- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bearer of ideas

- Article Subtitle: A Fabian’s consequential life

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I first encountered Race Mathews in the early 2000s, around the time of the publication of my biography of Jim Cairns. He struck me as reserved and cerebral, but generous. As national secretary of the Australian Fabian Society, he invited me to deliver a talk about the biography at the Melbourne Trades Hall. Following Cairns’s death in late 2003, Mathews initiated a Jim Cairns Memorial Lecture as a joint endeavour between the Fabian Society and several university ALP clubs. What struck me about this was that Mathews and Cairns had been from different wings of the Labor Party, the former probably the most fervent disciple of Gough Whitlam, a philosophical and leadership rival to Cairns, and yet here he was helping to preserve the memory of Cairns. It suggested a refreshing ecumenicalism, an open-minded, enquiring spirit.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Strangio reviews ‘Race Mathews: A life in politics’ by Iola Mathews

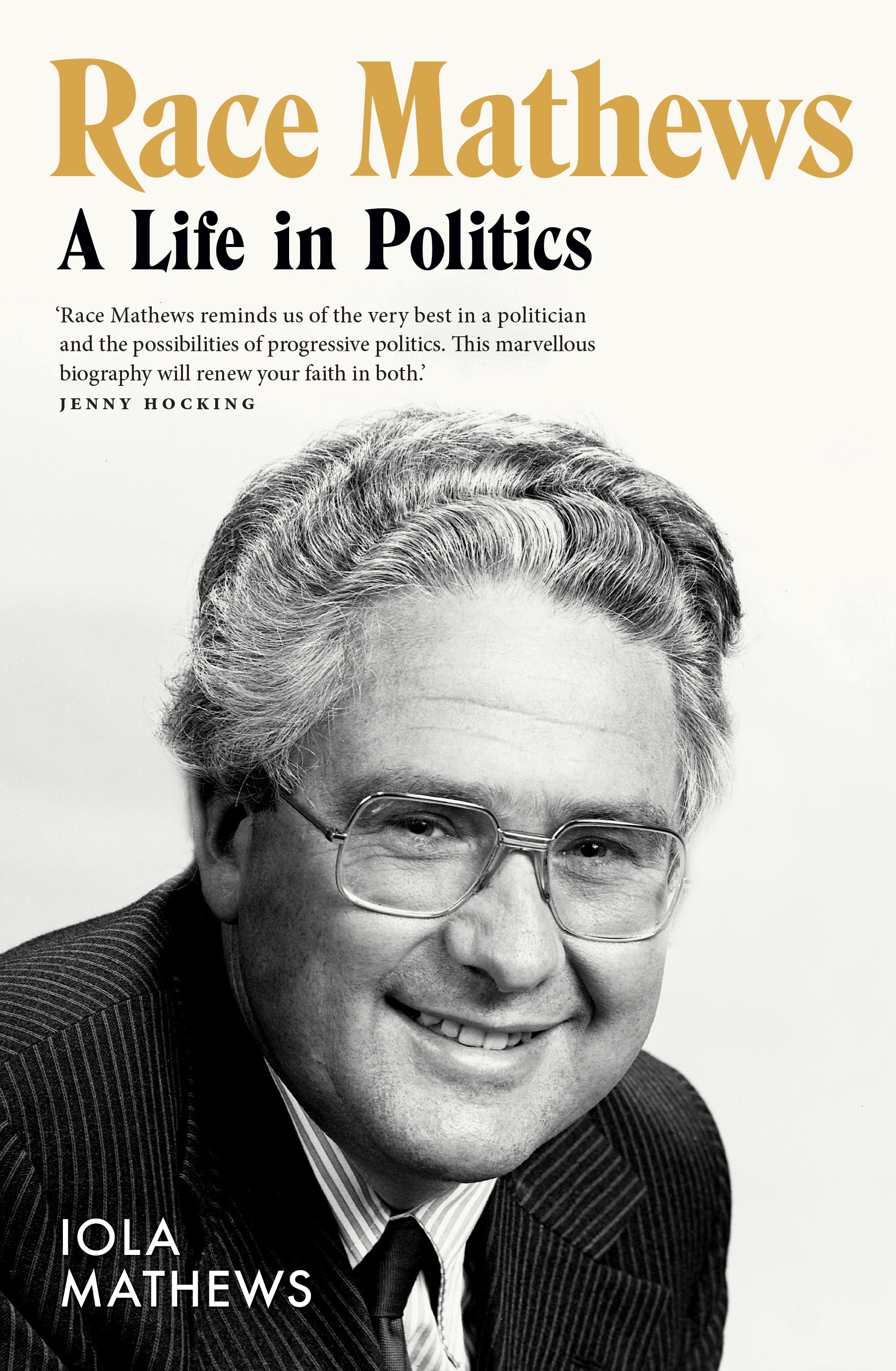

- Book 1 Title: Race Mathews

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life in politics

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $39.99 pb, 367 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The relationship between biographers and subjects is endlessly fascinating, endlessly complex and variable. Race Matthews is distinctive as a wife’s account of her husband but also because the first four chapters dealing with Mathews’s early life up until the age of twenty were drafted by him in his early eighties, before failing memory and eyesight forced him to abandon a memoir. Iola bravely decided to complete the task, aiming to preserve, as much as possible, his voice with quotes from his speeches, letters, books, and interviews (a 2014 oral interview by Garry Sturgess housed in the National Library of Australia is an especially fertile source). The transition is not completely seamless, and the opening chapters, which reveal a keen memory and flair for expressive detail, suggest what has been lost. Yet Iola’s account persuasively evokes the essence of Mathews: his intellectual curiosity. From a young age, he was an omnivorous and voracious reader, as well as passionate about other cultural forms, including film and music. Those habits never faltered. Mathews has exulted in the life of the mind.

By the early 1960s, Mathews had entered into the lion’s den of Victorian Labor politics. Together with other future ALP heavyweights, such as John Cain Jr and John Button, he hurled himself into the cause of reforming the party, a Frankenstein creation of the 1950s split, and a moribund outfit dominated by left-wing industrialists who equated virtue with disdain for political power. Those activities brought Mathews into the orbit of soon-to-be federal leader Whitlam, nemesis of the Victorian Labor ‘junta’. He remembered his time as Whitlam’s principal private secretary between 1967 and 1972 as the apotheosis of his public career, reflecting many decades later of his boss: ‘I was in awe of him, and I loved him.’

