- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

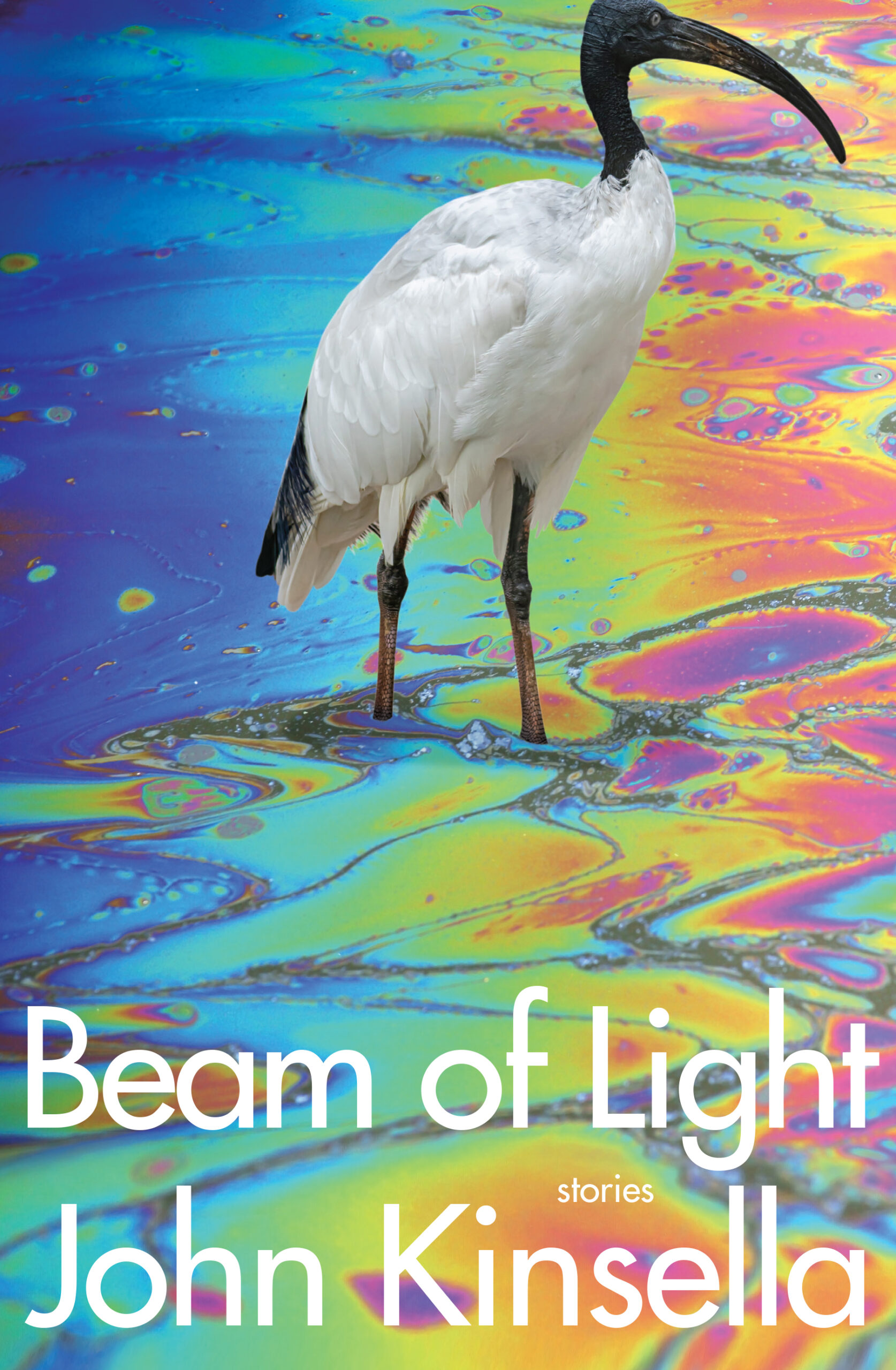

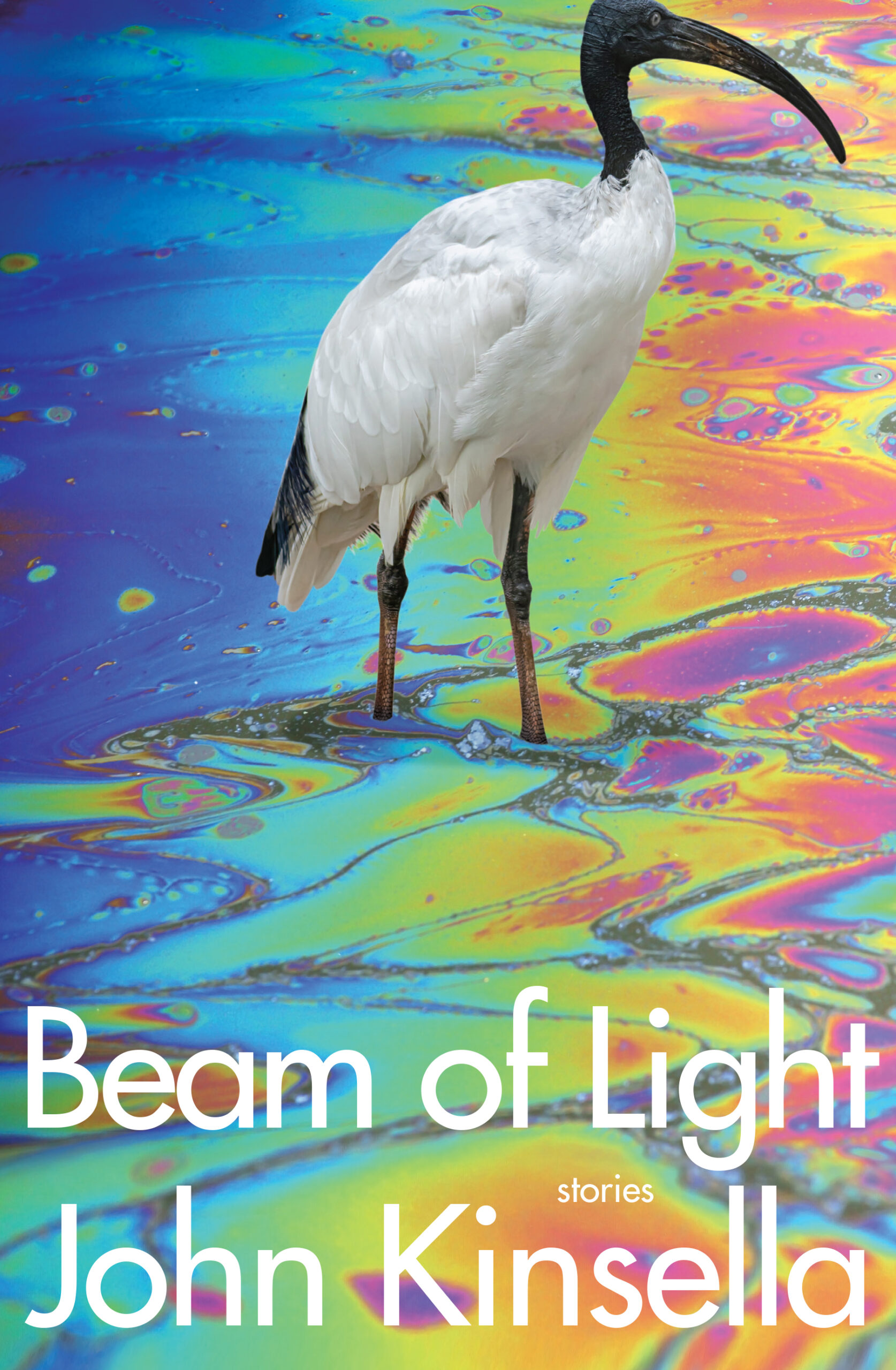

- Article Title: Misfits of the wheatbelt

- Article Subtitle: John Kinsella as an impressionist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

John Kinsella may well be Australia’s most prolific author – of poetry, fiction, short fiction, non-fiction. His extensive body of work is renowned for its obsessive concern, its fixation even, with a single place: the Western Australian wheatbelt, where Kinsella has spent most of his life. While psychoanalysis has fallen out of favour, Kinsella’s regionalism has the character of a repetition compulsion, a syndrome Freud related to unresolved trauma. In fact, what often underlies Kinsella’s repeated envisioning of the wheatbelt is the unresolved trauma of colonialism, as the land and all who rely on it – people but also animals and plants – suffer from the impacts of modernity. In this new short-story collection, Beam of Light, colonial ecocide provides the background for almost every story. At the foreground is a misfit, a figure certainly not unrelated to the colonial condition.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Maria Takolander reviews ‘Beam of Light: Stories’ by John Kinsella

