- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Left, right, back again

- Article Subtitle: Memoir of a public intellectual

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

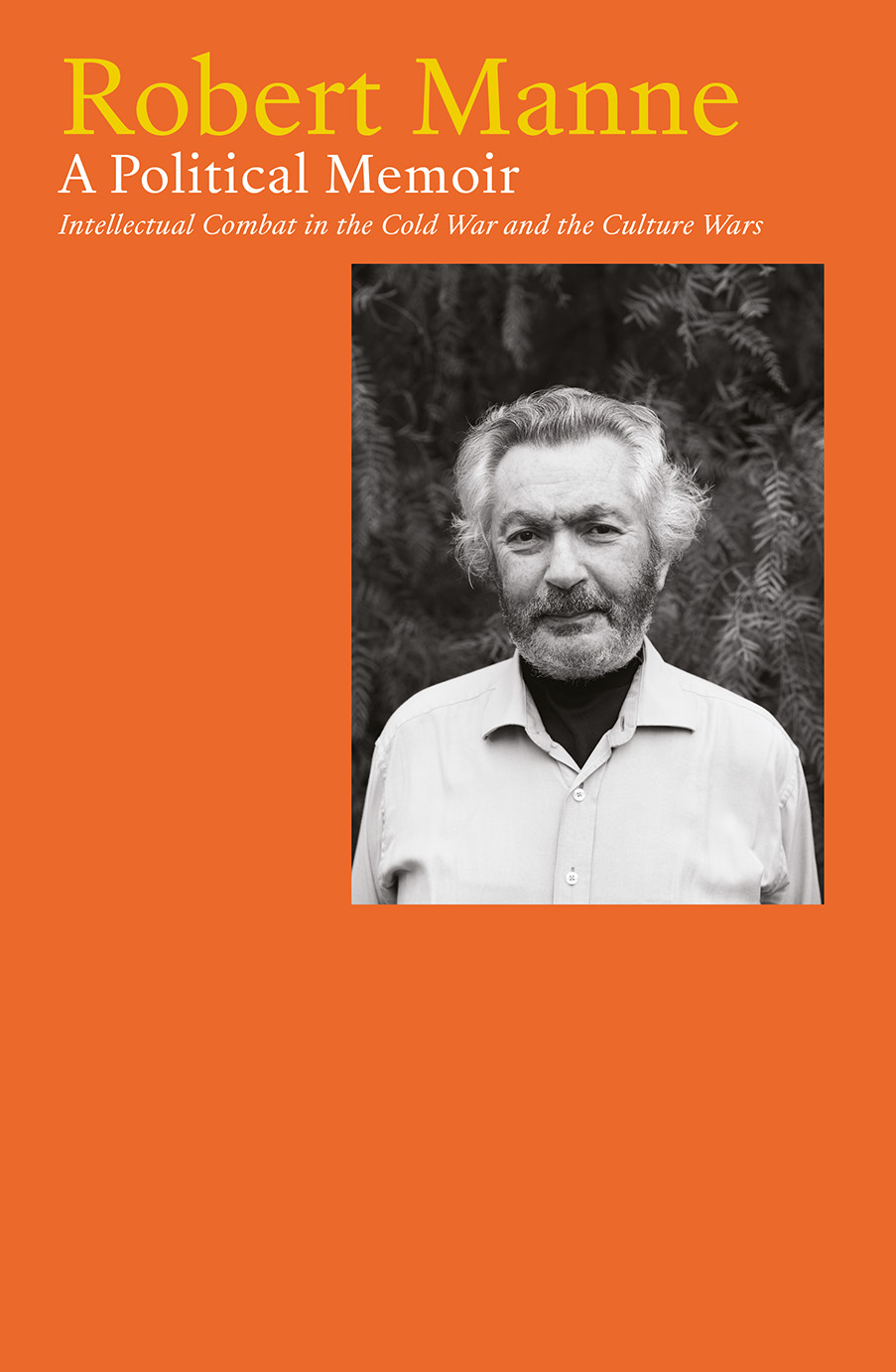

Raimond Gaita is quoted in his close friend Robert Manne’s new memoir as saying that a ‘dispassionate judgement is not one which is uninformed by feeling, but one which is undistorted by feeling’. That distinction points to one of the many attractive qualities of A Political Memoir: Intellectual combat in the Cold War and the culture wars.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Frank Bongiorno reviews ‘A Political Memoir: Intellectual combat in the Cold War and the culture wars’ by Robert Manne

