- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Einsamkeit und Freiheit

- Article Subtitle: A fine biography of an intellectual pioneer

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Aby Warburg (1866-1929) was an influential figure in the academic development of interdisciplinary studies during the early years of the twentieth century, and Hans Hönes’s excellent new biography charts the contributions and contradictions of Warburg’s life and work. Born into an immensely rich banking family in Germany, Warburg nevertheless resisted the expectations associated with his Jewish family background and, despite his grandmother’s hope that he might become a rabbi, opted to carve out for himself a career in humanities scholarship.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Giles reviews ‘Tangled Paths: A life of Aby Warburg’ by Hans C. Hönes

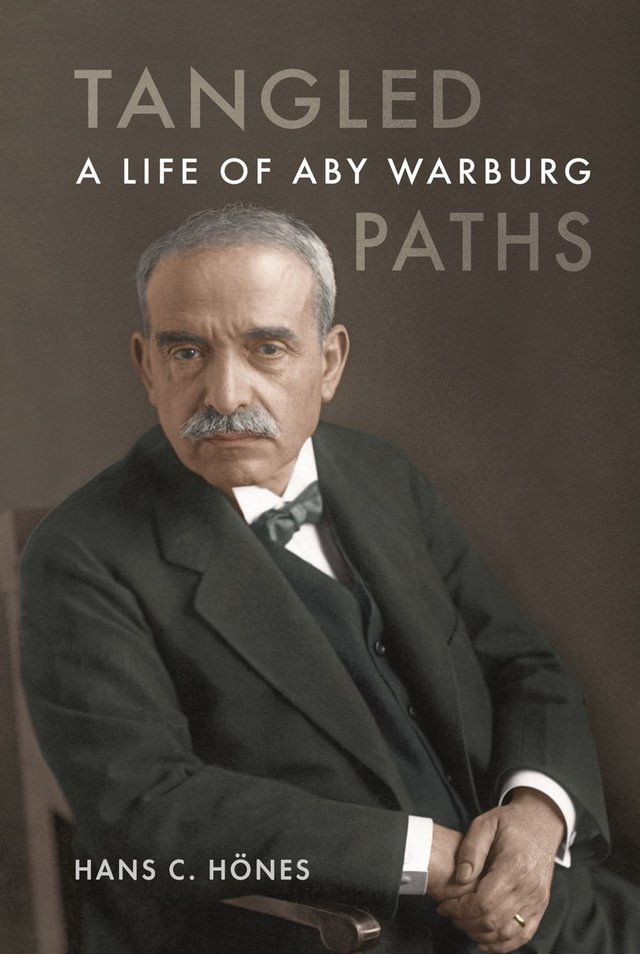

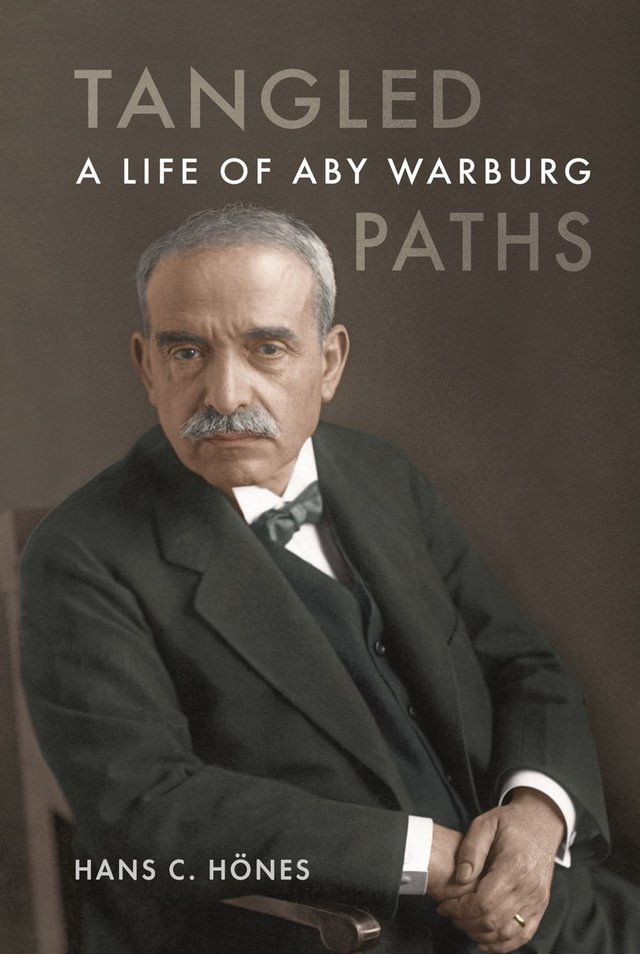

- Book 1 Title: Tangled Paths

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life of Aby Warburg

- Book 1 Biblio: Reaktion Books, $49.99 hb, 288 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Influenced by the nineteenth-century Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, Warburg developed an approach to art history that positioned famous paintings firmly within their historical context. Abhorring the Pre-Raphaelites’ tendency to idealise medieval iconography according to their own vague notions of spirituality, Warburg sought instead to relate famous artists like Sandro Botticelli to material factors that had implicitly shaped the artist’s work, such as various practices of drapery, astrology, or patronage. This disregard for received assumptions of inherent artistic value brought Warburg into conflict with some of the celebrated aesthetes of his day, such as Bernard Berenson in Florence, but it was to become a more standard approach later in the twentieth century, when many scholars became interested in intersections between high art and low culture. In this sense, Warburg might be regarded as an intellectual pioneer, though he had great difficulty in actually completing his own scholarly works. While he published various shorter essays, the ‘big book’ he had long planned failed in the end to materialise.

As Hönes observes, where Warburg was most effective was as a ‘research manager (as we might call it today)’. His family wealth enabled him to accumulate a vast personal library, which was linked up with the German national interlibrary loan system as early as 1905. He subsequently purchased a vacant plot next to his own house in Hamburg, where he established an enlarged, purpose-built library in 1926. This became integrated with the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg (KBW, or Warburg Library of Cultural Studies), the research institute that Warburg founded and directed until his death in 1929.

Disdaining the ‘big science’ that received an official imprimatur in Prussian universities around the turn of the twentieth century, driven by professors who were effectively civil servants implementing government agendas, Warburg sought instead to provide time and space for what he called the ‘monomaniac’ proclivities that he associated with a genuine search for knowledge. Wilhelm von Humboldt’s scholarly ideal of Einsamkeit und Freiheit (Loneliness and Freedom) served as a model and inspiration for Warburg.

