- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: ‘Congratulations Bob’: The Petrov Affair and the Australian public

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: ‘Congratulations Bob’

- Article Subtitle: The Petrov Affair and the Australian public

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On a Tuesday morning in April 1954, Australians awoke to sensational headlines. The wife of Soviet diplomat Vladimir Petrov, who had recently sought asylum in Australia, was dragged aboard an aircraft in Sydney, as an impassioned, noisy crowd of a thousand tried to prevent her departure. Whether you were a dock worker or a stockbroker, your morning newspaper carried some version of what has become the Petrov Affair’s most iconic image: Evdokia Petrova, shoeless and eyes streaming, flanked by two bulky Soviet couriers, marching her across the tarmac. By all appearances, a terrified Russian woman was dragged, unwillingly, towards a dire fate in the Soviet Union.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): ‘“Congratulations Bob”: The Petrov Affair and the Australian public’ by Ebony Nilsson

The lost shoe is often remembered as red – the colour of communism, or high emotion. In fact, it was blue. Petrova never did yell in Russian that she wanted to stay (as many onlookers would later swear she had); her tears were an allergic reaction to the brandy taken to calm her nerves, and her fear was of the crowd rather than her Soviet minders. But with this black-and-white photograph, the narrative wrote itself. The Cold War, something which happened in far-off cities like Berlin, Washington, or Moscow, had come to Australia. But this wasn’t about political ideology, about nationalising the banks or protecting private property. It was the figure of a lone, pretty, blonde woman struggling against two hulking communist brutes. This was a story of good, evil, and espionage.

The political affair had begun with Vladimir’s defection a fortnight earlier, but it went on to span the rest of 1954 and a good portion of 1955, with the subsequent Royal Commission. The Commission’s revelations about Soviet espionage captivated the public’s imagination and changed Australia’s political landscape. This latter story is well known: H.V. Evatt met his political demise, and the Labor Party fractured. But what did the Affair, with its lengthy public inquiry and sustained media attention, mean for Australians who didn’t generally concern themselves with the Labor Party’s backroom drama?

This is an irresistible question for historians who, like me, want to understand what ‘ordinary’ people thought, felt, and did. Politics meant something different for a metal worker in Geelong or a housewife in Marrickville, say, compared to the activist, lawyer, or politician. Their views often fitted less neatly within boxes such as ‘conservative’ or ‘left’, and need not even be logical. The difficulty lies in finding these views, when their owners weren’t usually the type to write down their political musings. Opinion polling provides some clues. Gallup polls in 1954 showed cost of living looming larger for Australians than espionage. But polling data has its limitations. It shows only answers to the questions posed – not the many and varied, sometimes wild and wacky, opinions which people held.

So what did Prime Minister Robert Menzies’ ‘forgotten people’ (whoever they are) make of the Petrov Affair? Some of them wrote about it to him. Letter writers never represent a perfect cross-section of society. We only hear from those who cared enough to take the time. But the letters Menzies received regarding the Petrov Affair and Royal Commission do broaden our gaze, giving us a window into the varied and sometimes unexpected issues which Australians cared about. Searching through boxes of these letters, I was struck by how personal they often were. These letter writers, and presumably others, felt connected to the Petrov story; they felt everything from sympathy for the two Russians to deep suspicion about their motives. Many felt that they themselves might play a role in the drama, whether by assisting the Commission or simply offering Menzies humble (or not so humble) advice.

Migrants from the Soviet Union had a particularly personal connection to this story. Many were recent arrivals displaced by World War II and fleeing communism, so the story of Soviet citizens ‘choosing freedom’ in the West hit home. They wrote to Menzies from Footscray to Fitzroy, Daylesford to Adelaide, and even further afield: Auckland, Paris, San Francisco, and more. Most expressed gratitude and appreciation, placing the prime minister on the right side of history. H. Beukers of Northwood, Sydney, wrote on behalf of all migrants: ‘We as migrants feel you did the right thing and our opinion is only “get rid of those communist [sic]”. Communisme (sic) is already no good in itself and specially ruins Australia.’ These letters also convey pride in the actions of their new, adopted home.