- Book 1 Title: A Political Memoir

- Book 1 Subtitle: Intellectual combat in the Cold War and the culture wars

- Book 1 Biblio: La Trobe University Press, $59.99 hb, 496 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781760645069/robert-manne--robert-manne--2024--9781760645069#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

The fate of Manne’s family provides the personal dimension. His paternal grandparents, and an uncle, attempted suicide in Vienna in May 1938; his grandmother succeeded. Her husband survived, only to be murdered in a concentration camp. Manne’s maternal grandparents also perished at the hands of the Nazis, in Poland.

Manne’s father, an intellectually inclined furniture maker, lost his Melbourne business and died when Robert was still very young. The boy became the carer of his invalid mother during his teenage years. She died when he was eighteen. There were other relatives around, including a much-loved Uncle Hans, who worked in a delicatessen at the Prahran Market: ‘One of our joint pleasures was walking together with me standing on his feet.’ While there are many expressions of love for family in this memoir, Manne writes elsewhere of the pain of ‘alone-ness’. There is something both self-contained and solitary in several of the moments of introspection that punctuate the book.

Manne has lived with cancer for many years and had his larynx removed in 2016, greatly reducing his ability to speak. The memoir, written at the suggestion of his friend and long-time publisher Morry Schwartz, will be essential reading for anyone interested in what has happened to politics and ideas in this country since World War II.

For me, its most important aspect is its demonstration of what the life of a European intellectual could be in this country in the decades around the turn of this century. I use the term ‘European’ in a very specific sense. Manne is, after all, an Australian patriot. He was born here and ultimately chose to live here. His career has been devoted to influencing this country’s public life.

This sophisticated intellectual explains his attachment to Australia in simple terms: in an era when dictators were seeking to remove their ideological and racial enemies from the world, Australia gave his mother and father sanctuary. Manne’s intellect and sympathies have been most consistently engaged when he has contextualised the controversies of his own time in the triumph, and later defeat and collapse, of totalitarianisms cultivated in the blood-soaked Europe of his parents and grandparents.

His indignation at the left’s whitewashing of the Khmer Rouge of Kampuchea (Cambodia) was fuelled by his outrage at the earlier denialism of the defenders of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin. His indignation with the Australian radical journalist Wilfred Burchett was founded on Burchett’s collaboration in the squalid history of twentieth-century communist totalitarianism – and his lying about it. And it was Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963) that shaped his thinking on the genocidal character of the policy of Aboriginal child removal. There is a sensibility rooted in European history and politics at work here, which makes it no less Australian for that.

In a book that would have appeared when Manne was in his final years at school, Donald Horne argued in The Lucky Country (1964) that Australian intellectual life, such as it was, lacked ‘serious consideration of human destiny, or … prolonged consideration of the Australian condition’. Horne felt that Australia’s intellectuals ‘shelter from the major challenges and ideas of the twentieth century’. I am not sure that was true in 1964; it is certainly untrue of the life of the mind pursued by Manne in the six decades since. In one of those lists that appear from time to time in Australian newspapers, Manne was rated the nation’s leading public intellectual.

