- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Madeleine moments

- Article Subtitle: Brian Nelson’s new translation of Proust

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For German literary critic Walter Benjamin, translation belongs to the ‘afterlife’ of a work, by which he means the ‘transformation and a renewal of something living’. In this sense, a new translation extends this afterlife, renews and sustains it. This does not mean every new translation is worthy of the original, but it does bring it back into the light.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Felicity Chaplin reviews ‘The Swann Way’ by Marcel Proust

- Book 1 Title: The Swann Way

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, £9.99 pb, 477 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Proust is a very different kind of beast, however, not only because of the particularity of his prose (the famous ‘Proustian sentence’) but also because of the presence of C.K. Scott Moncrieff, through whom many English readers first came to know Proust’s novel. Nelson begins his translator’s note by acknowledging the looming figure of Moncrieff, which every new translation of Proust is produced in the shadow of. It is far from definitive, produced as it was under conditions far from ideal for translation, including an original manuscript full of errors. La Recherche was also incomplete at the time Moncrieff began, which made a holistic sense of the work impossible. Moncrieff’s translation was revised twice and somewhat improved by Terence Kilmartin and D.J. Enright respectively, but problems remained, such as the way he adapted the work for a more English, romantic sensibility, more his own than Proust’s.

As Nelson points out, Moncrieff’s language is dated and tends to make Proust ‘flowery’ when in fact his prose is ‘precise, rigorous, exact’. Nelson’s aim is to reproduce the precision and rigorousness of Proust’s prose, an approach he shares with Lydia Davis, who translated Volume One for Penguin. For Nelson, like Davis, translation is ‘a quest to find and reproduce a text’s voice’. Where he parts ways with Davis, however, is on the subject of fidelity, which can come at the cost of readability, particularly where the rendering of French into its idiomatic English equivalent is concerned. Davis’s fidelity or literalism sometimes produces rather obtuse passages in English. Nelson avoids this obtuseness through creative changes in the syntax to convey a clearer sense of the meaning. Nelson’s translation also differs significantly from the 1982 version by James Grieve. According to Nelson, Grieve, who describes himself as a ‘creative fidelicist’, offers a reworking rather than a translation, departing more radically even than Moncrieff from Proust’s original in order to better domesticate the French. An example of these different approaches can be found in the translation of Proust’s famous description of the experience of tasting the madeleine (‘un plaisir délicieux’), rendered as ‘an exquisite pleasure’ (Moncrieff), ‘a sweet feeling of joy’ (Grieve), ‘a delicious pleasure’ (Davis), and ‘a delicious feeling of pleasure’ (Nelson). Rather than assume a pugnacious attitude towards previous translations, Nelson practises what he calls ‘critical translation’, engaging as much with these previous translations as he does with the original. If something works, to his mind, it is retained, and it is discarded or reworked when it doesn’t. For example, ‘une partie profonde de ma vie’, which has been rendered ‘a whole section of my inmost life’ (Moncrieff), ‘a whole submerged area of my life’ (Grieve), and ‘an entire profound part of my life’ (Davis), is reworked as ‘a whole submerged part of my life’ by Nelson, revealing his dialogical approach to translation.