Australian-born writers also felt proud of Menzies in light of Evdokia’s ‘rescue’. From Adelaide (‘grateful and proud to have you as our leader’) to Brisbane (‘Australia has been right on top of the game throughout the whole play’) to the Sunshine Coast (‘with thankfulness and pride I … express the feelings of many Australians’) they sent best wishes. Bert Watson of Sydney was delightfully casual, writing: ‘Congratulations Bob you have definitely won the hearts of the people over your splendid handling of the Petrov Case.’ S.S. Robinson, a returned soldier, proclaimed simply, ‘thank God I’m British’. For some, this good feeling extended beyond Menzies: James Hegarty, from a tiny village in the Hunter Valley, asked that his appreciation and best wishes be conveyed also to ASIO and the Petrovs themselves.

Many Australians apparently felt connected to the Petrovs, particularly Evdokia. Roy Robe of Orange told Menzies that he and his daughters had been so worried they had ‘united in earnest prayer’ for Evdokia, a gesture that he thought might comfort and inspire her. Several extended spiritual wishes to these presumably godless communists, hoping that, with a new life under capitalism, conversion might follow. Josephine Mitchell, from country Victoria, even enclosed a book on Jesus that she felt sure Evdokia would enjoy, and which, it appears, was indeed delivered to Petrova, care of ASIO. While sympathetic, these missives also conveyed an undercurrent of excitement, the ‘thrill’ the writers felt. These were dramatic events, after all. R. Francis of New Zealand wrote that, despite his advanced age (over forty-five!), he wished he could have been present at the airport ‘to put those two hooligans in their proper place – on the floor. Types of that sort only assimilate lessons through their hides.’

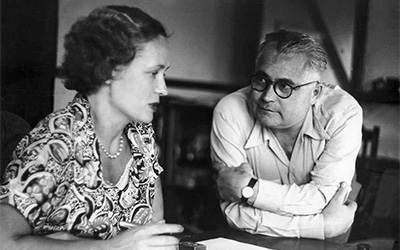

Evdokia and Vladimir Petrov, Sydney (courtesy of National Museum Australia)

Evdokia and Vladimir Petrov, Sydney (courtesy of National Museum Australia)

As the Royal Commission on Espionage began in May 1954, however, the tenor of the public’s letters shifted. The Commission hearings, held in Canberra, Melbourne, and Sydney, went for five months and were almost entirely open to the public. Residents of all three cities turned out in droves to watch this real-life spy drama unfold. Both Petrovs testified publicly, as did several ASIO men. The Commission brought Australia’s intelligence service, established only six years earlier, out of the shadows. At the Royal Commission, one could go and see real spies tell stories about their work. Australians learnt about Russian spies frequenting Sydney bars and nightclubs, clandestine meetings in cemeteries and parking lots, and their own security service running agents on the same streets they themselves walked.

The more information the public received, the more they felt they had to tell Menzies. Letters providing advice to the prime minister began to flood in during the commission hearings. On foreign policy and security, ordinary Australians had thoughts. Cutting diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union risked war but also the economy, they told him. One Sydney-sider was inspired to put his thoughts into rhyming verse while another, A.F. Marshall, warned Menzies that China posed the real threat. It was poised to take control of the Soviet Union and already, he thought, operated an Australian spy ring. Mr Kiernan of Ascot Vale had ideas for ASIO: microfilm all mail sent and received by communists and fellow travellers, before sending it on. Kiernan either overestimated ASIO’s capacity or underestimated the sheer amount of mail involved, but, either way, ASIO was not, it appears, apprised of his thoughts.

Others thought that the Petrovs – Vladimir, particularly – were shifty characters about whom Menzies should be warned. Mrs Melrose of Brisbane was succinct: ‘I do respectfully suggest Do not put faith in traitors.’ R. Thomas of Hawthorn wrote earnestly, concerned that Petrov would be Menzies’ downfall, exclaiming: ‘None of my friends think Petrov is telling the truth. He’s no good!’ Others suspected nefarious Soviet tactics afoot. Fred White of Perth wrote to advise that Petrova might well be ‘under hypnotic influence’, while one C. McCafferty of Sydney suggested it was likely drugs.

The other topic that invited criticism was money: the cost of the Commission expanded as its hearings drew out. In a time-honoured tradition, many – particularly trade unions – wrote of the government’s ‘waste of tax-payer funds’. But the causes to which correspondents thought Menzies should divert the money were revealing. A Newcastle railway shop committee suggested it would be better used for ‘prevention of flooding in the Hunter Valley’. Other unions suggested, perhaps optimistically, that the clear path was to invest the cash into improving workers’ conditions.

