- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Wir schaffen das

- Article Subtitle: Memoirs of an enigmatic chancellor

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Just a few years ago, retiring after sixteen years as Germany’s chancellor (2005-21), Angela Merkel was praised to the skies as a stateswoman who represented all that was admirable in a (semi-)united Europe. Now her reputation has taken a nosedive (‘Angela who?’ The Economist asked, tongue in cheek, last October). That’s an occupational hazard for politicians, and Merkel, as a seasoned professional, knew the score. Still, she deserves to be remembered, if only because in 2015 she did something that seasoned professionals very rarely do: ignoring the risks, she took an important political decision for moral reasons. That decision was to open Germany’s doors to thousands of refugees from North Africa and the Middle East – in the end almost a million – desperately trying to enter Europe via the Mediterranean.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sheila Fitzpatrick reviews ‘Freedom: Memoirs 1954-2021’ by Angela Merkel with Beate Baumann

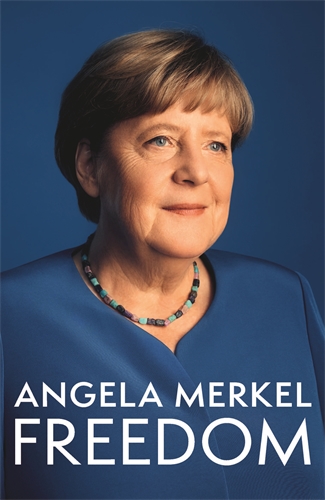

- Book 1 Title: Freedom

- Book 1 Subtitle: Memoirs 1954-2021

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $54.99 pb, 707 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781035020768/untitled-autobiography--anon-anon--2024--9781035020768#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

‘Wir schaffen das’ (we can do it), Merkel said of the refugee problem; and so they could, at least operationally, given the Germans’ famous efficiency and penchant for orderly government. Even on the emotional level it seemed at first that they could do it, with crowds of Good Germans gathering at train stations to welcome the refugees with flowers. It was an object lesson that many admired but no other European state chose to emulate. Then came the predictable backlash: a swing of German public opinion against immigration, terrorist attacks both by and against the newly settled refugees, and the ominous rise of the anti-immigration Alternative for Germany (AfD), the first far-right party since the Nazis to win significant votes at German polls, in the process inflicting severe damage on Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union Party (CDU), which had dominated German politics since the late 1940s.

In hindsight, if you add up the pluses and minuses, Merkel’s grand gesture probably wasn’t worth it. Still, it’s hard not to applaud. In her three decades in the CDU leadership and German government, Merkel’s political style had been characterised by mastery of detail, tirelessness as a negotiator, acceptance that both sides needed to compromise to achieve an outcome, and willingness to let others take the credit if the deal got done. Flamboyance of any kind was alien to her, even in the realm of virtue; ostentatious occupation of the moral high ground was not her métier. But for once she came close to breaking her rule.

Merkel is often referred to as East German, an Ossi. That is true, in that she lived in East Germany for almost all the first thirty-five years of her life. But it is only part of the truth, since her parents were from the West: in 1954, when she was six weeks old, her father, Horst Kasner, moved his family from Hamburg to Brandenburg in the East to work there as a Protestant pastor. This was not a political pilgrimage but something closer to missionary work, given the anti-religious bias of the Soviet-bloc German Democratic Republic (GDR). It came as a tremendous shock to the Kasners when the Berlin Wall went up, trapping them in the East and separating them from their extended families. Seven-year-old Angela learned the value of freedom – enshrined in the title of her memoir – early on through the trauma of losing it, specifically the freedom to move.

At school, Angela and her siblings grew up with the stigma of being children of a pastor. But she was a resilient and competent child who joined the party-sponsored Young Pioneers and at school studied the compulsory Russian well enough to top a national Russian Olympiad in 1969 and win a trip to the Soviet Union. At university, she studied physics, becoming a research scientist at an institute in the Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Her marriage to her university boyfriend, Ulrich Merkel, fell apart, and in the mid-1980s she started living with Joachim Sauer, a scientific colleague in Berlin; together, they bought and renovated a country get-away in the rural region of Uckermark in Brandenburg.

When the Wall came down in 1989, Merkel was exhilarated. She welcomed the unification of Germany that followed, and, unlike many in the GDR, never had second thoughts. Of the new freedoms on offer as a result of unification, one she embraced with particular enthusiasm was the freedom to engage in party politics. Although the rest of her family were socialists, she spurned the SPD in favour of a small, Christian party that soon merged with the CDU. This was not just a matter of joining the party; it seems to have been immediately clear to Merkel that she would change her occupation from scientist to politician. Her rise in the CDU was connected not only to her merits and to the patronage of powerful men, including Chancellor Helmut Kohl, but also to the fact that she ticked boxes as an Ossi and a young woman. In fact, if being an Ossi was the launching pad, being an Ossi with a half-Wessi heart surely helped to propel her upwards in a Western-based Federal Republic of Germany that had not so much unified with the East as absorbed it. Living in sin was a minus for a career in the CDU, and Merkel and Sauer duly married, very quietly, in 1998 – but only some time after Merkel had faced down public criticism from a cardinal without apologising.

Angela Merkel and Vladimir Putin, 2020 (Kremlin via Wikimedia commons)

Angela Merkel and Vladimir Putin, 2020 (Kremlin via Wikimedia commons)

Merkel’s memoir is full of intriguing detail about her relations with other world leaders, virtually all men at the time, among which her friendships with Presidents Barack Obama and Emmanuel Macron stand out. President Trump was, of course, a cross to bear, but as usual she did her best. The other cross, as she tells it in the memoirs, was Vladimir Putin, so full of resentment towards the West and prone to lying that even Russian-speaking Merkel, his natural ally among Western politicians, finally washed her hands of him. That’s probably a harsher portrayal than she would have made earlier: up to 2014, at least, she both understood Putin’s position on Russia’s border security (which led her to oppose Ukraine’s bid for NATO membership in 2008) and supported the construction of a gas pipeline and other measures strengthening Russia’s and Germany’s economic ties. They did, after all, have two common languages (although Merkel says that, despite her teenage Olympiad victory, her Russian was not as good as his German), and grew up in the same political culture. But one can hardly blame Merkel – excoriated, after Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, for having misjudged the Russian threat – for bearing some retrospective grievance against the man responsible.

When Merkel retired from the chancellorship, she left politics with the same absolute single-mindedness with which she had entered three decades earlier. She had always had a life outside politics, although she and her husband kept their private life remarkably private (Joachim Sauer not only skipped his wife’s inauguration as chancellor but also once declined an invitation for dinner à quatre with the Obamas on the grounds of a prior appointment with a colleague in Chicago – a story Merkel doesn’t tell in her memoir). After leaving the chancellorship, Merkel made herself essentially invisible, living with Sauer, as before, in their small Berlin flat and country house in unglamorous Uckermark, presumably continuing to read widely, follow science, go to the opera, and barrack for her favourite soccer team (which gets its own chapter in the memoir). But who really knows? Merkel and Sauer are not about to break the habit of a lifetime and invite the world media into their living room. If the real Merkel has left the world stage, however, a virtual avatar has emerged to fill the gap. The 2024 German television series Miss Merkel (a nod to Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, a long-time German favourite) features a retired Angela and Joachim, who, with time on their hands, have taken to amateur sleuthing, solving a crime a week in the flatlands of Uckermark.

Comments powered by CComment