- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Battles in Eurasia

- Article Subtitle: Intense global competition

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The title and cover of Great Game On tell us that a struggle is underway between Russia and China for supremacy in Central Asia. But by the time the reader has reached the book’s end, they are persuaded that China has already won and that there is more than just Central Asia at stake.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Nick Hordern reviews ‘Great Game On: The contest for central Asia and global supremacy’ by Geoff Raby

- Book 1 Title: Great Game On

- Book 1 Subtitle: The contest for central Asia and global supremacy

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $34.99 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9780522879667/great-game-on--geoff-raby--2024--9780522879667#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Raby takes this theory as his starting point, and if Central Asia is the hub around which the world revolves, then Afghanistan is in turn ‘the geopolitical hub of Eurasia’. Seen in this light, America’s withdrawal from Kabul marked the end of Western influence in the core of Eurasia: a retreat of global significance. But historical currents can be diverted by contingency; not only that, recently history itself seems to have been speeding up. Even in the brief interval since Raby’s book went to press, events have changed the way people will read it.

It is well known that recent decades have seen a shift in power from the United States to China, but less well known that there has been an almost equally important shift from Russia to China. Throughout most of modern history, Moscow lorded it over Beijing, leaving an embittered history of relations between the two Eurasian giants, the biggest bone of contention being Outer Manchuria, the vast territory bordering the Sea of Japan that Russia seized from China in the mid-nineteenth century. This is now changing, and the shift in power from Russia to China has been dramatically accelerated by the war in Ukraine. While Europe now views the Kremlin as a violent, unconstrained menace, China sees it as an old adversary diminishing to the level of a mendicant client.

