- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: ‘Shimmering multiple and multitude’: Keeping up with Judith Wright

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: ‘Shimmering multiple and multitude’

- Article Subtitle: Keeping up with Judith Wright

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A year before her death in 2000, Judith Wright’s autobiography Half a Lifetime was published. The phrase ‘female as I was…’ peppered her stories. Miles Franklin’s Sybylla Melvyn had been a childhood idol. Wright conceded that Sybylla’s use of a stockwhip to assert power might have seemed ‘a little over the odds’. Then: ‘but if you had to?’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): ‘“Shimmering multiple and multitude”: Keeping up with Judith Wright’ by Georgina Arnott

Half a Lifetime was the comparably unlikely story of a pastoral girl who became one of Australia’s best known poets and public figures. When, in 1974, Gough Whitlam required a new governor-general, Wright made the shortlist (how different history might have been ...). At the age of thirty-one, her début collection, The Moving Image, (1946) was published, its title invoking Plato’s ‘time is a moving image of eternity’ and foregrounding her philosophical interests, pursued across verse depicting unmistakably Australian landscapes and lives.

Within ten years, Wright was editing major national poetry anthologies and books about Australian poetry. From the 1960s her life shifted direction. Drawn into different ‘causes’, as she called them, through friendships and her wide reading, she in time took up leading roles in environmental, heritage, and treaty movements, and wrote key works in Australian history and valuable biographical accounts of writers, including Henry Lawson, family members, even her husband Jack McKinney. And yet, in the closing pages of Half a Lifetime, Wright warned of the elisions of life writing. She cautioned against stable conceptions of self, thought, action, legacy – that last notion so fundamental to biography. The ‘I’ was a ‘shimmering multiple and multitude’, she wrote, a procession. Each memory might have been told a different way. No game biographer would ever keep up with all those shimmering Judiths. She was familiar with their shortcuts – perhaps ‘solutions’ is better – the seductions of narrative when faced with life’s chaos. For the memoirist, the narrative drive was riven deeper by the ego: ‘Every kind of avoidance, misinterpretation, deliberate forgetfulness, dodge and evasion, aggrandising viewpoint, use of other people and of time and event to cloud the issues, was waiting below the surface of the mind and the text.’

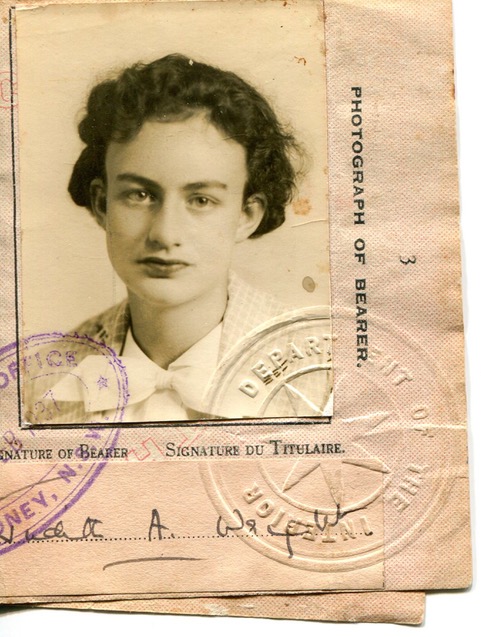

Judith Wright passport, 1937 (courtesy of Meredith McKinney)

Judith Wright passport, 1937 (courtesy of Meredith McKinney)

Wright knew, intimately, how even with access to evidence and fact, stories could be told differently. In Generations of Men, she had walked her reader through the hardships, losses, and aspirations of her forebears, heaving closely to her grandfather’s diaries. In Cry for the Dead (1981), she famously described this same project as an ‘exploitative venture’, an invasion, ‘the great pastoral occupation’ of Indigenous lands. Somehow, though her ancestors peopled this second history and were unexceptional by the terms of their squattocratic class, they were excused in Wright’s narrative, their documented murder of Indigenous people on one tense occasion passed off as an attempted warning.