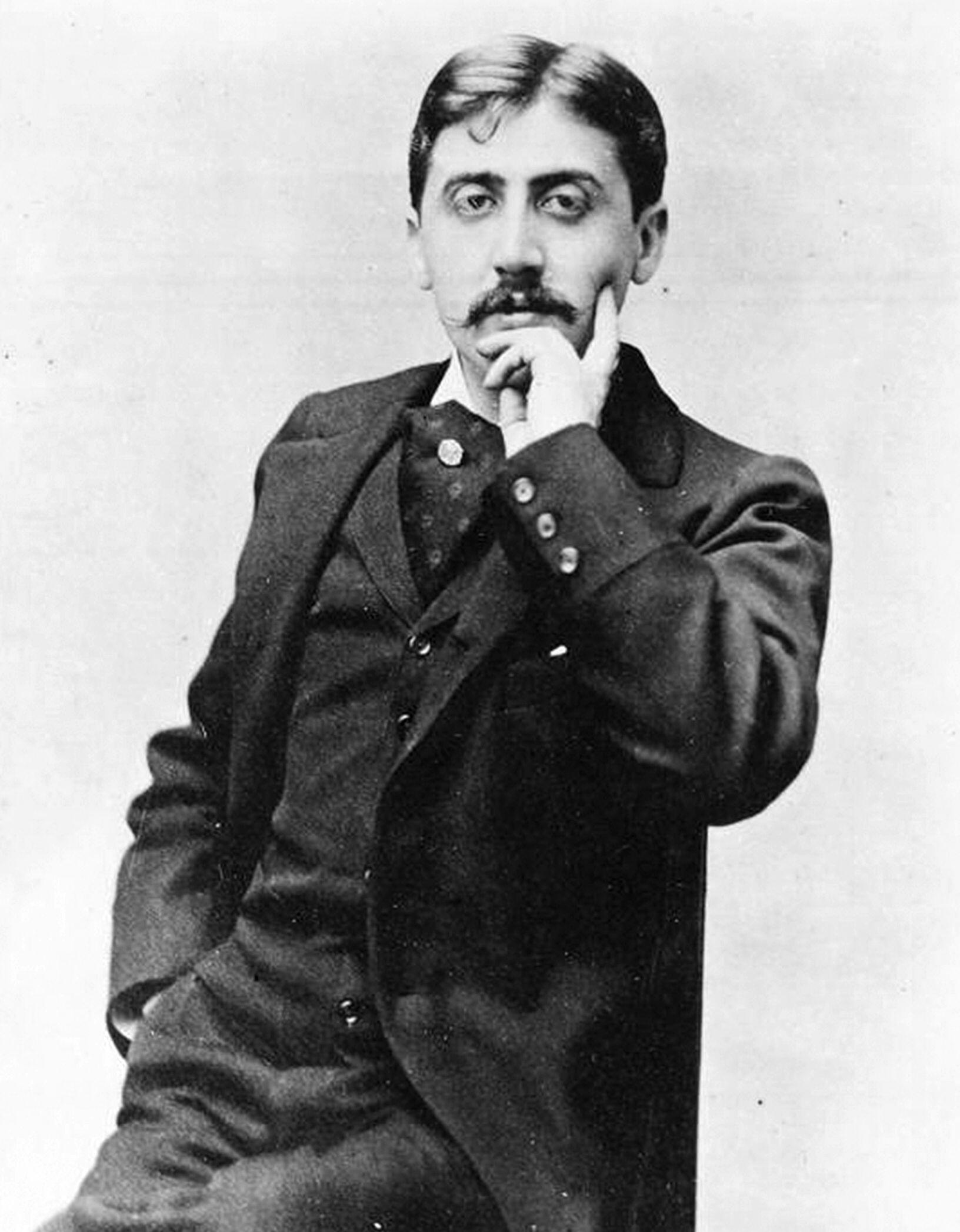

Marcel Proust (GL Archive/Alamy)

Marcel Proust (GL Archive/Alamy)

Nelson introduces two changes which may at first perturb readers more familiar with the Moncrieff translation. The first, and most obvious, is the title of the volume. For a long time, Moncrieff’s ‘Swann’s Way’ was the accepted rendering, so much so that any variation sounds jarring. However, Nelson argues that this wrongly places the emphasis on Swann himself, rather than on the path leading from the house in Combray to Swann’s house. Nelson’s choice of ‘The Swann Way’, he argues, complements ‘The Guermantes Way’ because it retains the ‘architectural’ structure of the book. Nonetheless, it takes some getting used to, and perhaps isn’t that much less awkward than Davis’s ‘The Way by Swann’s’ (a title imposed on her) than Nelson claims. ‘The Swann Way’ does, however, retain the play on the French côté (direction, way, custom) which Davis’s more literal rendering effaces. The second is the use of contractions, such as replacing the frequent I would with the occasional I’d. This creates an informal, conversational tone which he argues better captures the companionable nature of Proust’s narrator.

Translators of great works are often met with the question: why re-translate this? For Nelson, translations are first and foremost interpretations, and should be received with the same enthusiasm as a new interpretation of a famous symphony. What Nelson has achieved is not so much a new translation as a synthesis, the originality of his approach lying primarily in the way he has used his finely tuned ear to sound out what works and what doesn’t in previous translations, combined with a formidable understanding of the complex grammatical and syntactical structures of Proust’s prose.

Proust, himself a one-time translator, described translation as not ‘real’ writing but ‘drudgery in the service of others’. For Nelson, translation is both a creative and critical endeavour, almost on par with writing itself. This has the potential to reduce the drudgery but can also diminish the service, with sometimes mixed results. Striking the balance between creation and service should be the goal of translation, and this is something this new translation achieves

Comments powered by CComment