- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sinking into the folds

- Article Subtitle: Annie Ernaux rewrites grand narratives

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A chronicler of experience and a scrutineer of memory, Annie Ernaux always tries to express something universal. By recording her experiences – of the working class, social mobility, abortion, death, divorce, jealousy, affairs, desire, and more – she asks her readers to see their lives in her writing.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Beth Kearney reviews ‘The Use of Photography’ by Annie Ernaux and Marc Marie

- Book 1 Title: The Use of Photography

- Book 1 Biblio: Seven Stories, Press $45 pb, 144 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781804271148/the-use-of-photography--annie-ernaux--2024--9781804271148#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Ernaux’s latest release in English, The Use of Photography, co-authored in 2005 with her romantic partner at the time, Marc Marie, and translated by Alison L. Strayer, extends this project. While Ernaux again preserves and records personal, though relatable, experiences, the ‘use’ of photography here is far more plural and incongruous than in her other works. Ernaux and Marie work with the big ideas surrounding photography while complicating and rewriting them.

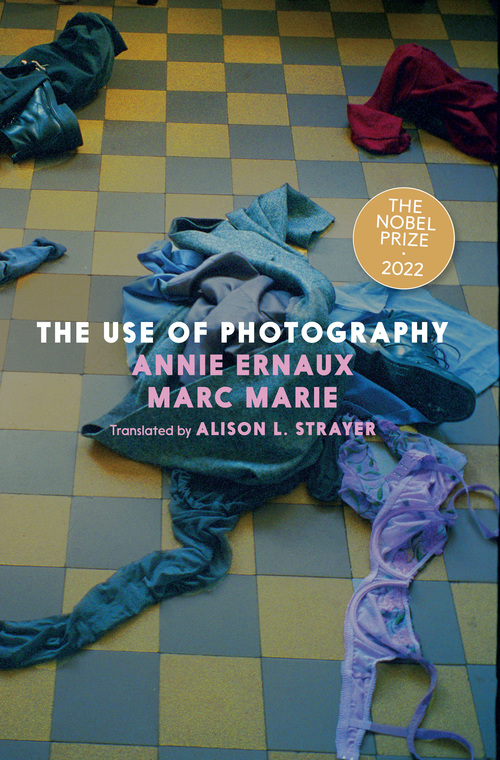

The Use of Photography has two narrators: a woman, ‘A.’, who is undergoing treatment for breast cancer, and her lover, a man named ‘M.’. All chapters – bar the first and last, which are authored by Ernaux – open with a snapshot of the couple’s clothing crumpled on the floor, discarded in the haste preceding sex. In each chapter, the narrators – A. first, then M. – reflect on the scene and the experiences attached to it. The reader, thrust into the universe of the romantic duo, observes the relationship from two perspectives and grapples with notions as impalpable as death and life, illness and sexuality, vulnerability and vitality, reality and unreality. Ernaux and Marie thus tackle aspects of experience common to us all, while expressing a desire to halt the present moment as it slips away like quicksand.

For some, photographs are melancholy: snapping a scene is like pulling a trigger, because the moment captured will never exist again. Ernaux and Marie inherit this attitude by contemplating A.’s troubling condition and the possibility that she is hurtling toward the grave. When visiting the tombstone of M.’s mother, for instance, A. hallucinates: ‘I imagined my name on the stone instead. I saw it very clearly, but it wasn’t real.’ The photographs, emptied of people, echo the morbid themes of the text by depicting, or predicting, her future absence: ‘Here there is no more life or time. Here I am dead.’

Ernaux and Marie’s phototext reworks this well-trodden narrative, for these images are just as much about the intensity of life as about its end. Though the passages of text describe A.’s body – hairless and punctured by a catheter, worn for eighteen months – as vulnerable, the photographs testify to another truth: she is full of desire and sexual vitality. A tangled G-string, a lacy bra on the kitchen floor – these scenes don’t fit the script for a sexagenarian battling a life-threatening disease. Contra the grand narratives of feminine sexuality, the images suggest that an ageing and unwell woman can be an erotic subject. This is classic Ernaux: as ever, she deconstructs gender norms and in turn liberates her readers; she tells the kind of story – one by a breast cancer patient – that she believes should be told more often.

The shameless exposure of sexuality echoes the feminist themes so common in Ernaux’s œuvre (think Simple Passion [2021], recently adapted to the cinema). The visceral close-ups of underwear and voyeuristic peeks into the authors’ homes reveal things and spaces that are supposed to remain hidden. Yet while they expose, they also conceal by hinting at the nude figures beyond the frame.

Ernaux and Marie, who do not include images of the sexualised bodies described in the text, refuse an objectifying gaze on the female body. In fact, A. uses writing to objectify M.’s body: ‘I feel a peculiar excitement in handling and adjusting the zoom, as if I had a male member.’ While M.’s erotic descriptions are at times timorous – he writes of ‘the look on her face when she came’, for instance – A. is far more explicit: his ‘sex, seen in profile, is erect. The light from the flash illuminates the veins and makes a drop of sperm glisten at the tip.’ This photograph (not printed in the book) cuts M.’s face from the frame. And when A. writes that a bookcase ‘occupies the entire right part of the photo’, she calls attention to her intimidating status as an internationally renowned author. These detailed descriptions recall the realism (mistakenly) understood to be an inherent feature of photography. But Ernaux and Marie complicate this narrative about the medium, too. While they write that their images are ‘tangible evidence of what [they] had just experienced’, they also consider them to be totally unfixed from reality, ‘as if M. has photographed an abstract canvas’.

Citizens of today’s post-truth era are already suspicious of photography’s claims to veracity, but Ernaux and Marie’s message is more nuanced. Truth, they suggest, can be subjective, plural: ‘The highest degree of reality … will only be attained if these written photos are transformed into other scenes in the reader’s memory or imagination.’ The Use of Photography is among only three of Ernaux’s works with printed images (rather than solely ekphrastic descriptions). It thus sits apart from her other literary experiments with photography: though she again transcribes universal experience, she does so by asking readers to create their own meaning from the words and photographs, to imagine themselves colonising the empty interiors, sinking into the folds of the uninhabited garments.

Comments powered by CComment