Further layers of self, more shimmering Judiths, faced the biographer of a public figure. She warned: ‘The most public life is a multiplicity.’ There was a provocation hidden in this ‘Keep Off’ sign, an invitation even: to write her life as a public life, female as she was. In that sentence’s denouement she invoked what seemed a more haunting alternative to documenting lives: ‘The private life of a woman leaves less trace than the silver trail of a slug which dries and blows away.’

It could not be denied. Yet here she was a woman with a public life, and this seemed to justify the 300 pages (there was a kind of Protestant, rural disdain for self-indulgence here). Her final lines of Half a Lifetime: ‘Perhaps somewhere in the thicket she [the memoirist] may meet some useful guide or lay down some trail that can be followed before it dries up and blows away.’

Setting out on my Wright biography, the spectre of a dried slug trail put pace in my step. I put it to Wright’s half-sister Pollyanne Hill that my biography would tell her life as a public intellectual. Not just as a poet or an activist, anthologist, historian, literary critic, public speaker, committee member: all the bitsy ways you might have described it. ‘Public intellectual’ brought them together, neat and authoritative, and foregrounded this work of stimulating public discourse with knowledge and careful thought. I thought it was valuable, precious even. ‘She wouldn’t have considered herself an intellectual,’ Hill broke it to me.

But what did it matter what word you used? I wanted to follow the spindly trail of her thought. There was so much to say about Wright’s intellectual formation and family life that my book The Unknown Judith Wright (2016) concluded with her university years. In 2022 I anthologised Wright’s non-fiction for La Trobe University Press’s Australian Thinkers series. Judith Wright: Selected writings was, finally, an assertion of Wright as public intellectual.

This month, the Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB), is publishing its first entry on Judith Wright. When I was asked to write it, I felt all the dirty things a biographer feels: closer to their subject (spuriously), recognised, the weight of representing this ‘discordant’ life, as Philip Mead characterised it, and that relatively rare thing: a public, woman’s life. Pass me the stockwhip!

Tempering this was the knowledge that Wright had reservations about the biographical enterprise, and by now I did too. The ADB, a digital archive of entries dating back to 1966, is burdened by a historically heavy male weighting in both its subjects and authors. As well as this, it has maintained an encyclopedic approach to life writing, placing value on action and events, interventions in the public realm. It is not unusual to come across an older lengthy entry that mentions only in the final line that the subject had a wife of fifty years and five children, as if these were inconsequential to the rest of that life – public or not.

My intention was to represent Wright’s accomplishment – factually, clearly – and her formative relationships, collaborations, and their central role for her intellectually. Few other collaborators were as important as her mother. Literary critics and biographical accounts have tended to skate over this, if even noting what Ethel Wright put in train – through her action and her example. Ethel had been Judith’s first reader, each night, before she taught herself to read at aged four; the first and so enthusiastic reader of her poetry, and her first school teacher. Ethel wanted her daughter to be a writer. In Half a Lifetime, Wright had described her mother Ethel’s first hospital admission when she was seven as the ‘end’ of a world; Ethel’s death from influenza when she was twelve as the ‘end of my childhood’. It left her with a lifelong sense of precarity, loss, and urgency that sat beneath all else she did. In her writing across the decades, whether the topic was native wildflowers, language, or the conservation movement’s approach to Indigenous knowledge, the word ‘crisis’ recurred. It was a constant in all that movement.

Where Wright worried about the artifice of unity created by life writing, and the evasions sitting just below the surface of the text, it occurs to me that in the ADB her life looks cohesive and meant. Perhaps this smoothing over is what always happens with canonisation, in much the way Wright’s poetry was framed in more simple ways when it entered school curricula. Her life, like her poetry, has come to represent things beyond herself: themes, history’s arch, a ‘useful guide’ even. Still, here we have it, a woman’s life, its silver trail sealed.

This is one of a series of ABR articles being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment