- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Leaves of brass

- Article Subtitle: A tale of simple good fortune

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

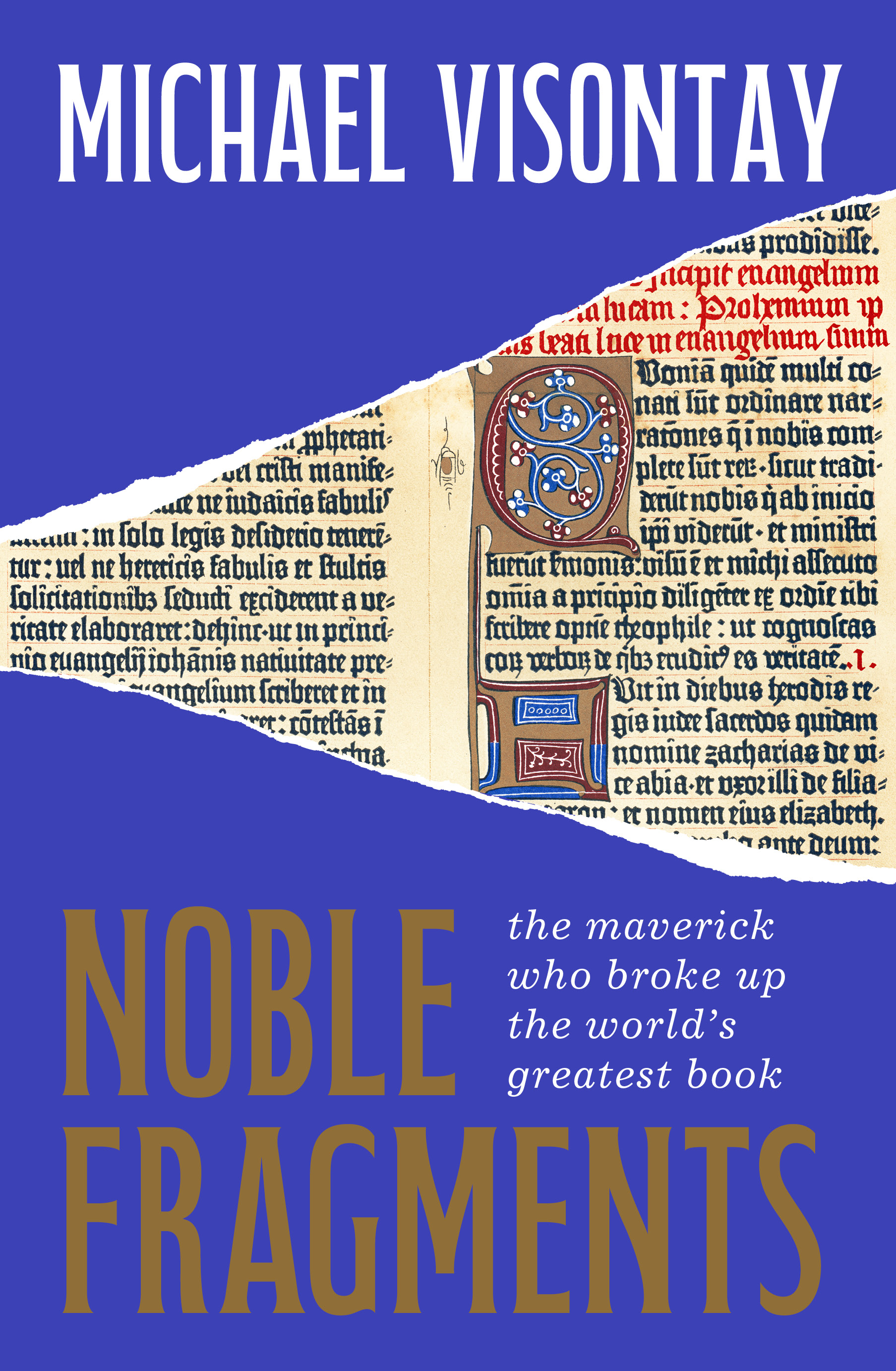

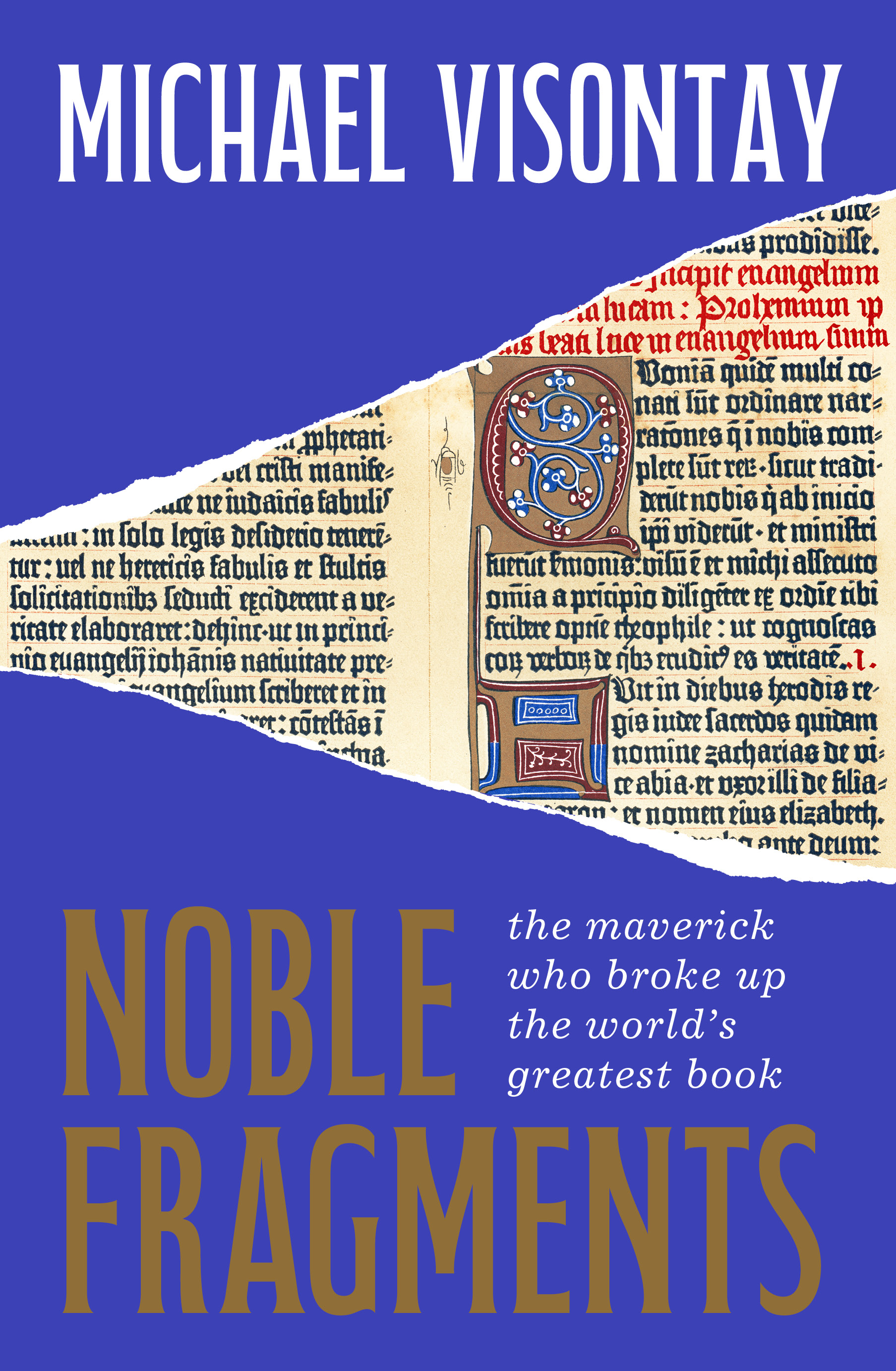

Michael Visontay’s Noble Fragments is about second chances, serendipitous connections, and simple good fortune. At its heart is a young man fleeing bankruptcy in Hungary who reinvents himself as a rare-book dealer in the United States and his impact on the Visontay family, which had survived the horrors of the Holocaust to become a classic example of Central European migration to Australia after World War II. The book deftly links an intriguing story about bibliophiles and the addiction that is rare-book collecting with the poignant tale of a traumatised son’s devotion to his father.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jason Steger reviews ‘Noble Fragments: The maverick who broke up the world’s greatest book’ by Michael Visontay

- Book 1 Title: Noble Fragments

- Book 1 Subtitle: The maverick who broke up the world’s greatest book

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $36.99 pb, 266 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781761380822/noble-fragments--michael-visontay--2024--9781761380822#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