In a small team of close comrades that included revered Labor speechwriter Graham Freudenberg, Mathews played a leading role in policy development. He built and harnessed networks of expertise, while his own imprint was greatest on school education funding policy. Its reasoning was cogent and elegant, designed as a virtuous circle of good politics and policy. With the Menzies government having entered the Commonwealth into the field of funding non-government schools, Labor’s traditional opposition to state aid had become politically unsustainable. If the party did not respond, Catholics would continue shifting their voting allegiance to the Liberals via the bridge of the Democratic Labor Party. Besides, there was an equity imperative to assist underprivileged Catholic schools in industrial working-class suburbs. However, state aid could not be restricted to Catholic non-government schools, since that would invite a sectarian backlash. Yet crucially, while accepting the principle of Commonwealth funding support for a multi-stream school system, Mathews was adamant that the sacrosanct objective was that the public sector ought to be equal, if not superior, to the non-government education sector.

Mathews became one of Labor’s class of 1972, winning the Melbourne electorate of Casey when Whitlam became Labor’s first prime minister since 1949. He came to regret that move. As a novice backbencher and parish-pump local member in a marginal seat, he was isolated from the centre of power in the Labor government. He especially lamented his lack of influence when, in order to get the necessary legislation through the Senate, Whitlam cut a deal with the Country Party under which some funding was preserved for the wealthiest private schools, despite the recommendation of the government-appointed Karmel Inquiry that funding be phased out. The deal was the beginning of a rot, egregiously compounded by Whitlam’s prime-ministerial successors, Labor and non-Labor alike, that half a century on has resulted in Australia’s tangled, compromised, and scandalously inequitable school funding arrangements. It is an instance of the best intentions having unintended consequences.

After losing Casey in the anti-Labor landslide of 1975, Mathews initially aspired to an early return to Canberra, coveting the safe ALP seat of Batman. But he was unceremoniously outmanoeuvred by a factional pact involving two comrades and colleagues, Button and Brian Howe, which delivered Batman to the former and a Senate place to the latter. Mathews reflected ruefully on his humiliation. He was a consumed man – a restrained but recurring thread to Iola’s narrative of his life is that his restless ambition and incessant busyness exacted a toll on his family. Yet that drive was not matched by an aptitude for the calculated and hard clawing of political advancement. Mathews was candid about being, to some degree, a naïf in his chosen vocation: ‘Ideas and policies have always interested me more than the other aspects of politics. I’m not a natural politician in the conventional sense; I’m a displaced academic or something.’

