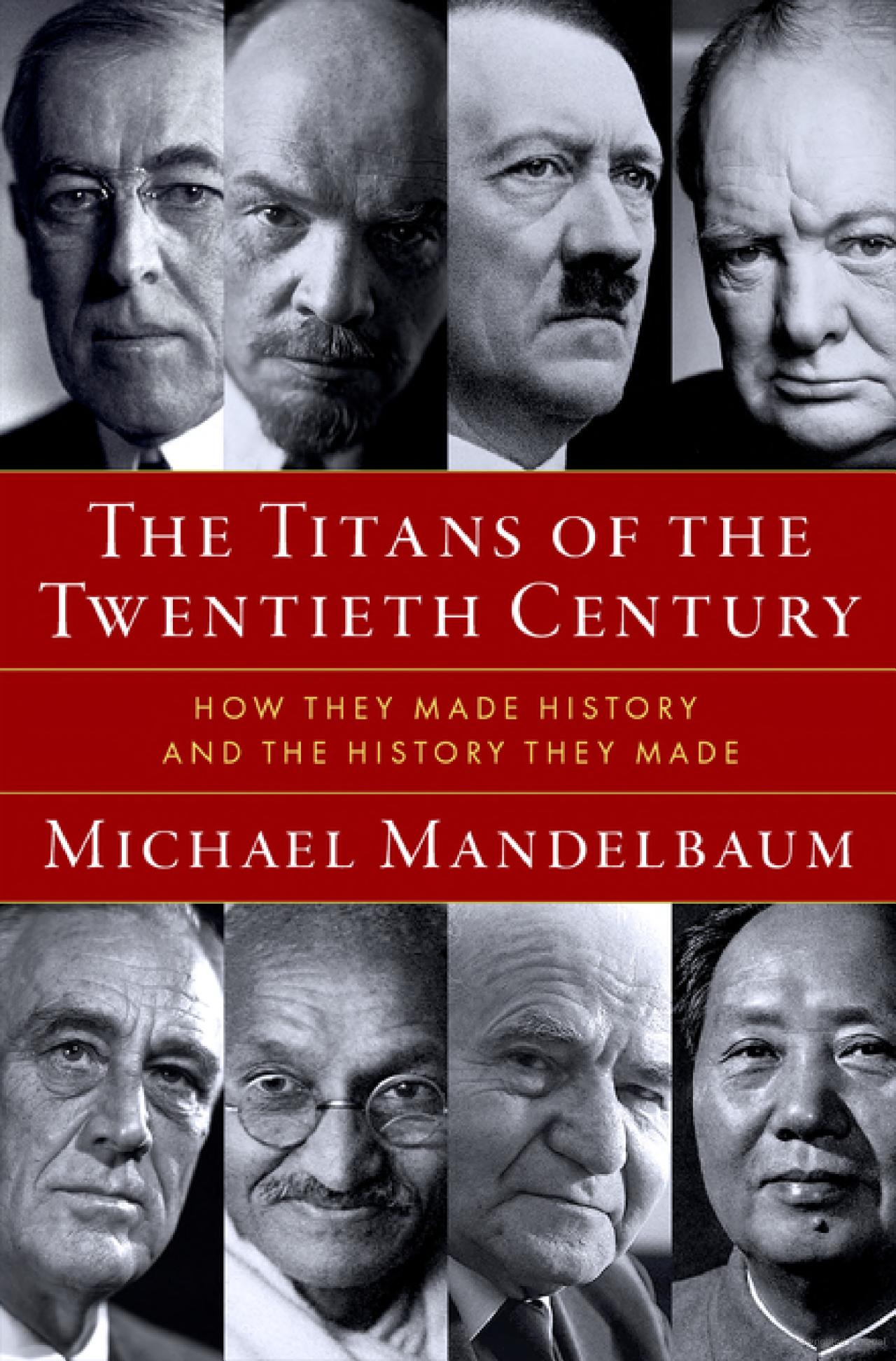

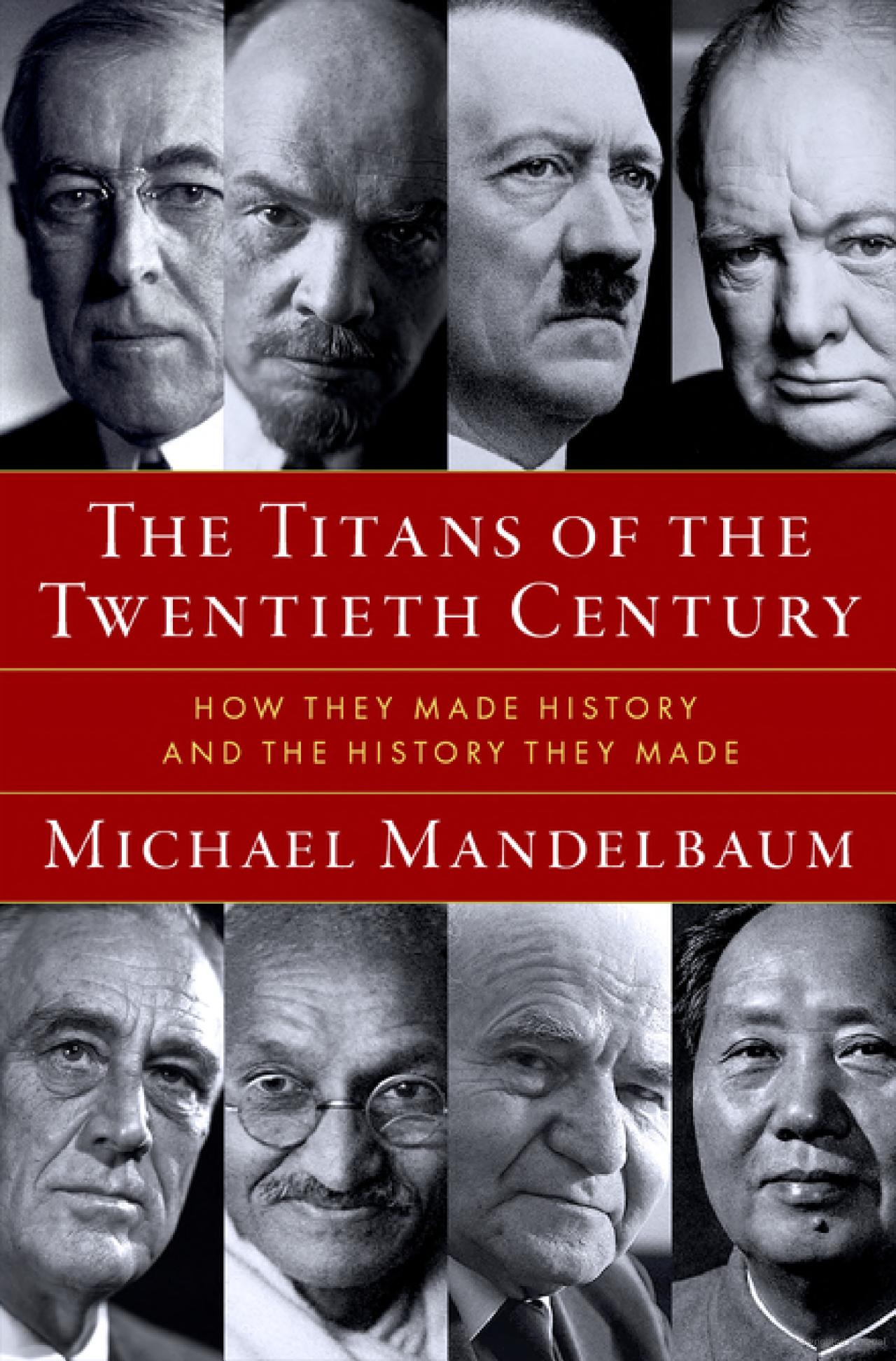

- Book 1 Title: The Titans of the Twentieth Century

- Book 1 Subtitle: How they made history and the history they made

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, £26.99 hb, 347 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780197782477/titans-of-the-twentieth-century--michael-mandelbaum--2024--9780197782477#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

How does a historian tell this story? A biographer might stress the single-minded determination and extraordinary self-belief of Lenin. A historian of Russia might note the failure of the Romanov regime to accommodate demands for a more representative government, even after the vivid warning of the 1905 uprising. This left the nation without established institutions or experienced politicians when Tsar Nicholas II fell. A student of global politics might emphasise the consequences of military defeat, which ended several empires and left many states vulnerable to assault from the margins.