Women seemed especially galvanised by the subject of money. Sheila Irvine, a war widow from Richmond, described her life on the breadline. ‘The contrast is blatant,’ she told the PM. ‘We want homes and decent living conditions, not war and Petrovs, deport them from the country and allot the money … to housing the war-widow.’ Women, it seems, often thought social policy more pressing than espionage or communism. Zara Mathew of North Carlton called on Menzies to divert commission funds to ‘homes, hospitals and schools’. Doris McRae of Armadale conveyed her alarm at The Age’s report: the Commission would cost at least £65,000 in 1954 alone. Could some, she asked, not be put toward old-age pensions?

Australians felt involved enough in the Royal Commission to offer Menzies advice, often personally – man-to-man (or, less often, woman-to-man). Many went one step further, offering their help. I was surprised, leafing through these files, at how many people thought they might hold the key to this spy inquiry. Some were cryptic, offering a name and a phone number. ‘He is clever. I thought you might be interested,’ wrote D. Fraser of Galston.

Others felt their experiences provided essential information. Miss Saunders, of St Kilda, had worked at Australia-Soviet House for John Rodgers, a person of interest at the Commission. The key to nailing him, she told Menzies, was to track down his former secretaries: they knew all. Alan Reginald Burch, a former Navy man from Noosa, wrote with a tale of a train trip he took in 1927 or 1928, when he learnt from a group of shearers that one could travel undetected by paying off a ship’s chief steward. This, he was sure, was how a missing commission witness had left the country. Some had begun to see spies everywhere. One Victorian man wrote about receiving an anonymous reply to his newspaper opinion letter (on an unrelated topic). This, he felt, ‘reeks with suspicion’ and ‘may add another link in the chain’ of the Petrov inquiry. A woman claiming to be one Miriam Dalrymple, Viscountess Stranraer, offered her services in ‘counter-espionage work’ with the Indigenous peoples of Port Hedland. Menzies’ secretary could find no trace of this viscountess and appeared to write her off as fanciful, but Dalrymple continued to offer her (apparently considerable) skills.

Menzies also received a host of letters from individuals who believed they would make good ASIO officers. There was a standard reply: their offer was gratefully received and passed on. How many actually made it into ASIO’s hands is anyone’s guess. Russian language skills were also commonly offered. Some of these were from new migrants, eager to assist in translating Petrov’s documents and to find more fulfilling work than the manual labour mandated by their Commonwealth-assisted passage. These offers were passed to ASIO but not generally accepted, the security service preferring its own, vetted translators.

Finally, a handful of correspondents wanted to assist the Petrovs. Charles Meeking, a writer and Menzies’ own former press secretary, proffered himself as Petrov’s ghost writer, to help Vladimir tell his story to the world. A.B. Turner of Mudgee wrote that the Petrovs were welcome to a half share of his property and livestock, for the tidy sum of £18,000, after hearing that Petrov desired to be a farmer. Two letter writers took it upon themselves to offer assistance not to Petrov, but to his dog – a German shepherd named Jack. After The Sun published pictures of the dog, abandoned by departing Soviet officials, E. Holland of Hunters Hill wrote to Menzies: ‘I feel sure that picture will have tugged at your heart strings as it did at mine.’ Colin Malcolm Wall, whose letterhead proclaimed him a Sydney ‘Inventor of Products’, offered to look after Jack himself, even at the expense of driving to Canberra to collect him. In a postscript, he assuaged any of Petrov’s anxieties about the plan by underscoring his strong anti-communist credentials.

Jack was eventually returned to the Petrovs at their ASIO safe house, while most of the advice and assistance offered to Menzies went unheeded. At best, the author would receive a stock reply from Menzies’ secretary, acknowledging receipt and noting their representations. Many probably never made it onto Menzies’ desk for review. But they provide a glimpse of the kinds of political concerns shared over kitchen tables or pints at the pub.

The Petrov Affair was about the Cold War for many: it brought the communist threat close but also a feeling of Australia’s importance on the global stage. With the Royal Commission, there was a degree of excitement. An individual member of the community might have their own role to play, because of something they had heard, a person they knew, or a pamphlet they had received. But Menzies’ correspondence also shows that the spy scandal was not front of mind for everyone. There were plenty of other, more immediate concerns: pensions, the economy, schools, and hospitals. Nevertheless, this political scandal felt personal to some. Politics are never detached from circumstance or emotion, and we become personally invested, particularly when there is a good story involved. Australians engaged with the Petrov Affair, like many other political scandals, because of the power of its narrative – whether they perceived it to be about good and evil, freedom and peace, Australia’s place in the world, or simply a dog that needed a home.

This is one of a series of ABR articles being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment