- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

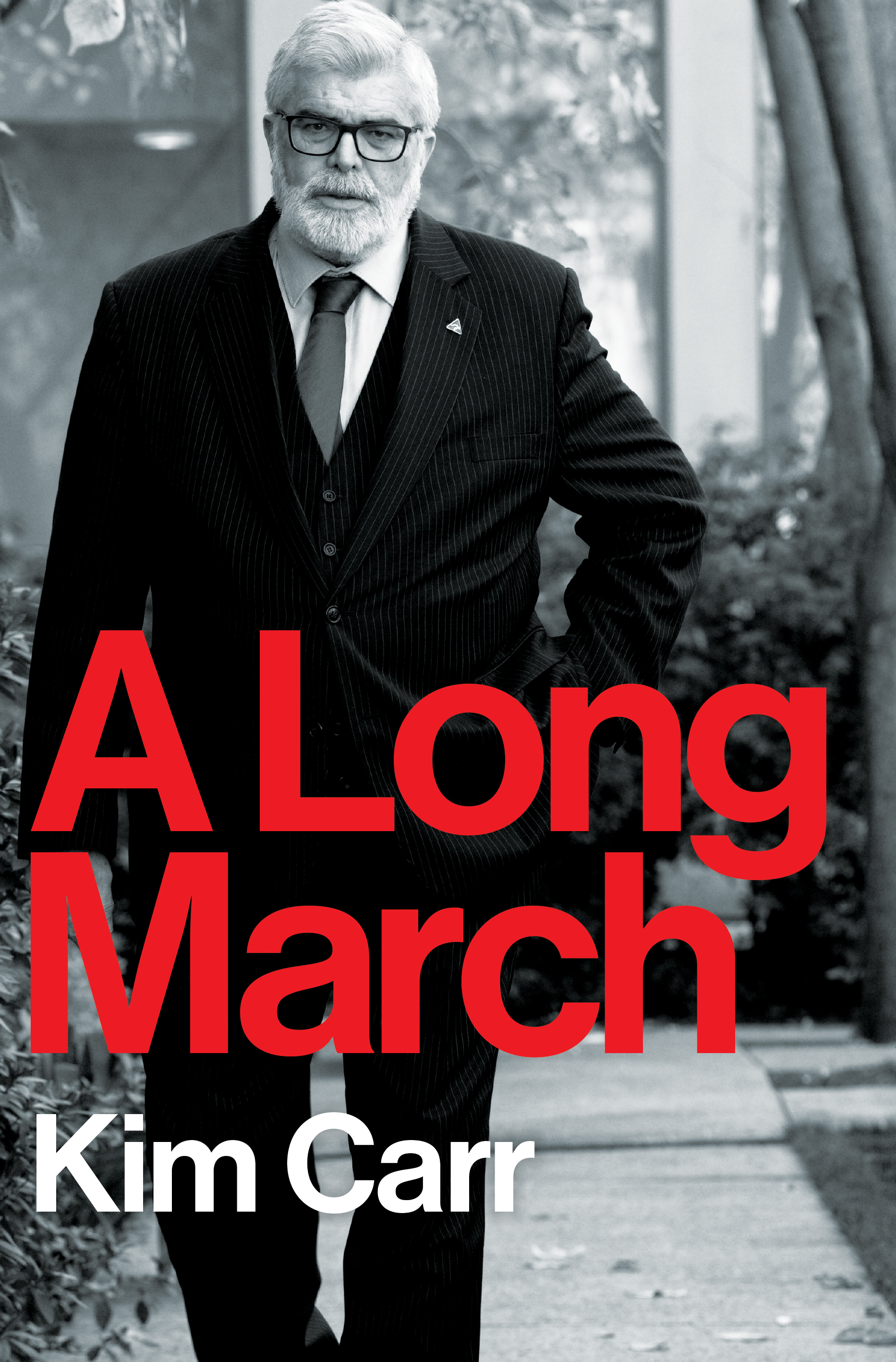

- Article Title: The bonfire of egos

- Article Subtitle: Kim Carr’s insightful, evasive memoir

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Criticisms first. Kim Carr’s insightful yet evasive memoir, A Long March, reads more like a short march. As a key left factional leader in the Australian Labor Party for the best part of forty years, the former Victorian senator squibs on details. He doesn’t explain the subterranean workings of the ALP; doesn’t fess up on the genesis of his feuds with the likes of Julia Gillard, Kim Beazley, Greg Combet, Anthony Albanese, and John Cain; doesn’t come clean on the part he played in the fall of the Gillard government in 2013; and doesn’t take his share of responsibility for the Rudd-Gillard-Rudd governments’ failure to implement his laudable industry policies. This book should be more revealing, much longer, and much more reflective.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Joel Deane review ‘A Long March’ by Kim Carr