Manne’s early trajectory would not have indicated any imminent departure from the pathway of conventional academic work. There was undergraduate study for an arts degree, during which time he came under the influence of two redoubtable academic-intellectual-activists: Frank Knopfelmacher, a Czech Jew refugee, migrant, and British-educated psychologist; and Vincent Buckley, Irish Australian, Catholic, poet, and literary critic. Manne paints the intellectual and political vibrancy of the University of Melbourne of the 1960s in rich colours. ‘If any current students read this book,’ he says, ‘I hope it will help them understand what universities in Australia once were, what they no longer are, and what they might be again.’

His version of 1960s university life is indeed a stark contrast with the joyless, soulless apparatus the corporate, neo-liberal university has largely become. His was a place where academics and students – not all, but many of them – fought the big Cold War political battles of the era, forged lifelong friendships, and sparked enmities that were still playing out more than half a century later – as in the case of Manne’s with Gerard Henderson.

At Oxford, Manne enrolled in the degree that many of the bright young Australian men completed: a bachelor of philosophy. It was tough, but he thrived. His early work as a scholar was conventionally academic: the study of British foreign policy in the 1930s. But Manne was seeking a wider audience, and he wanted a role in public life. He could do neither with specialised studies of the kind that Kingsley Amis famously satirised in Lucky Jim.

Manne has shown that he is no slouch with the close archival research of the orthodox political historian, as in his accessible, ground-breaking study The Petrov Affair (1987) – still, decades after its publication, the standard, indispensable work on its subject. Manne’s career mainly headed in other directions; as the author of articles for newspapers and magazines intended to appeal to intellect and conscience; as the editor of the conservative magazine, Quadrant (1989-97), before his bitter falling-out with editorial board members and the magazine’s subsequent journey into irrelevance; and as the author or editor of books or extended essays addressing topics as diverse as the controversy over Helen Demidenko/Darville’s Holocaust novel The Hand That Signed the Paper (1994), Rupert Murdoch’s The Australian, Julian Assange, Islamic State, and climate change.

Put simply, Manne’s politics moved from the left – as a student at Melbourne University – to the right, and then back left again. But to express it that way says much less than is needed. There are strong continuities across these apparent shifts of ideology and perspective in his commitment to a liberal rationality informed by an acute moral sense.

All the same, his trajectory has been relatively unusual among Australia’s conservative liberals, who were more likely to make a comfortable journey from cold warrior to culture warrior; or, in the case of the most influential of them, Bob Santamaria, from anti-communist to late-life critic of capitalism. Manne was himself a sometime opponent of the more extreme versions of economic rationalism, now known as neo-liberalism. But his career is interesting not least for its lack of economic wonkishness in an era when senior members of the economics profession often looked like being raised to some local equivalent of the Order of the Garter.

Manne has been concerned with politics, more than with policy; he turned down an early-career job offer writing speeches for Andrew Peacock. Kevin Rudd eventually played a part for Manne, who admits to a hatred of John Howard, that was akin to the role that Gough Whitlam played for many of those who were Manne’s ideological opponents in the 1970s. Rudd ultimately disappointed Manne, as he did most of us. Manne has normally kept several paces away from conventional party politics.

Manne remarks often that some controversy or other in which he was engaged during his career made him ‘angry’. I, too, often felt myself becoming angry when reintroduced to members of the rogues’ gallery who did so much to disfigure the nation’s public life at the turn of this century, with their denialism over Indigenous history, refugee injustice, and climate change. Some of these who appear on the now lengthy list of Manne’s enemies, or former friends, will presumably dislike his characterisation of them and their behaviour. But anyone looking for a book that would be a salacious exercise in score-settling will find their hopes confounded.

Manne’s politics, whether of left or right, have lacked a partisan, tribal character, reflecting a rather old-fashioned liberal commitment to civil, rational, and open debate as a driver of progress. I was struck by the number of times that he acknowledges having adopted a position that he would later modify or abandon.

In Australia, especially for the right, that is a clear sign of weakness. A better view might be that it is an intellectual courage and moral seriousness that have become increasingly hard to find in this nation’s public life.

Comments powered by CComment