- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: History without vexed issues: Liquidating our memories of East Timor

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: History without vexed issues

- Article Subtitle: Liquidating our memories of East Timor

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Twenty-five years ago, an international peacekeeping force entered East Timor, delivered it from Indonesian occupation, and placed it under United Nations administration. Known as the International Force East Timor (InterFET), it had 11,000 troops from twenty-three countries and was commanded by an Australian major general. Everything about these events seemed miraculous. East Timor’s independence had long been regarded as impossible; a top adviser to President Franklin D. Roosevelt observed during World War II that it might eventually achieve self-government, but ‘it would certainly take a thousand years’. Indonesia invaded East Timor in 1975 while the latter was in the process of decolonising from Portugal, annexed it the following year, and declared its rule ‘irreversible’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

.png)

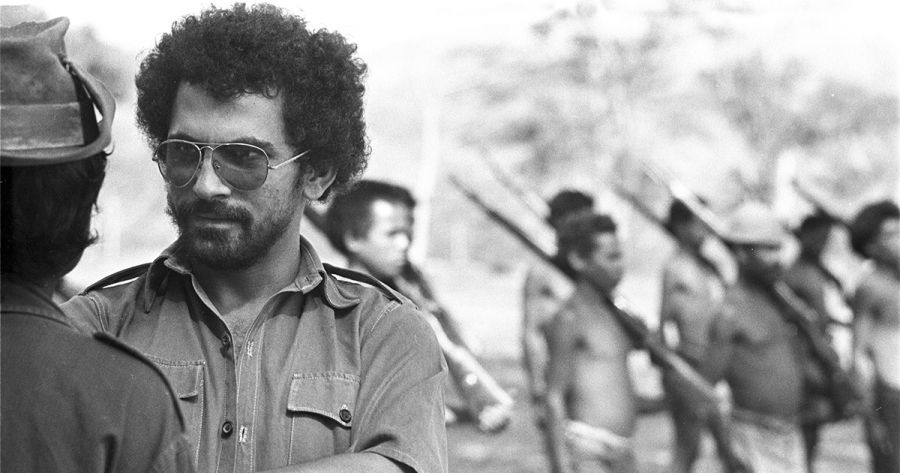

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jose Ramos-Horta with army recruits in East Timor, 1975 (Penny Tweedie/Alamy)

In 2004, the Howard government commissioned a six-volume Official History of Australian peacekeeping, humanitarian, and post-Cold War operations since 1947. East Timor, Afghanistan, and Iraq were not included, because military operations there were still occurring. However, a request to include East Timor was rejected even after operations concluded in 2006. The Labor government that followed under Kevin Rudd agreed to a new Official History series on Australian involvement in Afghanistan from 2001 and Iraq from 2003. Thus, there would be Official Histories covering operations from 1947 to 2006, in places as varied as Afghanistan, Cambodia, the Congo, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Haiti, Iran, Namibia, various Pacific nations, Rwanda, Somalia, Western Sahara, and Zimbabwe – but still not InterFET, which was the single largest Australian deployment since World War II, larger than the deployment to Vietnam at its height in 1967. It was one of the first times Australia had ever commanded a large multinational force. The informal veto had become too glaring to escape notice. Finally, in 2016, the Turnbull government agreed to include East Timor in the Official History series.

Professor Craig Stockings of the University of New South Wales was commissioned as the Official Historian. I first met Stockings when we were both in the Army. By coincidence, we later began working at the University of New South Wales. I had no involvement in the Official History nor any contact with Stockings once he moved to the Australian War Memorial in 2016. These observations are based on the published book and on government records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act by former Senator Rex Patrick and his Transparency Warrior initiative. Writing the history proved easier than getting it published. Stockings finished the manuscript in two years, but it took him another three years to have it cleared. All six Australian intelligence agencies cleared it, as did the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, the Defence Department, and the Australian Federal Police. The hold-out was the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), which objected that the manuscript ‘focuse[d] inordinately on historical matters’ and that it was ‘not only excessive but out of scope’. It argued against ‘reviewing often vexed issues over the preceding half-century’, and recommended that ‘the first nine chapters be compressed into one or two’.