A seat in the Victoria parliament was his consolation prize. Following a stint as principal private secretary to Holding and Wilkes, when he was once again immersed in coordinating policy development, he was tapped on the shoulder by the right factional powerbroker Robert Ray to stand for Oakleigh. He won the heavily Greek-populated electorate at the 1979 state election. The timing was propitious: Victorian Labor was in a rare sweet spot. A root and branch overhaul following federal intervention in the party at the beginning of the decade had paved the way for a surge of policy generation and an influx of talented MPs. The crowning of the readying of the party to end its generation-long exile from office was Cain’s elevation to the leadership in 1981. Mathews’s friend and fellow party reforming spirit, Cain was a man of impeccable integrity and serious moral purpose.

Elected in April 1982, Cain’s was a consequential, modernising social democratic administration. Though ultimately overwhelmed by financial and factional woes, it rewrote the order of Victorian state politics, ushering in an era of sustained Labor dominance at Spring Street. Mathews was an integral part of the government in its first two terms as minister for police and emergency services and the arts. In the former portfolio, he developed a remarkably respectful working relationship with the police commissioner, Mick Miller, a man he called ‘a prince of coppers’. Miller later asked Mathews to deliver his eulogy. Among Mathews’s achievements in the portfolio was disbanding the Special Branch, long regarded as a clandestine instrument for conservative harassment and intimidation of left political opponents. It was in the arts portfolio, however, that Mathews especially revelled. He presided over openings of different stages of the Arts Centre and inaugurated the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards, the Melbourne Writers Festival, and the Spoleto Melbourne Festival. His enthusiasm for arts events was ‘inexhaustible’; prolifically and beneficently he attended performances like a latter-day Medici. His briefer period as minister for community services was less congenial and produced little legacy, with problems such as child protection seemingly intractable.

Despite enjoying continuing support from Cain after Labor’s election to a third term in 1988, Mathews lost the favour of right faction powerbrokers to stay in Cabinet. Disappointed, he found solace in research and writing. Even while still a minister, he had become intrigued by cooperativism, his interest piqued by learning about the extensive system of workers cooperatives in Mondragon in the Basque region of Spain. It was a Eureka moment: ‘I was astonished. This was the “society of equals” I’d been looking for all my life.’ His discovery of cooperativism would lead him to the theory of distributivism and Catholic social teachings, absorbing the writings of G.K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc.

The fruits of this preoccupation over the following decades were two doctorates, two books, and countless talks proselytising the promise of cooperativism. Reading about this turn in Mathews’s thought, I couldn’t help but notice a parallel with Cairns: two reserved men who lived mostly in their minds, intellectual seekers who, having experienced the limitations and frustrations of political gradualism, detoured towards utopianism. Although Iola treats this development respectfully, she conscientiously notes the derision it provoked among some of her husband’s colleagues. Mathews admitted that Whitlam, a man whose conviction in the supremacy of parliamentary reformism remained immutable, perhaps ossified, despite the shock of the 1975 dismissal, regarded his colleague’s embrace of cooperativism as ‘a deplorable idiosyncrasy and departure from reality’.

The biography ends with Mathews’s public life gone full circle. By the early 2000s, he, along with other veterans of the 1960s Victorian Labor reform struggle, Cain and Button, deplored the party’s degeneration. The spring of the latter twentieth century decades had turned to winter: the party was virtually moribund at branch level, was rigidly controlled by factional oligarchies, a platform for narrow-minded careerists, and grassroots members were excluded from meaningful influence over its affairs. In 2009, Mathews warned: ‘We have become a shrinking, ageing and increasingly uninvolved party.’ To wage a renewed reform campaign, once more Mathews assumed leadership positions at branch and higher levels, created ginger groups, wrote letters, mentored the young, and organised conferences. Yet there is an elegiac quality to this stage of the book. Old comrades were dying; most painful was the loss of Whitlam and Cain. His own health was failing, and the party seemed even more impervious to change than it had in the 1960s.

In the twilight of his life, Mathews’s story still manages to uplift. He remains forbearing towards his beloved Labor Party: ‘[it] will often disappoint you, but it’s the only one we’ve got’. Despite memory and eyesight loss, he continues to tend to the life of the mind: listening to audiobooks, poetry, and music. If there is a lesson for Labor in this moving biography of one of the party’s finer modern sons, surely it is that its lifeblood depends on the bearers of ideas.

Comments powered by CComment