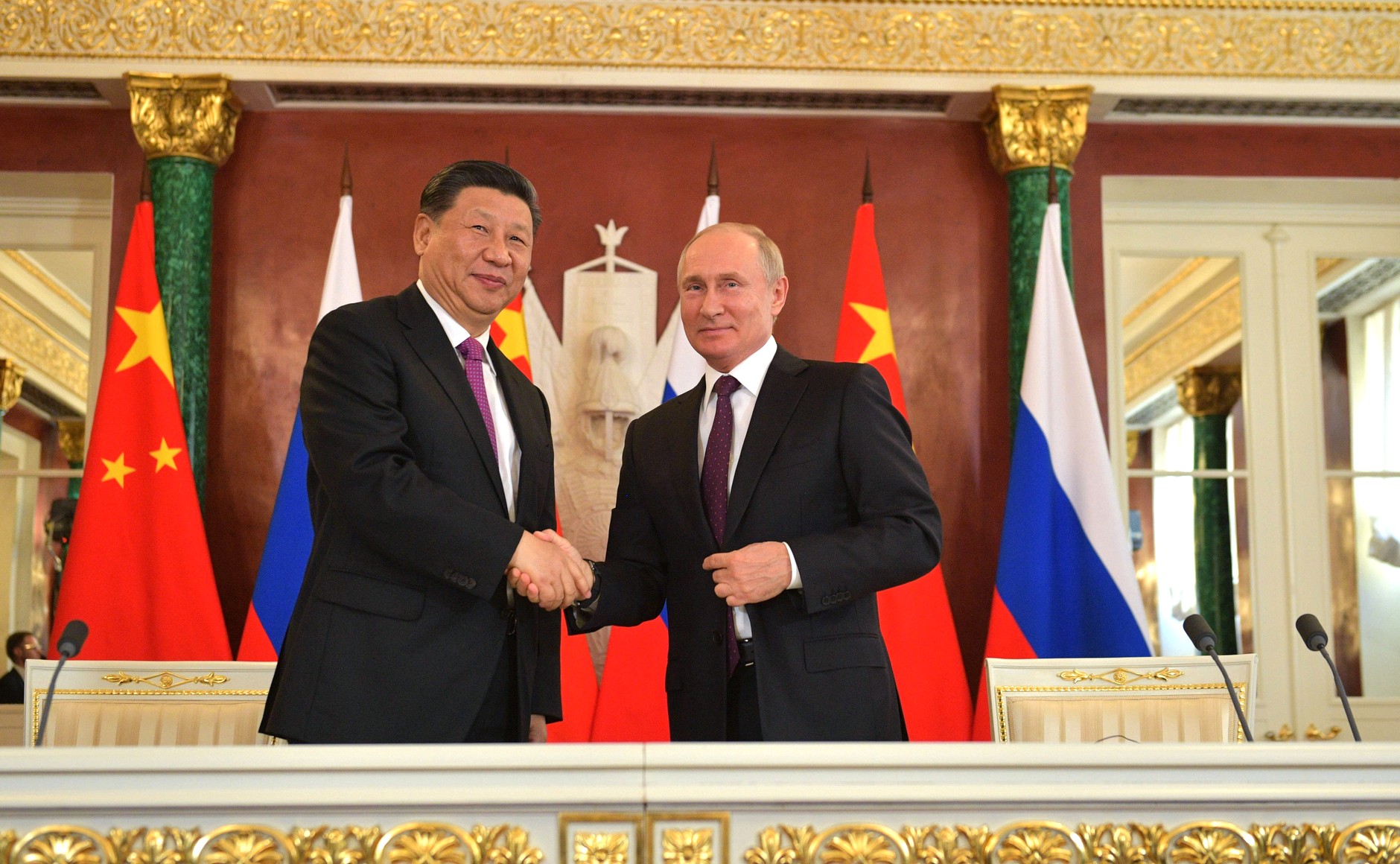

Under Vladimir Putin, post-Soviet Russia rejected a rules-based global order, for example by invading Georgia. Announcing a ‘pivot to the East’, Putin turned away from the West and towards Beijing, beefing up Russia’s military relationship with China. Even so, it seems he did not forewarn President Xi Jinping of his 2022 assault on Ukraine, something which would not have gone down well in Beijing. China had good relations with Kiev and Putin’s attack violated the principle of ‘non-interference’, a key plank of Beijing’s foreign policy. Xi will also have been given pause by the relative strength and unanimity of the Western response, including the sanctions imposed on Moscow, China being more integrated into the global economy, and thus more exposed to sanctions, than is Russia.

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, 2019 (Kremlin via Wikimedia Commons)

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin, 2019 (Kremlin via Wikimedia Commons)

Nevertheless, Beijing has refrained from condemning Moscow’s aggression and has helped it evade sanctions by supplying the Russians with warlike materiel – machine tools and dual-use technologies – often through third parties in Central Asia. China has also been happy to become (along with India) the major customer for cheap Russian oil, heavily discounted because of sanctions. Overall, however, Beijing’s support for Moscow has been comparatively restrained, though sufficient for NATO to label China a ‘decisive enabler’ of Russia. In the long term, Putin’s Ukraine adventure can only weaken Russia’s position vis-à-vis China, hastening Beijing’s emergence as the dominant power in Eurasia. Moscow now has nowhere else to turn.

Well, perhaps not entirely – and this is where contingency rears its disturbing head. In October 2024, North Korea, already a major supplier of munitions to Russia, sent its troops to join in the Ukraine war on Moscow’s side. This prompted Washington to give Kiev permission to fire American tactical ballistic missiles into Russia, sparking headlines about World War III. In exchange for its troop deployment, North Korea reportedly received missile technology that will enable Pyongyang to improve its nuclear arsenal, which now threatens the continental United States. Again, these are not developments that Beijing would have welcomed: above all else, China desires stability on the Korean Peninsula, and an emboldened and better armed Kim Jong Un is the very incarnation of instability.

The aim of the current Great Game is not to seize territory as such, but rather to become the dominant influence in the five former-Soviet, mostly Turkic-speaking countries of Central Asia, to which we might add Azerbaijan and Afghanistan. The Central Asian republics have proved relatively adept at playing Russia and China off against each other, reducing their Soviet-era dependence on Moscow in the process. To Beijing they represent a source of energy exports and the prospect of transport corridors to Europe that avoid the hazards of both maritime chokepoints like the Red Sea and of land routes through Russia, whose potential vulnerability have been underlined by the Ukraine War. The Central Asian countries also have booming, relatively well-educated populations, which makes them an attractive destination for Chinese investment.

Both China and Russia have a major security interest in the region, to contain the fundamentalist threat from groups like Islamic State Khorasan (IS-K) and, in China’s case, to stop that threat spilling over into its Xinjiang region, with its restive Muslim Uyghur population. Beijing’s diplomacy in the region is directed to that end: in 2022, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan voted in the United Nations with Beijing to deflect criticism of China’s human rights record in Xinjiang.

In November 2024, Afghanistan’s Taliban had a rare positive news announcement to make: a goods train had arrived in the northern city of Mazar-e Sharif direct from China via Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. This seems to bear out Raby’s contention that the American withdrawal from Afghanistan left a vacuum that China would automatically fill. But this rests on the assumption that the Taliban will be able to guarantee internal security, a precondition for Chinese development projects such as the massive Mes Aynak copper mine just outside Kabul. Instead, not just IS-K but ethnically based resistance groups are now chipping away at the Taliban’s rule, launching attacks even in Kabul itself. Afghanistan-based groups have carried out cross-border attacks on Chinese personnel in Tajikistan.

Here again, contingency intrudes because the United States is just about to re-invade Afghanistan: we know this because president-elect Donald Trump said so. Speaking of the key Bagram airbase north of Kabul in September 2024, Trump said ‘We wanted to keep [Bagram] because of China ... It was only an hour away from China’s nuclear facilities ... I promise you we’re going to get it back.’ His statement might not have registered much in the West, but it certainly did in Kabul and presumably in Beijing. So a renewed American involvement in Central Asia joins the long list of known unknowns about the second Trump administration, which range along a spectrum of likelihood from abandoning Ukraine and axing AUKUS to pulling out of NATO.

Geoff Raby’s bottom line? ‘The world has entered the most intense phase of global competition, short of outright military conflict, ever experienced.’ And that was before Donald Trump started throwing spanners in the works.

Comments powered by CComment