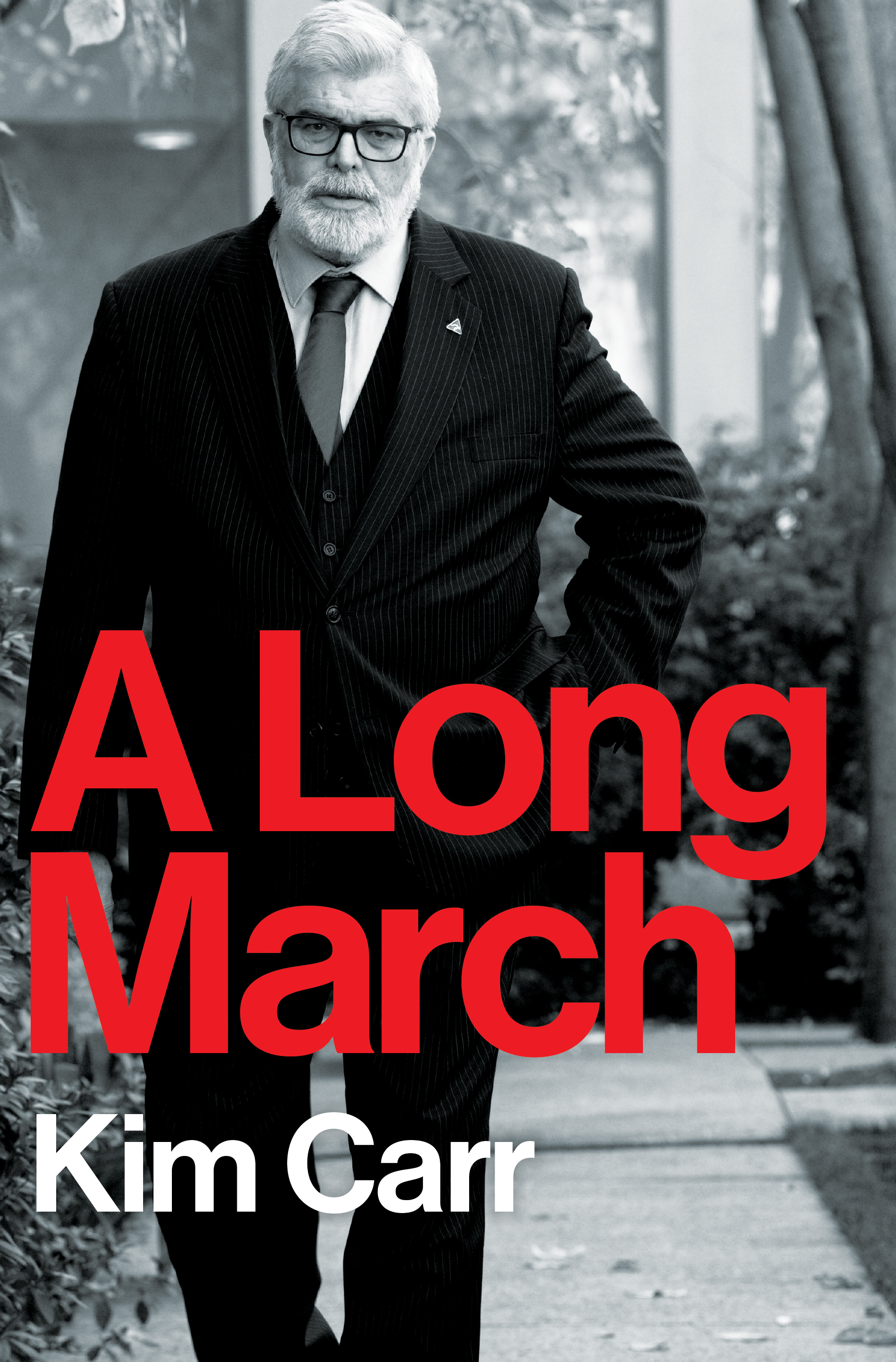

- Book 1 Title: A Long March

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $49.99 hb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781922979872/a-long-march--kim-carr--2024--9781922979872#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Numerous members of that government, including Gillard, Rudd, Combet, Lindsay Tanner, Wayne Swan, and Peter Garrett, have written firsthand accounts of the spontaneous combustion that burned the Rudd prime ministership, followed by the insurgency that destroyed the Gillard prime ministership. Scores of books have also been written about the key players and catastrophic events of those years. (Full disclosure: in April 2025, Melbourne University Press will publish a book I co-wrote with Jenny Macklin, another Rudd-Gillard minister.) Still, there is no definitive account of the bonfire of ambitions, egos, and, yes, vanities that shortened the life of a progressive government, inspired a decade of in-fighting by a conservative government, and, most importantly, broke faith with the Australian electorate.