Warburg once described himself as an ‘intellectual private banker’, and it is not difficult in retrospect to see the ironies and conceptual limitations bound up with his projects. Despite his interest in popular culture, he was personally dismissive of ‘the masses’, as well as often patriarchal in his dealings with women and paranoid in his relations with colleagues. On the other hand, he could also exude wit and charm, as Hönes notes, with a natural confidence deriving from his ‘societal standing’ as well as his family’s close connections with German high society. The celebrated art historian Erwin Panofsky was one of the first to benefit from Warburg’s mentorship, and the philosopher Ernest Cassirer also spent productive time at the Institute in Hamburg.

In 1933, this Warburg Institute was transferred to London, under the directorship of Fritz Saxl. The Nazi rise had made their ‘torch of German-Jewish intellectuality’, as Warburg and Saxl described it, impossible to sustain in Hamburg. During the next two decades, the Institute hosted many exiled Jewish scholars in London and became, in Hönes’s words, ‘a hub and intellectual powerhouse that shaped the British humanities, and Early Modern Studies in particular’. The Australian art critic Bernard Smith studied there in the late 1940s. Perhaps one of the few drawbacks of Hönes’s book is that he does not devote much space to the larger question of Warburg’s scholarly legacy. Although he remarks in the Acknowledgments that this book evolved from his time as a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute researching ‘Warburg’s Legacy and the Future of Iconology’, the focus of this particular work is squarely on Warburg himself. It might have been interesting to learn a bit more about the broad-er implications of Warburg’s impact on intellectual history in the longer term.

Nevertheless, what this book does it does exceptionally well. It is meticulously researched, with Hönes’s own position as a lecturer in art history at the University of Aberdeen enabling him to describe Warburg’s professional tussles with ease and expertise, though the author carefully avoids too many excursions into academic theory that might have been off-putting for the general reader. It is also beautifully produced by Reaktion, a publisher that specialises in art books, with many illustrations here reproducing excerpts from Warburg’s notebooks and his working drafts, along with the various forms of iconography that interested him.

Warburg’s parents deliberately named their first-born son ‘Aby’ rather than the more conventional ‘Abraham’, as if to give him licence to forge his own path away from the family heritage. He made the most of his good fortune and independent means to challenge the more rigid ossifications that had become prevalent in the German higher education system of his day. Calling himself at the end of his life ‘a historian of images’, Warburg was not himself a great scholar, but he did help pave the way for more influential scholarship.

Comments powered by CComment