DFAT’s hostility to an analysis of its record was understandable. Stockings shows in Part I (Strategic and Policy Context) that in 1969 Australia began issuing oil exploration permits for parts of the seabed that were much closer to the coast of Portuguese Timor than the coast of Australia. When the Carnation Revolution of 1974 put Timor’s decolonisation on the agenda, the then-Department of Foreign Affairs noted that there were ‘good possibilities’ for oil or natural gas under the waters, and that the Indonesian position on who should control them would be more acceptable to Australia than the Portuguese position. Stockings demonstrates that Australian diplomacy influenced Indonesia’s decision to invade East Timor in 1975. A few other historians had previously identified oil as a factor behind DFAT’s actions, but now Stockings says it with the benefit of access to security classified government records.

After the Indonesian invasion, Stockings writes, DFAT officials ‘would speak and act about Indonesia’s actions in East Timor so as to minimise the public impact at home’. A bipartisan consensus ‘provided successive governments with a margin of comfort necessary to neutralise public opinion’, especially since the ‘litany’ of accusations of Indonesian violence was ‘long and gut-wrenching’. Stockings describes a ‘business as usual’ mentality in Jakarta: Indonesia’s generals and policy planners learnt to ignore DFAT’s perfunctory statements doubting or deploring violence, secure in the knowledge that they could treat the Timorese as they wished. As Stockings observes, ‘how such consistency might have been viewed from Jakarta cannot be over-emphasised’.

These are not merely historical curiosities, and Stockings does not bring them up gratuitously; he shows, correctly, that they were pivotal to the dramatic events of 1999, as the Timorese prepared to vote on independence. While Indonesia trained, armed, and deployed militias in a campaign of terror against the population, Foreign Minister Alexander Downer disputed both the facts and their cause, saying that ‘if it’s happening at all, it certainly isn’t official Indonesian Government policy’. Rather, it may be the work of ‘some rogue elements within the armed forces’.

Two decades later, DFAT still wanted Stockings to refer to ‘militias’ in East Timor, not the Indonesian Army’s creation and command of them. It objected that ‘Annex 2’ was ‘out of scope and of particular sensitivity’. I suspect that Annex 2 is a detailed study of the order of battle of the Indonesian militia groups in East Timor, and their covert controllers in the Indonesian intelligence and special forces units. Stockings notes that in 1998 Australian solidarity activist Andrew McNaughtan smuggled out a rich trove of information about Indonesian troops in East Timor, including the militia groups, their structure and their salaries, via an East Timorese resistance spy who had infiltrated Indonesian headquarters in Dili. Annex 2 is not in the Official History. Rex Patrick has since filed a Freedom of Information request to obtain it.

Many official historians ignore the role of ordinary activists and other scruffy sans-culottes in war and anti-war movements – not this one. Stockings describes a quarter century of work by the international solidarity network for East Timor. Unlikely alliances took shape: old soldiers from World War II, trade unionists, peace activists, communists, social democrats, and conservatives. As Stockings says, ‘This foundation of support, constructed over an extended period when East Timor was widely regarded as a lost cause, helps explain the strength and resilience of international interest in the dramatic months of 1999.’

Stockings demonstrated commendable resolve in resisting DFAT’s pressures. In arguing for full publication of his history, he put his analytical talents to work, explaining how InterFET’s success relied on logistics, equipment, intelligence, military force, and the Australian Defence Force’s high standards of realistic training during the 1990s, when overseas deployments were few and far between. Australians have good reason to be proud of their military’s determination and professionalism in 1999. Junior leaders ‘carried responsibilities and bore attendant risks well above their rank and pay grades’. The mission was ‘one of the most successful United Nations enterprises of its type ever seen by any sensible measure’. InterFET accomplished its mission ‘at the lowest possible cost in human life and within only 157 days’.

Twenty-four years of international solidarity and a military intervention at the very end were important, but the East Timorese resistance, which operated in urban areas and in the countryside, played a major role in the final outcome. The resistance could never match the Indonesian military’s capacity for violence, and didn’t try to. It made a conscious decision not to target Indonesian civilians in East Timor or Indonesian diplomats overseas. There was a clear demarcation between the right of armed resistance against the Indonesian army and the strategic non-violence of the rest of the campaign. Such restraint made it much easier for mainstream Australian politicians and other establishment figures to openly champion the cause of East Timor. Strategic non-violence gave the cause a structure of legitimacy in the West.

