- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Photography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Just holding the fort’

- Article Subtitle: Two books on documentary photography

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

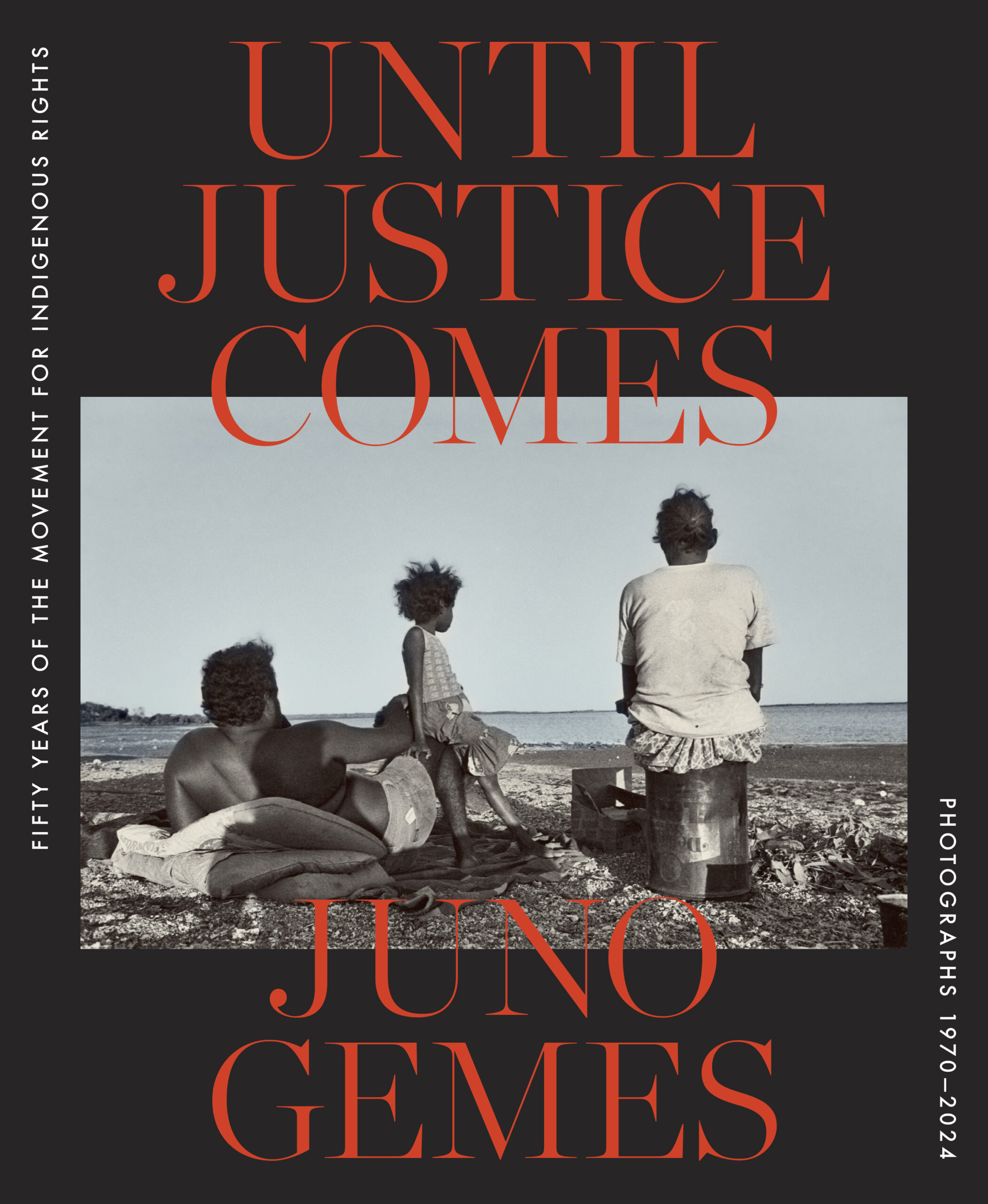

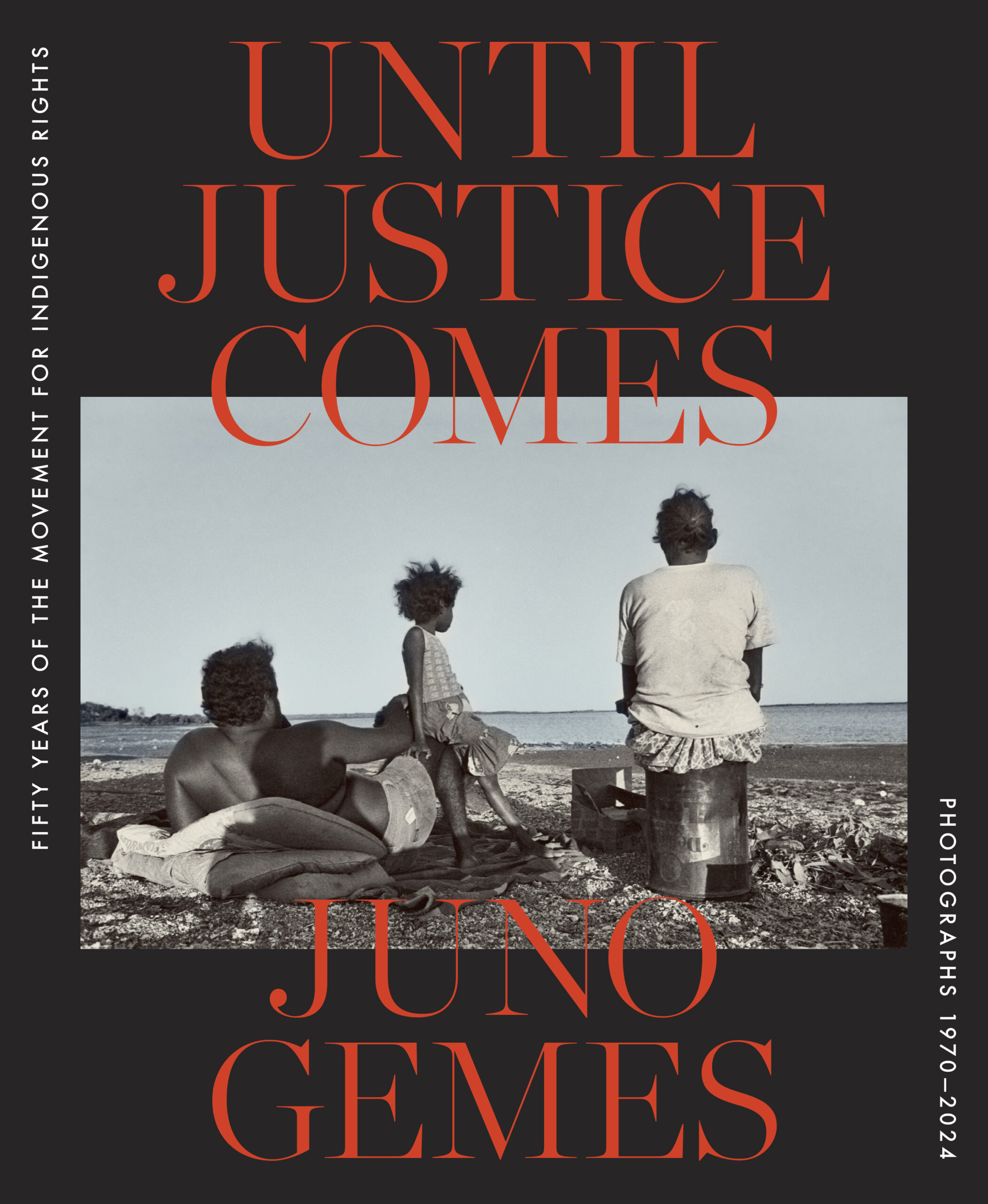

Photography finds itself at yet another crossroads. In an era of artificial intelligence, the photograph’s role as a document of evidence has again come under the spotlight. Entering this disruptive space are two new documentary photography books: Juno Gemes’s Until Justice Comes: Fifty years of the movement for Indigenous rights. Photographs 1970-2024 and Stephen Zagala’s Imagining a Real Australia: The documentary style 1950-1980. The focus of these books is vastly different. Gemes offers a contemporary history of Australia, whereas Zagala is more concerned with the documentary genre. Their existence affirms that, while the truthfulness of photography may be contested, as it has been since the medium’s nascent years, the intrinsic value of documentary photography remains undiminished. In fact, at this juncture, documentary photography may prove even more important as we grapple with notions of what is ‘real’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Alison Stieven-Taylor reviews ‘Until Justice Comes: Fifty years of the movement for Indigenous rights. Photographs 1970-2024’ by Juno Gemes and ‘Imagining a Real Australia: The documentary style 1950-1980’ by Stephen Zagala

- Book 1 Title: Until Justice Comes

- Book 1 Subtitle: Fifty years of the movement for Indigenous rights. Photographs 1970-2024’

