- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The web of care

- Article Subtitle: A profound recognition of interconnectedness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As I began reading Elfie Shiosaki’s Refugia, shocking reports were emerging from the Western Australian coronial inquest into the death of sixteen-year-old Cleveland Dodd in Unit 18, the youth wing of Casuarina Prison, a maximum security adult prison. Before I had finished the book, the news came through of the death of another Indigenous teenager in custody. Decades after the devastating report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, with its clear and urgent recommendations, little has been done to keep First Nations people out of custody and safe when in custody.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Andy Jackson reviews ‘Refugia’ by Elfie Shiosaki

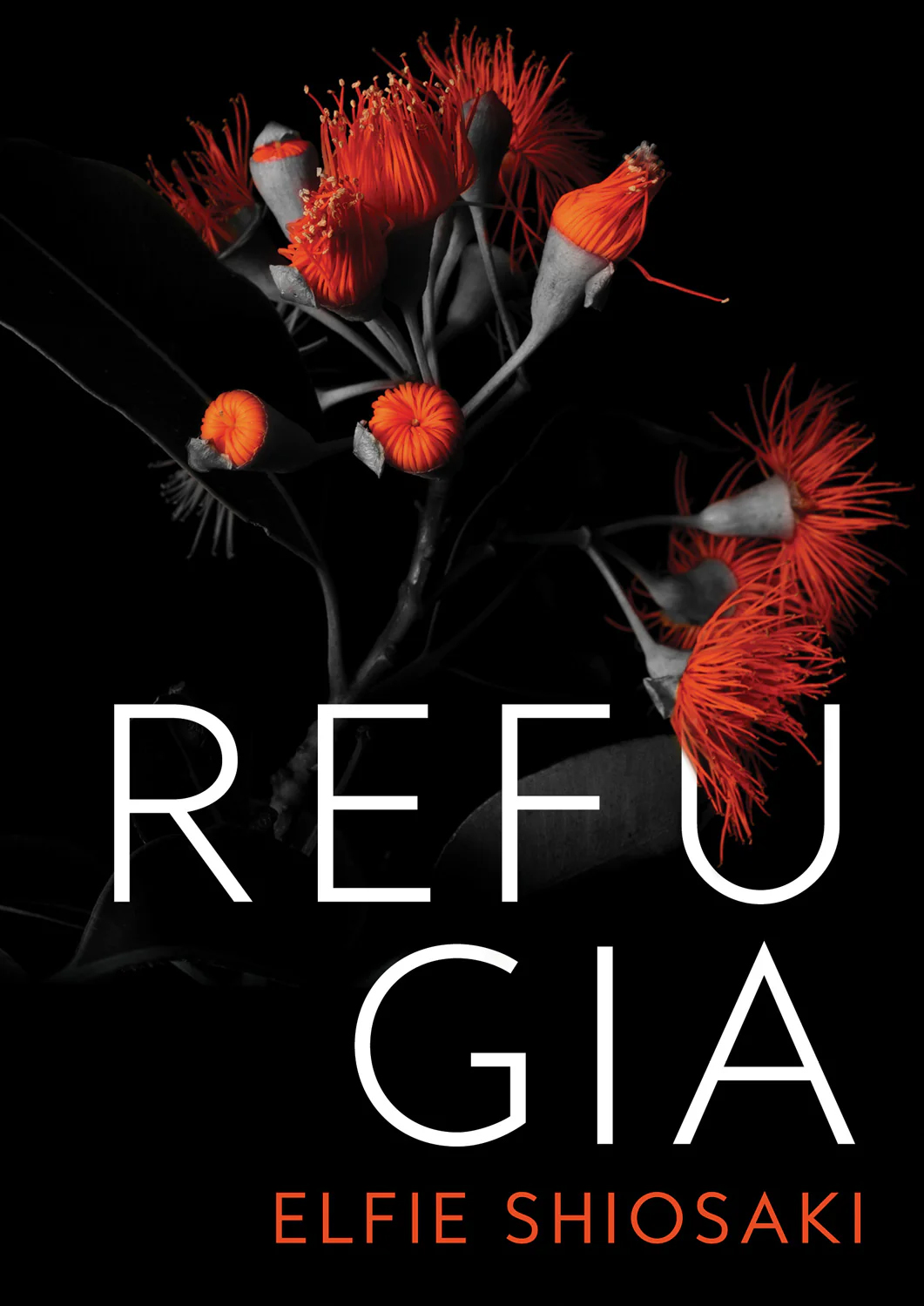

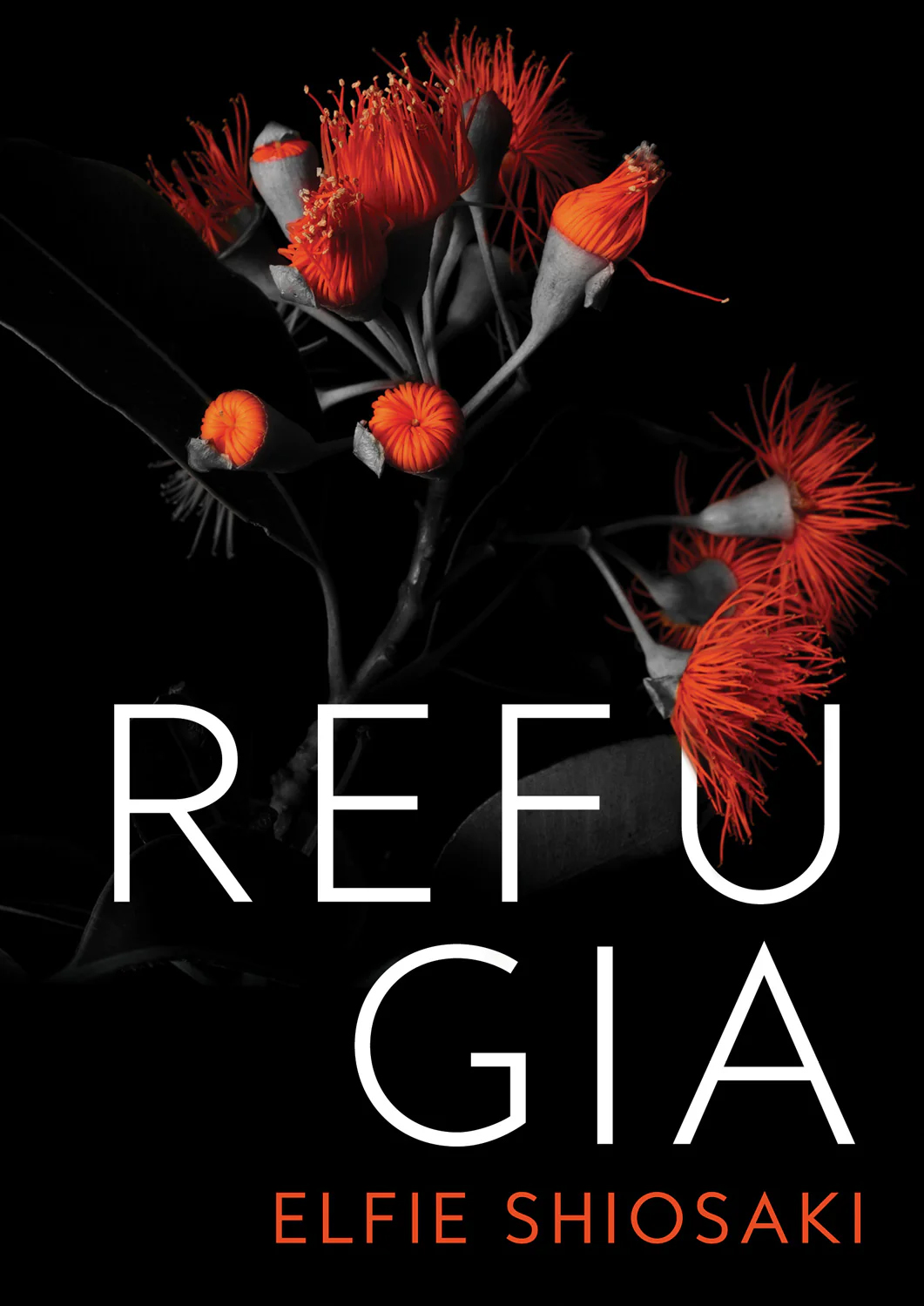

- Book 1 Title: Refugia

- Book 1 Biblio: Magabala Books, $27.99 pb, 89 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Shiosaki expands our understanding of how we got into this situation, through language that is both allusively lyrical and razor-sharp in its directness. In the poem ‘Wadjemup’, the island colonially renamed Rottnest, used as a prison and forced labour camp until 1931, is ‘paradise rebuilt as misery in 1838’, becoming ‘a holiday / from the stamina of holding ourselves / the way land holds history // and treads blood memory’. The poem that follows, ‘Monsters’, reads in its entirety, ‘Wadjemup prison / an embryo / for a monster / reborn as / Banksia Hill Detention Centre’.