In The Titans of the Twentieth Century, Michael Mandelbaum, Professor of American Foreign Policy at the Johns Hopkins University, offers five levels of analysis for eight key figures from the twentieth century. Each chapter starts with the life, outlines the times, explores the style of leadership, reviews the personal impact of the individual, and closes on their impact after death. So we start with Lenin’s childhood in Simbirsk on the Volga River, then learn about revolutionary movements in tsarist Russia (Lenin’s older brother, Aleksandr Ilyich Ulyanov, was executed for his involvement in a plot to assassinate Alexander III). As a leader, Lenin studied Marx but did not accept the historical inevitability that Marx assigned to the industrial proletariat. Instead, Lenin argued that a disciplined vanguard party could quicken the pace of change and target even largely agricultural Russia for revolution.

Turning to the times, Mandelbaum tells the story of World War I from a Russian perspective, the swift collapse of the Romanov dynasty in 1917, the struggle to establish the Provisional Government, and the resulting vacuum so skilfully exploited by Lenin. Mandelbaum acknowledges Lenin’s charisma – ‘an almost hypnotic effect on those within his personal orbit’ – while stressing an unattractive personality and a propensity to violence. Once in control, Lenin exercised personal power with a ruthlessness rarely seen in human history, an attribute Mandelbaum also assigns to Mao Zedong, complete with the resulting headcount in deaths. The portrait closes with an assessment of legacy – the state Lenin created, the pattern of governing he established, the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union nearly seventy-five years later.

This is the basic pattern of the book, repeated in eight portraits of ‘titans’, those individuals who, according to Mandelbaum, shaped the twentieth century’s most significant moments. The schema introduces a degree of repetition since most of the titans lived through the same events. The United States predominates, with Mandelbaum choosing Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt among his key figures of the century. From Europe, Lenin is followed by Adolf Hitler and Winston Churchill. India is included through Mahatma Gandhi, China through Mao. Israel is represented by David Ben-Gurion. No Africans or Arabs, no one from Southeast Asia, the Pacific, or South America, and, pointedly, no women. Mandelbaum presents this as a reflection of the times; his choice of titans are all men ‘because no woman had a comparable leadership role in the first half of the twentieth century, the period that this book covers’.

Such choices invite a quarrel. They arise from the design of the project and its starting conceit that individuals make history. Not that Mandelbaum misses the context. To shape global outcomes, nations require an industrial revolution, a role in the world economy, and an organised state. On his account, the titan also needs conflict, so that his subjects can initiate or respond to global events. The titans bring to their roles a world view which guides their actions, and personal attributes which shape their choices – the inability of Wilson to compromise, the arrogance of Hitler in overriding his generals on crucial matters of strategy. Structural differences also matter in this narrative: democratic leaders must persuade, while Mao can impose a catastrophic policy even on his own unwilling party. Mandelbaum describes the Cultural Revolution unleashed by the Chairman in 1966 as ‘one of the most bizarre episodes not just in the long history of China but in the history of any country’.

Events provide openings. The Depression gave Hitler the chance to move from the fringes of German politics, just as it enabled FDR to break decades of Republican wins in presidential elections. Ben-Gurion first benefited from, and was then set back by, great power geopolitical calculations. Gandhi invented new forms of protest, some drawn from Indian tradition and others from the Suffragettes he encountered in London, but his aspiration for Indian independence ultimately depended on a change of government in Westminster. Separating the person from the moment, the context from the opportunity, the inevitable from the chance outcome, can be a matter of viewpoint.

Michael Mandelbaum is a skilled analyst who presents his eight portraits with verve. Many of his findings are compelling – no Hitler, no Holocaust. It is possible to disagree with other conclusions yet still enjoy the argument and learn much about a world already fading as new realities, new configurations of power, and new leaders come into focus. Mandelbaum has set himself an impossible question: do individuals make history at global scale, or do time and chance determine the outcome? Like many great investigations, the exploration is more interesting than any answer.

There are circumstances, of course, when leadership does matter. Take the sustainment of a distinguished Australian literary journal. It requires an extraordinary breadth of interests and contacts, a skilled editor and chief executive, soother of egos, dedicated fundraiser, and manager of a complex production process – all in the shape of a single person. Here we can say with confidence that the individual matters. Since 2001, Peter Rose has made the ABR indispensable. Such a remarkable record may not earn the same treatment as a book on global leaders, but the skill and commitment required have much in common. From the community of readers and writers you have made part of this project, thank you, Peter.

Comments powered by CComment