- Book 1 Biblio: Upswell, $65 pb, 325 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780645984026/until-justice-comes--juno-gemes--2024--9780645984026#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

- Book 2 Title: Imagining a Real Australia

- Book 2 Subtitle: The documentary style 1950-1980

- Book 2 Biblio: NewSouth, $59.99 pb, 197 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781742236926/imagining-a-real-australia--stephen-zagala--2024--9781742236926#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

In the 1970s, Hungarian-born, Sydney-based photographer Juno Gemes travelled to an Aboriginal camp outside of Alice Springs. As she sat with elders, women, and children, Gemes’s innate curiosity stirred, sparking a deep desire to understand more about the world’s oldest culture. Thus began a collaborative relationship of ‘sharing and learning’ that unfolds across five decades in her Until Justice Comes.

The title comes from a remark made in 1972 by Mum Shirl, an icon of The Movement for justice: ‘I am just holding the fort until justice comes.’ Gemes describes the book as ‘a contemporary history of Indigenous activism’. While I agree, Gemes’s photographs are framed by a larger social and political narrative, which positions the book as a vital contemporary history of Australia. It is also a heartfelt tribute to and celebration of an extraordinary people and their continued optimism in the face of adversity. Resilience, strength, and a fierce sense of identity run through the decades, showing why the fires of hope keep burning. But there are also stories of profound loss and grief.

As a photographer, friend, and campaigner in The Movement since the 1970s, Gemes has been on the frontline, documenting the most significant historical happenings. These include the 1982 Brisbane land rights protests, the 1985 Uluru handback ceremony, the 2008 Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples (Gemes was one of ten photographers invited to Parliament House), the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Uluru handback (2010), the fiftieth anniversary of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra (2022), and the meeting of the Referendum Advisory Committee at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (2023). Gemes has also been there for everyday moments, turning up with her camera through the decades to capture weddings, music festivals, theatre events, and family days. The combination of the political and the personal makes for a rich history.

Selecting the 200-plus images for Until Justice Comes took Gemes more than three years, a collaborative effort echoing her photographic practice. Insights into Gemes’s approach and her analytical mind are also found in her collages, proof sheets, and written testimony. These works reveal her compassion, erudition, and passion for telling and continuing to draw focus on this enduring story.

Gemes’s wide-ranging narrative counters the narrow framing of mainstream media, where the focus is mainly on poverty, crime, and despair. Until Justice Comes conveys joy and strength, grief and rage. One of the book’s standout features is women’s contribution to The Movement. You cannot reach the end of this extraordinary tome without being touched by the profound humanness of this history, Australia’s history, and the fight to see justice served.