The leadership coup of 24 June 2010 was a turning point in Australian politics – in all the worst ways. It showed that, collectively, the generation of politicians who rose to power in the aftermath of John Howard’s 2001 election win was either unable or unwilling to distinguish between personal ambition and the national interest. No wonder the electorate’s faith in Australian democracy is at its lowest ebb since the dismissal of the Whitlam government in 1975.

Julia Gillard and Kim Carr (photograph by John Woudstra, The Age, courtesy of Monash University Publishing)

Julia Gillard and Kim Carr (photograph by John Woudstra, The Age, courtesy of Monash University Publishing)

Somehow, progress was made despite the carnage. Rudd and Swan saved Australia from the worst of the global financial crisis. A raft of Rudd-Gillard social policy reforms, such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme and paid parental leave, survived the 2013 loss. And, although repealed by the Abbott government, the Gillard government’s carbon price mechanism, which tripled the tax-free threshold, still benefits every taxpayer. All of which makes it painful to imagine what more could have been achieved by a unified Labor government.

Carr understands the extent of the damage caused by the Rudd coup. His book opens by describing the ‘discomfort and creeping sense of dread’ he felt the night before the first of so many political thrill-kills. Carr was the factional player who brought Rudd and Gillard together – backing their 2006 push to replace Beazley and Macklin as leader and deputy leader, then forging the pact that Rudd would stand aside for Gillard after two terms as prime minister – but he was blindsided by June 24. More than a hundred pages later, he returns to Australia’s first (but not last) unseating of a first-term prime minister and concludes that the Rudd coup was the ALP’s fourth split. The first split was sparked by conscription during World War One, the second by the Depression, and the third by the Cold War. Carr writes:

These schisms had their roots in policies and the politics associated with those policies, but then inevitably took on personal dimensions … The difference in this split, however, was that … it was the personal antagonisms that came first. The beginning of this rupture came about chiefly because ambitious people did not like Rudd, so they banded together to bring him down and advance themselves.

This telling insight goes some way to explaining why the incendiary politics that led to the fall of Rudd, the rise of Gillard, then the pyrrhic return of Rudd still burns like napalm. We won’t know the hard truth of the Rudd-Gillard wars until all the players, including Albanese, are finished with active public life and the Cabinet records begin to be released in 2028. This much is clear: the leaders of the Rudd and Gillard coups disgraced themselves and their political party.

Which brings me back to Carr. His memoir is self-serving. Carr never misses an opportunity to undermine Gillard without spelling out the measures he and other left factional leaders took to block her attempts to win preselection, an impasse only broken in 1997 when a small number of left members broke away to back Gillard as the right’s candidate for Lalor. He sinks the boot into Combet and Beazley without revealing the source of the animosity; if you are curious, you can find the answer in Combet’s memoir, The Fights of My Life (2014). Likewise, Carr finds it ‘unfathomable’ that former Victorian Premier John Cain was ‘scathing’ about former Hawke government minister Gerry Hand in his memoir, John Cain’s Years (1995). This deflection is too cute. Cain was not scathing about Hand; he was scathing about Carr.

I am not cataloguing these evasions to prosecute a line against Carr. For the record, I have never been a member of any ALP faction and was not involved in the bastardry of the Rudd-Gillard years, although I have written speeches for Macklin, Shorten, and Gillard, as well as Rudd-supporter Chris Bowen. As for Carr, I have never met the man, though I interviewed him via phone while researching Catch and Kill: The politics of power (2015). Carr was an impressive subject: insightful, intelligent, blunt. In short, he struck me as a straightshooter who cared deeply for the cause of working people.

The Carr I interviewed is evident in A Long March. It is the work of a conviction politician who spent decades pushing against neo-liberalism within and without the ALP. It is also insightful on a wide range of political issues, such as Labor’s loss of ambition following Shorten’s 2019 election loss, the cowardice of Albanese’s small-target politics, the folly of AUKUS, the need for local manufacturing, and the danger of Labor’s disengagement from working-class workers. But it lacks the blunt attack of the Carr I heard about and interviewed – a factional player described to me, by more than one person, as one of the most important political players to come out of Victorian Labor since the fall of Whitlam.

As a result, the book was evasive when it counted. For instance, this is what Rudd, in Not for the Faint-Hearted (2018), said of Carr: ‘Unlike many in the caucus, I have always liked Kim. Often called Kim Il-Carr – a tongue-in-cheek reflection of his alleged North Korean sympathies and dictatorial leadership style – he was an old-fashioned Labor man from the hard left.’

That version of Carr is partly obscured in A Long March. This is still an important book worth reading, but it fails to demonstrate why Carr was so dominant for so long. That’s a pity: much as it is hard to forgive a self-indulgent caucus, it is impossible to trust an unreliable narrator.

Comments powered by CComment