- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The pledge

- Article Subtitle: J.C. Watson and the art of the possible

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At various times in its history, the Australian Labor Party’s strict insistence that its parliamentarians vote along party lines or face expulsion has caused angst within the party. On the one hand, the practice means that talented party members might be lost to the ALP; on the other, party solidarity is the key to passing legislation and to maintaining cohesion. One of the early architects of Labor’s strict party discipline was J.C. Watson, who was a major figure within the labour movement between 1890 and 1916.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Lyndon Megarrity reviews 'In Search of John Christian Watson: Labor’s first prime minister' by Michael Easson

- Book 1 Title: In Search of John Christian Watson

- Book 1 Subtitle: Labor’s first prime minister

- Book 1 Biblio: Connor Court Publishing, $29.95 pb, 202 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

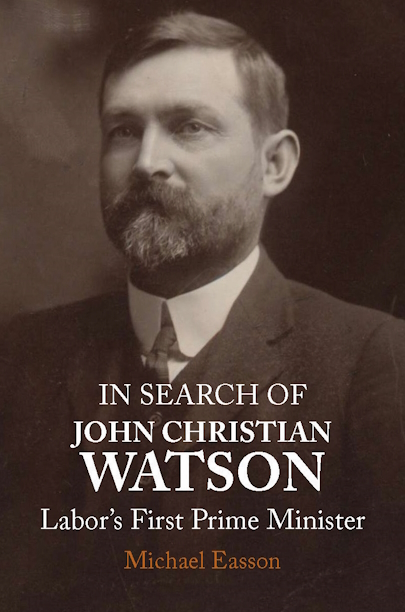

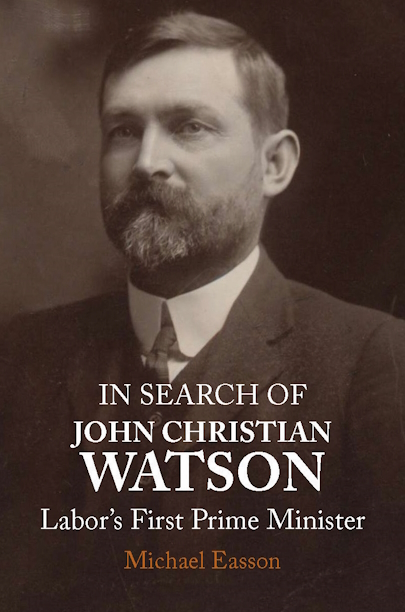

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

After leaving the federal parliament, he remained a tireless worker for the Labor cause until he was expelled in 1916 because of his pro-conscription stance. Fortunately for Watson, he was able to reinvent himself as a businessman, becoming a long-serving president of the National Roads and Motorists’ Association (NRMA) and a director of Australian Motorists Petrol Co. Ltd (Ampol).

In Search of John Christian Watson concentrates on Watson’s early years and his political career. A theme quickly emerges in the book of Watson as a practical Labor reformer: he did not so much ‘reach for the stars’ as grasp the art of the possible. To achieve the ALP’s material goals, such as industrial reform, electoral reform, and pensions, Watson stressed the importance of a uniform Labor vote in parliament (or ‘the pledge’) and cross-party support.

Michael Easson has a clear passion for Labor’s history and Watson’s role in its early years. A highlight of the book is the chapter on Watson and defence policy. Watson appears to have been influential in securing federal Labor support for compulsory military training, justifying it on the grounds that government interventions like old age pensions should be accompanied by a willingness of the young to defend Australia. Another effective section of the book is on the Labor split of 1916. The author explains fluently how devastating the World War I conscription issue was for the Labor Party, and by implication for expelled pro-conscriptionist Watson:

When the Labor tree shook free of pro-conscriptionists … it was not as if falling leaves gently wafted and circled to the ground. Whole limbs of the tree were … torn-off … Labor … comrades in so many political contests over time, were now ranged against each other.

The author also provides intriguing glimpses into Watson’s post-political life, especially his lobbying and leadership on behalf of the NRMA. Watson gave the impression that the NRMA was non-political, but in some respects it was highly political, given its emphasis on pressuring government to improve road infrastructure, support ‘worthy’ road projects, and reduce petrol taxes.

Despite its merits, the book shows numerous signs of being rushed to publication. The author has not, in my view, succeeded in presenting a cohesive and fresh portrait of the first Labor prime minister. There are structural problems; the book contains a mixture of sequential and thematic chapters that can be hard to follow. Furthermore, due to an over-emphasis on quoting secondary sources, sometimes at great length, Easson’s authorial stamp is often missing. At times, the words of Graham Freudenberg, Bede Nairn, Al Grassby, and other historians of the labour movement are recycled uncritically, without much attempt at uncovering new perspectives on Watson through parliamentary debates and other primary sources.

Elsewhere, the author’s discussion of various aspects of Labor history occasionally shifts the attention away from Watson as a biographical subject. This seems a pity, as there are many missed opportunities to gain a greater insight into Watson’s career and his personality. Watson’s relationship and influence on fellow élite Labor politicians, such as Andrew Fisher, could have been a greater focus of the book. Further, Watson’s prime ministership is too quickly passed over: for example, what were the six bills which his administration managed to pass, and what impact, if any, did they have? Finally, more could have been made of Watson’s neglect of his electorate during his last twelve months in Parliament, during which time he spent nine months managing a gold mine in South Africa. For a figure who is generally portrayed by Easson and others as a selfless servant of the Labor Party, this incident comes as a jarring surprise and surely warrants more investigation.

A short literature review would have been a useful addition to the book. Watson is the subject of a number of previous political studies, notably Ross McMullin’s So Monstrous a Travesty (2004). Detailed discussion of such texts would have helped the reader understand Easson’s approach and how it differed from competing publications.

There are a few typos which detract from the reading experience. In many cases, the illustrations lack contrast and are poorly reproduced. Some of the photos are clearer, although additional processing of these would have enhanced their presentation.

In Search of John Christian Watson provides a sound overview of the life and times of Australia’s third prime minister. However, a deeper dive into the archives, parliamentary sources, and newspaper collections would have created a fuller picture of this important Labor politician.

Comments powered by CComment