- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is the second major retrospective of the art of Eugene von Guérard (1811–1901). In 1980 he was seen as Nature-inspired, like the German Romantics and the Humboldtian visionaries Frederick Church and Thomas Moran (American painters of von Guérard’s own generation). This time, the viewpoint is science.

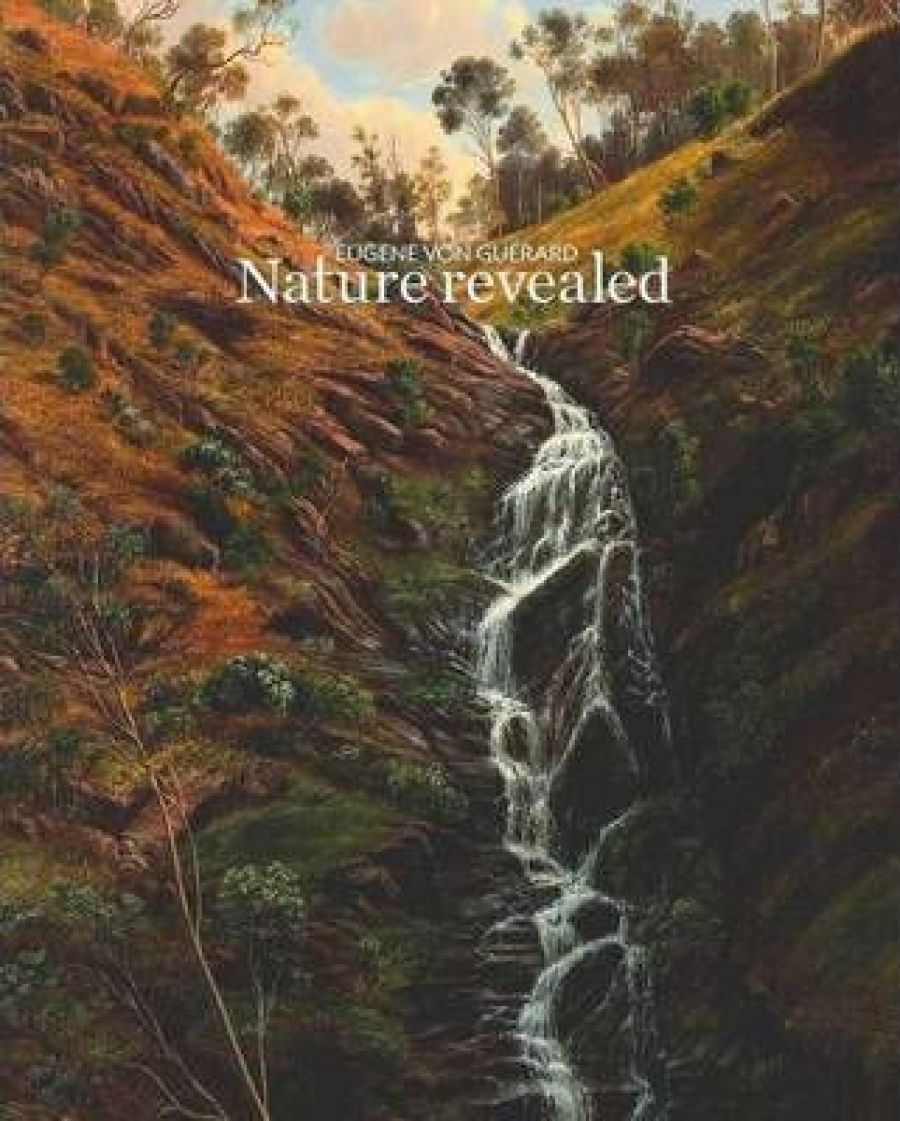

- Book 1 Title: Eugene von Guérard

- Book 1 Subtitle: Nature Revealed

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Victoria, $49.95, 302 pp

Twice in 1870, von Guérard had occasion to say that he tried to interpret nature intelligently. He wrote to a geologist friend that his lithographed Australian Landscapes ‘demonstrate the character of the Australian landscape faithfully and with truth to nature’. To James Smith’s stinging criticism that his ‘minutely laborious description ... would make delightful illustrations of a treatise on the botanical or geological features of the colony’, he responded that, if he succeeded there, he was confident his paintings would have greater value in the future. Those were prophetic words; the current exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria honours a great painter. On the other hand, I see no reason why Smith’s demeaning measure should be used to assess von Guérard, who aspired to a higher art than ‘laborious description’. Likewise, Alexander von Humboldt (the ghost at this feast of von Guérard) impressed himself upon history by memorable word pictures, not statistics.

Von Guérard’s sketchbooks had informed us about his travels in Italy with his artist father, and early oil paintings occasionally appeared in the market, but until this exhibition the social contexts in which he acquired style, subject, concept, and finish were little known. The fine detailing of Tor di Quinto (1830–31) was learned from Bernard von Guérard, whose pencil drawings of scenes in southern Italy are displayed side by side with Eugene’s corresponding sketchbook. Comparison reveals that Eugene departed from his father’s intimate approach in preferring panoramic scenes, a bolder touch, and a dramatic motif. The next section of the exhibition, the freshest and most exciting, has oil sketches and studies of rocks, earth, and plants painted by artists of Düsseldorf from the 1830s to the 1850s. Disarmingly unpretentious bits of nature – dubbed ‘cut-outs’, ‘parts’, and ‘foregrounds’ by the painters – they introduce us to the far-reaching consequences of painting ‘faithfully with truth to nature’.