Visontay, a former Sydney Morning Herald journalist, made the dream discovery for a writer with an inquisitive mind: a long-forgotten strongbox that revealed family secrets and a connection to Gábor Weisz, a Jewish Hungarian who changed his name to Gabriel Wells when he arrived in the United States in the early 1890s. Wells had ‘an adventurous streak and entrepreneurial flair, a combination that would become his calling card in life’. He spoke eight languages and found a mentor in William James at Harvard. Wells moved into rare-book dealing in New York and discovered a new role ‘“revising” print runs with new covers’. It proved lucrative, so much so that he could set up an office on Book Row – East 23rd Street. Rivalry among the dealers was intense as powerful industrialists began to assemble collections to ‘show the world that wealth and taste were not mutually exclusive’. But there was plenty of money to be made in the years up to the crash of 1929.

Visontay portrays the Golden Age of American book collecting as fiercely competitive, dominated by figures such as George D. Smith and Abraham Rosenbach. They went in hard to get their clients what they wanted, whether it was Shakespeare’s First Folio or the holy of holies, a Gutenberg Bible. The celebrated Bible was printed by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany in two volumes in 1455 using his innovative method of moveable metal type and his unique oil-based ink. It was a work of great beauty and quality, consisting of 643 leaves with two pages on either side of each leaf. Today, forty-eight copies survive, but only twenty are complete.

In 1921, Wells bought one of those incomplete Gutenbergs. As it was missing fifty-three leaves, he took the extraordinary decision to split the two volumes into individual leaves – the titular ‘Noble Fragments’ – keeping some together in the discrete books in which they appeared in the original, bind them in leather, and, to add value, commission an essay by bibliophile Edward Newton. Visontay devotes several pages to differences of views among experts concerning Wells’s tactic: was it cultural vandalism or some sort of democratisation?

Wells flogged them within a couple of years, making a tidy profit, and, as Visontay says, probably making more than the tycoons paid for their complete copies. All sorts of people pounced on the fragments. The first was American architect and social-housing pioneer Isaac Stokes, who snapped up the Ten Commandments from Exodus, while composer Jerome Kern, who admitted to being ‘enslaved’ by books, bought a leaf from Deuteronomy. There are eleven leaves in Australia, in universities, public libraries, and private collections. Businessman Kerry Stokes has two – from St Luke and Proverbs.

What has this all to do with Visontay? In 1944, his Hungarian grandfather Pali, who ran a delicatessen, was taken away with other men from the Gyöngyös Ghetto. Pali’s wife, Sara, and son Ivan were transported to Auschwitz, where two days later Ivan stumbled across his mother’s body in a pile of corpses. ‘I have tried many times to imagine the horror he must have felt,’ Visontay writes, ‘a 14-year-old boy confronted by a scene of such personal devastation that he was rendered mute.’

Pali and Ivan were reunited in Budapest after the war and rented a room from Olga Illovsky, a Jewish woman who had managed to avoid transportation to Auschwitz, unlike almost all of her Hungarian family. She also happened to be Gabriel Wells’s niece. A year later, to Ivan’s dismay, Pali and Olga married, ‘most likely a pragmatic decision by two people to rebuild their lives’.

In a matter of months, however, Wells was dead and Olga came into a decent inheritance from Wells. After escaping to Austria, the three Visontays found their way to Sydney in 1952, Wells’s money allowing Pali to return to what he knew best: running a delicatessen. But when Olga died less than two years later, she was buried on the other side of the city with no mention of Pali and Ivan on the tombstone: ‘Neither of them wanted to claim her,’ Visontay writes, and adds later, ‘her name never mentioned, her role in the family’s rebirth never referenced. She was a non-person.’

Noble Fragments is, then, a curious mixture of biblio-history and family memoir linked by the sad figure of Olga. Visontay is dogged in tracking the history of the leaves that Wells excised – most of which are now in public institutions – and the fate and whereabouts of those forty-eight intact Gutenberg Bibles around the world.

However, there are a few individual Noble Fragments still available from dealers – for about US$150,000 – and the only complete book from the Bible, Haggai, can be had from a London dealer for US$450,000.

Ivan survived the Holocaust thanks to a brave Czech doctor, Ludovic Pollak, luck, and, ironically, a decision taken by Josef Mengele. While Ivan’s is a very different history from the one Rachelle Unreich tells about her mother in the memoir A Brilliant Life (2023), in both cases their survival owes much to good fortune. Visontay tells Wells’s story and that of his own family straightforwardly with insight and sensitivity.

Comments powered by CComment