- Book 1 Title: Beam of Light

- Book 1 Subtitle: Stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $32.99 pb, 261 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The misfit in this collection takes varied forms: paranoiac, conspiracy theorist, migrant, bohemian, Christian, arts student, environmentalist, redneck. In a colonised land – and when one lives on the land in such a way that the human presence is more visible – there are infinite ways of finding oneself out of place. This makes it difficult for anyone to gain the moral high ground, as the frequent coming together of opposite characters in these stories suggests – be it sensitive environmentalist and redneck, or arts student and stockbroker – for the misfit is always part of the same club. This is also something recognised in Kenneth Cook’s Wake in Fright (1961).

Kinsella’s story ‘The Winged Nike of Samothrace’ perhaps most clearly explores this relationship between settler colonialism and the condition of being an outcast. Despite its reference to classical myth, the story is resolutely quotidian, as are all the stories in this book. The outsider, after all, is the everyman. This story introduces us to a dental assistant named Becky who dreams of learning another language and travelling the world. ‘I don’t have a heritage,’ she asserts. Becky wants to find a language and a place in which she belongs, but she herself intuits that the way she is addressing the problem is ‘all wrong and I don’t know why’. Notably, the title of the story refers to a tattoo that Becky procures, which is also the name of a famous headless statue in the Louvre. That statue was stolen from Greece.

In a number of stories, the misfit is an addict. The eponymous story, ‘Beam of Light’, begins:

Under the overhangs of The Hills’ forests and blue metal quarries, where the couple had moved with their baby to start over, the red-brick house with its Spanish arches held them uneasy, restless. He was being treated for his addictions, though that wasn’t going so well, and she was taking an interest in continuing her education – if not going back to school, which she couldn’t stand, finding another way towards something other than what she had.

In this landscape rendered uncanny by modernity, defined by steel clotheslines and mines, what hope does this family have of being at home? The recovering addict is haunted by a guilty conscience. Memories of blackouts from his past were ‘a terror for him due to his not knowing, having no idea where he’d been, who he’d been, what he’d done’. His haunting calls to mind the Australian gothic, something evident in the iconic Picnic at Hanging Rock (1967), in which the gothic is typically read as a metonymic irruption of the repressed traumas of Australia’s past. Kinsella’s story doesn’t offer the same level of stylisation and allegorical resonance; the gothic and the figurative are barely present. Indeed, the man’s partner reassures him: ‘His blackouts were emptiness and loss, a collapse of body and soul.’ It is a strange form of reassurance, evoking an existential void as well as a moral one.

Children also figure prominently in this collection. The adolescent is, of course, an archetype of alienation. This is obvious in a story such as ‘The Wrangler’, in which the protagonist is a male teenager who takes up graffitiing his environment. While he sees himself as an aspiring Banksy, a girl in his art class, who is educated about the ecological impacts of spray paints, tells him that he and his mates are less rebels than ‘eco-reactionaries’. When it comes to younger children, their innocence is what makes them misfits. In ‘Playing Chicken’, a young boy is bullied into playing a game that involves dodging moving cars. The boy’s innocence provides the author with a tool of defamiliarisation, allowing Kinsella to interrogate normative values, such as those intrinsic to anthropocentrism. The child, for instance, questions the slur ‘chicken-hearted’. He reflects: ‘Chicken hearts are very small but keep a chicken going … chicken hearts are mighty things.’

The focus on chickens is typical of this collection, in which even animals are represented through outcast species. ‘Fox Skeleton’ sees a friendless teenage girl disassemble and disperse the skeleton of a fox ‘in spots she imagined it had roamed’. In ‘Burying the Rabbits’, a man of advanced years – another kind of outcast – buries rabbits that have died painful deaths owing to the myxomatosis virus. He inters rather than burns them to honour the fact that rabbits are ‘creatures who want to spend time under the earth, who are born under the earth’.

The stories in this collection aren’t ambitious with regards to form or polish, but Kinsella’s practice – as his prolific output suggests – is characteristically fast and light. One might think of him as a sort of impressionist. Whereas impressionists of old might have obsessed over European haystacks or water lilies, Kinsella gives us wheatbelt Western Australians in all their out-of-placeness, but without ever forgetting the quiddity they share with every living being.

Comments powered by CComment