- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Chronicle and saga

- Article Subtitle: The current of social change in South Australia

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Marian Quartly’s ancestors were of ‘the middling sort’, a term used by historian Margaret Hunt to describe ‘people who were neither wage labourers nor gentry’: artisans, shopkeepers, skilled tradesmen, yeoman farmers, and the like. This class of people, says Quartly, ‘shared values and expectations that were shaped by the dangers of the commercial world; they were temperate, prudent, proud of their independence’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kerryn Goldsworthy reviews ‘The Middling Sort: A South Australian family history’ by Marian Quartly

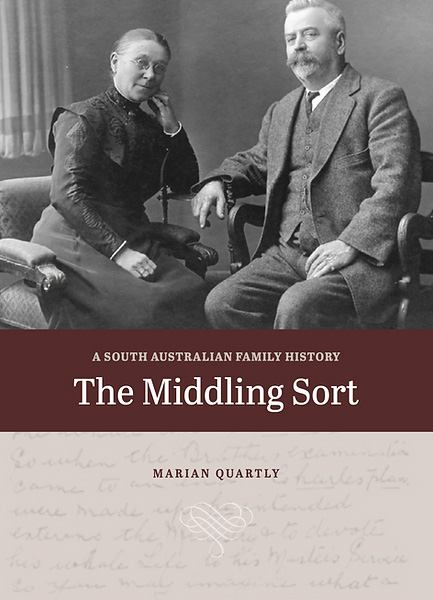

- Book 1 Title: The Middling Sort

- Book 1 Subtitle: A South Australian family history

- Book 1 Biblio: Marian Quartly, $45 hb, 188 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

What it does claim, and this is amply justified by the stories it tells, is spelt out by Quartly at the end of the book: ‘I am not claiming that my family members were representative citizens of South Australia. I am claiming for them and for others like them – middle-class citizens – a significant role in making South Australian history.’ This is borne out by the stories of civic-minded family members who were active in the building of community: who became councillors or teachers, who bought modest parcels of land, founded committees, and made improvements to South Australia’s capital city and its new towns.

The practice of researching one’s own family history gets easier all the time. Anyone with patience and enthusiasm can do it, and when they have done it, self-publication is now available to them as an option if they want it produced as a book. Relatively few people, however, can do it well, or in full and accurate understanding of sources and their reliability, or in a form that anyone else apart from family members might want to read – and sometimes not even family members.

Quartly has spent her working life as a professional social historian and scholar, and her book reflects as much in both its readability and its reliability. Where there is a scarcity of material, she says so; where she is speculating rather than recording, she makes that clear; the endnotes are thorough and meticulous. Self-published it may be, but it’s a well-designed, well-bound, copiously illustrated hardback, with family trees that help the reader to follow the maze of individual histories, and with family photos that flesh out and enliven their stories.

The bad news, and there is some, is that in what seems like an attempt to kill with one stone the two birds of chronicle and of saga, this book can be a frustrating read. A family chronicle is one thing: its whole reason for being is to provide as many facts as possible. But a family saga, written for a more general readership than family members or fellow scholars tracking down facts, needs both forward movement that pulls the reader along through the story, and a primary focus on individual characters and fates.

To some extent, this book has both that narrative tension and those vivid portraits, but it also seems that Quartly has included every fact she could find about each of the many family members and ancestors whose stories make up this book, sometimes going back as far as the early eighteenth century and tracing ‘all the families whose lines would be linked by the marriage of my parents’. Most of the recorded facts about individual lives of ‘the middling sort’, as they appear in newspapers and archives and other such records, are to do with either modest amounts of money and property or minor court cases, and that can make for laborious reading.

As source material goes, letters and oral histories and family lore are all as important here as the kind of detail that made it into the newspapers and the public archives in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries at all, much less the feats and failures of explorers and political leaders. Quartly’s project of writing a book about the making of a society as well as about the making of a family fits the small details of individual lives into the larger pattern of a ‘middling sort’ in society. ‘The immigrants attracted to the colony [of South Australia] were more literate, more skilled, and more married than those drawn or dragged to the convict colonies. The society they created was a “topped-and-tailed” version of British society.’

Many of her family members chose to emigrate by taking advantage of South Australia’s scheme offering free passage to the right sort of new citizen. In a plan that amounted to a form of social engineering, it imposed strict age limits, and it favoured married couples and nuclear families with no moving parts. Sometimes this emigration scheme had unintended consequences. Quartly writes of her great-great-grandfather Titus and his second wife, Mary: ‘The couple’s decision to marry was almost certainly related to their decision to immigrate: it was only as a married couple that they qualified for the assisted passage.’ It’s an ominous sentence, containing a nascent world of hurt.

Certainly, this family history features more than one unhappy marriage, including the one that gets a chapter to itself. ‘An Unhappy Marriage’ tells the tale of Quartly’s paternal grandparents and the intergenerational tensions resulting from their unwise coupling. Their son Gordon, Quartly’s father, ‘never spoke about his own life, his family or his family’s history … he was bitterly angry with his father’.

In researching the family and finding some explanations for her grandfather’s shortcomings, Quartly dedicates the last chapter to her late father. But the book as a whole is dedicated to her great-aunt, the magnificently named Ruby Emma Minlaton Quartly. Ruby was the proud owner of a family heirloom, a teaset purported to have been given to her grandfather by no less a personage than Sir John Franklin, then the governor of Tasmania, who would later perish heroically while exploring the Arctic wastes.

In providing a tangible link to the recorded past, even if only in the mythic regions of family lore, Auntie Ruby’s teaset gave the teenage Marian of 1957 a ‘sense of belonging to national history’. But she became a social historian of a kind for whom ‘Australian history as it is written today … takes affection and fear and religious experience and family violence seriously as historical phenomena’, and in this family portrait she demonstrates how all of those intangibles, one person and one family at a time, can affect and be affected by the currents of social change.

Comments powered by CComment