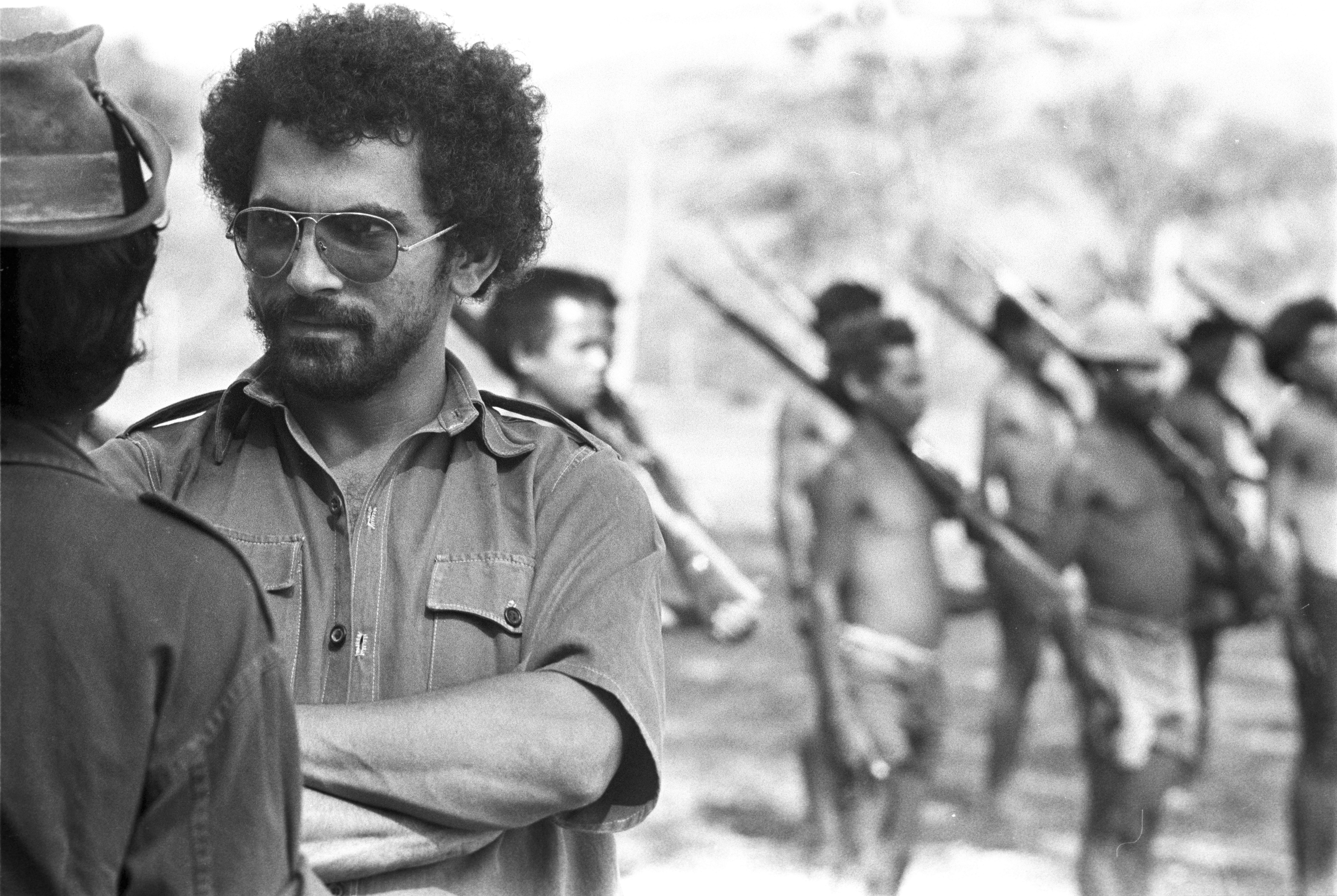

José Ramos-Horta with army recruits in East Timor, 1975 (Penny Tweedie/Alamy)

José Ramos-Horta with army recruits in East Timor, 1975 (Penny Tweedie/Alamy)

The resistance was outnumbered and outgunned, but it had confidence in its own people throughout twenty-four years of occupation. It strengthened Timorese society by preserving culture and identity. Despite the occupying force’s attempts to turn them into Indonesians, the East Timorese preserved a coherent sense of difference. With help from the Mary MacKillop Institute of East Timorese Studies in Sydney, Tetum language schoolbooks became the basis of the Tetum language program in schools in the Diocese of Dili in the 1990s. That program complemented the Tetum-language Catechism and liturgical texts used in the Mass and the Sacraments. The oath of the clandestine National Resistance of East Timorese Students was written not in Indonesian but in Portuguese, and never translated into any other language. New members would take the oath in a quasi-Christian ceremony, drinking red wine to signify Christ’s blood and praying for the Virgin Mary’s help. They developed connections with Indonesian Christians from Flores, Solor and elsewhere in eastern Indonesia, preserving a sense of being a beleaguered Christian minority in a Muslim-majority Indonesia.