Reading these poems feels like being cornered by a history that can no longer be denied. It is deeply troubling, yet therein also lies a kind of liberation. It reminded me of discovering Palestinian-American Noor Hindi’s poem ‘Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People are Dying’. Shiosaki, as Hindi does, defies the Western literary mainstream in both the thematic and stylistic concerns of her work, in order to bring the reality of what is happening – and what alternatives there may be – into the body of the reader.

Refugia, at its heart, is an interrogation of the history of Swan River Colony (now Perth), and a celebration of the vigour and endurance of the Noongar people and their Country. It does this from multiple angles and through an array of forms: documentary poetry and speculative verse; lyric and monostitch; found poem and image.

The book begins, fittingly, not with the creation of the colony, but the cosmic wellspring of Country. ‘A Galaxy of Stories’ depicts ‘a stellar nursery’ and ‘a blazing birthplace / for remembering, for forgetting’, so that history is revealed as a galaxy ‘stretching light from the early universe // hurtling towards my eyes’. The poetry that follows, then, seems to come not just from the poet but towards and through her, in a profound and subtle recognition of interconnectedness.

Numerous documents from the archive, both seminal and obscure, are reproduced and interrogated, unsettling their presumed authority: the Western Australian Act; newspaper reports from the early years of the colony; the writing of self-taught anthropologist Daisy Bates; and a photograph of the blasting of Fremantle Harbour. Refugia continues the tradition of fierce, rigorous truth-telling of books such as Natalie Harkin’s Archival Poetics (2019), Alison Whittaker’s Blakwork (2018), Charmaine Papertalk-Green’s Nganajungu Yagu (2019), and Shiosaki’s previous collection, Homecoming (2021). Collectively, they expose the blinkered, violent nature of the official archive, which hides as much as it records.

In ‘The Accuracy of This Report may be Implicitly Relied Upon’, Shiosaki quotes an 1834 newspaper report, employing strike-through against phrases such as ‘decisive encounter’, ‘system of lenience and forbearance’, and ‘atrocities committed by the tribe’, replacing them with, respectively, ‘massacre’, ‘systemic violence’, and ‘self-defence’.

The poem ‘Listen’ is addressed to Governor James Stirling, ‘founder governor of Western Australia’, asking ‘could you not hear the stars, / singing out to you?’. These stars would have ushered the British to meet with the Noongar on their terms, exchange stories, ‘to be cared for by Noongar boodja / until you returned home to your own country / with your belly full / and peace in your heart’. It is a familiar thought experiment but a devastating encapsulation of how Indigenous hospitality and sovereignty have been rejected.

One of the book’s most audacious and exhilarating poems is the titular ‘Refugia’. In a variation on speculative fiction, in 2029 a previously unidentified species of eucalypt, dormant beneath Perth for two centuries, breaks through the colonial surface to bloom into vigorous proliferation, so much so that the city itself is, ironically, declared ‘a prohibited area’, which becomes ‘a sprawling womb / for new plant and animal life’, where ‘the bodies of fresh and salt waters were tenderly // reunited // in an historic reckoning’.

The book’s ecopoetic approach is notable not only in how it articulates the environmental impacts of an extractivist, colonial mindset, but in its expansive use of first-person pronouns, revealing that the self, animals, Country, and the stars are interrelated in a web of care. ‘Everlasting’ gives voice to ‘wildflowers / buried in the shallow loam’, but it also feels like an extended metaphor for Indigenous resistance. ‘Sirius’ seems to oscillate or float in its perspective from astronomical to aquatic to human, never containable within any particularity.

As with Shiosaki’s previous collection, Refugia is arranged in three sections. Here, ‘bend’, ‘break’, and ‘bud’ collectively signal that while injustice can be devastating, it is not the last word. There is ample space in these poems for grief and exhaustion, as well as defiance and forgiveness.

In biological terms, a refugium is a remnant habitat in which organisms survive despite a surrounding catastrophe. This book is itself an environment of refuge and biodiversity, an embodiment of the renewal it anticipates.

Comments powered by CComment