During twelve years at Düsseldorf (1838–51), von Guérard learned to design from a scene’s physical form and ongoing life. The ‘parts’ of nature were unpretentiously composed by the Düsseldorf painters, yet composed they were. For instance, in von Guérard’s Grafenberg, painted in the open air on 12 August 1841, a spiral forming loosely in the wind-tossed foliage tightens towards a small round pool in the orange gravel. Looking for nature’s meaningful design became the rule for von Guérard, in whose major paintings the composition is a single body breathing its own life.

Inside the scene, there is magic in the way the details gradually unfold. Von Guérard exercised three distinctive techniques for the slow release of pictorial details: giving life to shadowed foregrounds by employing contrasting hues of subdued tone; extending the range of vision by telescoping distant objects; and articulating natural patterns and groupings. Like nineteenth-century scientists and poets, he focused on microcosm and macrocosm. The small, dark, sharp angles of a ‘Jacob’s ladder’ of narrow rocks, down which the Strath Creek tumbles for three quarters the length of one of his canvases, meaningfully repeat the V-shape of the sunlit gully at the top. In the skies of many a panoramic scene an eagle hovers, buoyed up by the invisible current of air rising from sunburnt plains. Science-minded colonists would appreciate that the painter made visible the cause and effect of heat, air, and convection current. Those two pictures correspond to science, yet von Guérard was equally committed to history. A closer look into a landscape strewn with giant volcanic boulders (Stony Rises [1857]) reveals a family living in the shadow of the rock, their bodies lightly gilded in the sunset of an Australian golden age.

The book-catalogue is a rich resource, superior to the excellent 1980 catalogue, and much less expensive than the 1982 book. It is also a welter. For the editors, the overlap, repetition, and disagreement between four narratives of von Guérard’s life must have been challenging; and the centripetal force created when thirty-seven writers give the points of view of their several disciplines in 101 essays about individual works, grouped thematically, makes for incoherence. In the circumstances, an index is mandatory, but there is no index. Too often the texts blur between fieldwork and what is less precisely identifiable in a painting; conflate present and past and what von Guérard could have known with what the writer knows; and lump together ideas and approaches that evolved and changed over half a century. Errors of commission and omission: Humboldt had nothing to do with Thomas Ender’s trip to South America or Johann Moritz Rugendas’s first trip. Humboldt, in the field, utilised modern instruments of measurement; von Guérard had only his eyes. The paucity and imprecision of von Guérard’s studies of flora and fauna prove he was not a scientific draughtsman. When he painted Tower Hill, much of the land around was being cleared – in part for Dawson’s fuel-hungry tallow factory – and within a year Tower Hill was bare. After reading the text, we are wiser about where to locate the artist in his period’s widespread search for meaning in the body of nature, but our understanding would be more balanced had the writer included farmers who occupy farmlands once painted by von Guérard, surveyors (such as Neumayer) and miners, explorers, ethnographers (such as Howitt), and newspaper critics. I suspect that science and ecology have the same intervening role in the book-catalogue as the interventions of contemporary works of art in the NGV’s nineteenth-century displays: they show the art in relation to the concerns of the present.

One could say of von Guérard that for all his scientific regard for nature he really aspired to a more honest sort of view painting. His paintings provide a scenic tour through Victoria (plus a few places in New South Wales, South Australia, and New Zealand). Some decades ago, naval commander Dacre Smyth visited many of von Guérard’s sites and, from von Guérard’s viewpoint, faithfully painted his own version. The scenes that Smyth painted had not changed much since von Guérard’s time. Fred Williams’s experience was different. Inspired by the magisterial Waterfall, Strath Creek (1862), he clambered down the falls but found the lower gully choked by undergrowth (he managed a handsome painting of the upper falls nonetheless).

The tenor of science, patronage, and art went wrong for von Guérard in Melbourne. From mid-century, around the world, the door was closing on public participation in scientific research. Moreover, modern specialisation made his holistic approach seem old-fashioned. His best patrons were farmers (who shared his skill in interpreting natural phenomena), but they did not have bottomless pockets or endless wall space. Metropolitan patrons took their cue from local art critics, who were ill-equipped to appreciate his art. Although critics still liked grand and imposing subjects – when the artists were Gully and Johnstone – the trend in painting was towards informality. Von Guérard understood that his intensity of observation offended some. His late paintings were grandly comprehensive, but harsher and less receptive to close examination than his previous work. It made no difference. In the eyes of Melbourne’s critics, von Guérard was always and only a ‘literalist’. The test that critics failed him on was ‘poetry’. Von Guérard owned many books of poetry, and possibly wrote some himself. Poetry may have meant more to him than to the critics who wielded the term like a baton and who, each year, were more categorical about what distinguished poetic painting from the merely literal. Landscapes became poetic when the painter ‘vivified’ them. A poetic impression would be ‘noted on canvas at the moment the scene vividly impressed itself upon the mind of the observer’. Von Guérard’s ‘regularity’ of wave and foliage was condemned by the Australasian (23 March 1872) for suggesting ‘reminiscence’ rather than a spontaneous transcript.

The critics were mistaken in thinking that he did not paint from nature. One of the ironies in the artist’s story, Michael Varcoe-Cocks tells me in conversation, is that on 18 January 1873, while von Guérard sat painting two oil studies on the headland at Cape Schanck, a ship carrying the commissioners who had selected works for the forthcoming London International Exhibition was lying-to in the mist a short distance away. The taste-makers could not see von Guérard’s lively response to nature, nor could he understand their rejection of his art.

Comments powered by CComment