An important signifier of East Timorese culture has long been the traditional hand-woven cloth known as Tais. Tais are woven mostly by women, on simple back-strap looms with a small selection of cherished tools such as honed mortars, pestles, and cloth battens. The methods and techniques are passed down through generations of women by oral tradition and applied practice. Tais play a key role in East Timor culture, notably in rituals of birth, traditional marriage, and death. Tais are considered so culturally important that they were added to UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding in 2021.

Historically important Tais are on display at the Tais, Culture, Resilience exhibition being held at Trinity College (Melbourne University) from late September until UN Human Rights Day on 10 December 2024. One pair was woven more than eighty years ago using cotton, plant-based pigments, ground shells, lime, and different kinds of mud. The work is called Tais Kaben (wedding Tais). It consists of a Tais Nunukala for the bride, Bui Mah, and a Tais Naeleki for the groom, Watu Lae. These are the couple’s indigenous Timorese names, not the Portuguese names given in a Catholic baptism. Indigenous marriage links the two people who marry, and also their entire kinship groups. The Tais come from a mountainous, forested region known as Iliomar in the south-east corner of East Timor. They are displayed courtesy of a former resistance fighter whose Catholic name is Balbina da Conceição. She has been highly decorated for her contribution to the East Timorese resistance. Ms da Conceição was a member of a three-woman courier and support cell, along with Hilda Madeira and Olympia da Costa. They provided vital logistical support to the armed resistance in the jungle.

The Australian military historian Brigadier (retired) Ernie Chamberlain has documented what the Indonesian army did when they captured twenty-one-year-old Olympia da Costa:

Olympia was tortured and raped. Afterwards, she was stripped to the waist and, wearing only a very short nylon shift, was paraded on foot through the six villages ... Two of her senior male relatives held her hands ... and at each village she was forced to warn villagers of the penalties for resistance and supporting [the resistance]. Later that evening, she escaped from [the barracks], but was recaptured at her parents’ home [where] she had tried to gather clothing before fleeing into the jungle … She was bayoneted in the throat and died.

The Indonesian forces targeted Olympia and other women like her because they were active resisters. Some women bore arms alongside men. Others provided logistical support, took on clandestine organising tasks, and had primary responsibility for the well-being of families. Their traditional knowledge of medicines and midwifery was invaluable to the guerrilla fighters and the internally displaced population in the mountains.

Another Tais loaned to the exhibition was woven more than fifty years ago by a weaver named Juana dos Reis, who was born in the 1940s. Her life changed drastically in 1977, when she joined tens of thousands of other East Timorese civilians trying to escape aerial bombardment by the Indonesian Air Force. The attacks included the use of napalm to destroy crops, livestock, and other food sources. The defenceless civilian population was detained in camps that lacked medical care, toilets, and shelter. Cholera, diarrhoea, and tuberculosis were rife. Stockings writes about ‘the enormous suffering inflicted on the civilian population’ and the mass deaths caused by ‘shortages of food, medicine and shelter’. To his credit, he cites the most accurate analysis of the death toll: ‘approximately 200,000 people, or almost a third of the population, died as a consequence of the resulting famine’, noting that this was ‘likely a conservative estimate’.

The overwhelming majority of deaths occurred during a nineteenth-month period in 1978 and 1979. An Australian intelligence study in 1976 concluded that Indonesia received ‘the greater part of her military aid from the US, and the remainder from Australia’. No wonder DFAT complained that Stockings’ book focused ‘inordinately on historical matters’ and reviewed ‘often vexed issues over the preceding half-century’. You can’t let ordinary Australians know what’s being done in their name. They wouldn’t tolerate it.

Juana dos Reis fled her village, taking this exquisite Tais, and walked the long and arduous journey to the foothills of Mount Matebian (the Mountain of Spirits). She survived her detention in one of the concentration camps. She sold her Tais in 2004 for a pittance because poverty was rife in post-occupation East Timor. It is now in the custody of East Timor Women Australia, a Melbourne-based group that has worked with East Timorese women for more than twenty years and has partnered with Melbourne University for the current exhibition.

The Official History by Craig Stockings and the exhibition by East Timor Women Australia and Melbourne University are forms of resistance to historical denial. They exemplify Milan Kundera’s observation that ‘[t]he first step in liquidating a people is to erase its memory… The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.’

This article is one of a series supported by Peter McMullin AM via the Good Business Foundation.

.png)

Comments powered by CComment