I am drawn to many photographs in this collection, but two are notable. These pictures reflect the power of a masterful storyteller. First is a picture taken at the Uluru handback twenty-fifth anniversary (2010). Uluru dominates the background, reaching to the sky as the green/grey scrub and the vibrant ochre earth roll towards the camera. At the front of the frame are two Anangu women dancing the inma, a performance that connects people to the Law and Dreaming of their country. Their traditional body paint and feather headbands contrast with flowing black skirts. They move with their hands open in a gesture of giving and acceptance that exudes generosity and love.

Second is the portrait of Linda Burney, Minister for Indigenous Australians, at a pre-dawn media conference at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park in 2023. This picture opens the final chapter in the book: ‘After the Referendum’. Burney is illuminated by an artificial spotlight. In the background, Uluru’s immensity, cloaked in shadow, rises to greet the day. The sun casts a deep, burnished glow on the horizon. This image presents strength, vulnerability, courage, and resolve. An icon of The Movement, Burney is a minor figure in a sweeping vista, yet an integral part of the landscape.

Until Justice Comes provides an unprecedented documentation of our First Nations People and is an essential contribution to Australia’s history. Gemes’s photographs are paired with essays by luminaries in The Movement, politics, and academia; and poetry by Robert Adamson, Gemes’s late husband, and Ali Cobby Eckermann, a Yankunytjatjara woman and Stolen Generations survivor. As Burney observes in the Foreword, ‘After the crushing defeat of the referendum, this country is finally waking up to the importance and power of truth-telling. The truth is in these pages.’

Imagining a Real Australia: The documentary style 1950-1980 celebrates, and critiques, work made over a period that author and curator Stephen Zagala describes as the ‘golden age of documentary photography’, a genre whose origins began in the middle of the nineteenth century. The book is presented in five chapters. The first, ‘Real Style’, canvasses how the genre developed, revealing the stylistic trends and political and societal influences that shaped an ‘Australian’ way of seeing, one that was focused on nation building. It considers the emergence of humanistic photography, photojournalism and street photography, and draws on the work of Max Dupain, Mark Strizic, Lawrence LeGuay, and Maggie Diaz, among others.

‘Real People’ captures the rise of the feminist voice and the power of photography as activism. It reveals the emergence of ‘the personal turn’ explored in the work of Ponch Hawkes, Carol Jerrems, Sue Ford, and Ruth Maddison. The exploration of ‘self’ becomes a cultural metaphor for the experience of women, a way of looking and seeing ourselves beyond the social norms and expectations of the day.

Perhaps the most eclectic section, ‘Real Space’ explores the social spaces that draw photographers. Pictures capture the migrant experience, Aboriginal activism (Gemes’s work features here) and technological advances. There is also personal work by the likes of Max Pam, John Gollings, and Paul Cox.

‘Real Movement’ examines how photographs circulate, a premise established through a brief historical discussion on publications, exhibitions, and printed artefacts, institutional and personal. This chapter also refers to the shifting boundaries of documentary photography and innovations in storytelling. Consider Ruth Maddison’s hand-coloured ‘Christmas Holidays with Bob’s Family’ (1977-78) and Helen Grace’s observational ‘Christmas Dinner’ (1979) as examples of how family is portrayed. William Yang’s exquisitely intimate ‘Joe’ (1979), where the photographer has noted his observations across the image, rounds off a chapter that spans portraiture to photojournalism.

‘Real Futures’ centres on the ‘critical repurposing of the documentary lens by First Nations photographers’, and features work by Ricky Maynard, Polly Sumner-Dodd, and Brenda Croft. This section shows a range of documentary approaches underpinned by intimacy, collaboration, and relationship building. As Croft, a Gurindji/Malngin/Mudburra woman, says, ‘By placing myself behind the camera, I am taking control of my self (sic) and images of ourselves.’

Imagining a Real Australia is a welcome addition, given the limited attention so far paid to the documentary form in this country.

Comments powered by CComment