- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Encompassing installation, sculpture, drawing, photography, and the moving image, Patricia Piccinini’s fifteen-year survey exhibition of sixty-five works at the Art Gallery of South Australia coincides with the period of her exploration of issues surrounding genetic modification/manipulation in the biotech era. Piccinini’s investigations are, as the exhibition’s title suggests, cautionary tales.

- Book 1 Title: Patricia Piccinini

- Book 1 Subtitle: Once Upon a Time ...

- Book 1 Biblio: Art Gallery of South Australia, $75 hb, 148 pp

Piccinini, who represented Australia at the 2003 Venice Biennale, has become known for her hyperrealist tableaux of humans (predominantly children) and transgenic creatures – composed from silicon, fibreglass, and real hair – that are alternately or simultaneously repellent, endearing, and even seductive. For American theorist Donna Haraway, Piccinini is a powerful storyteller who belongs to ‘a radical experimental lineage of feminist science fiction’.

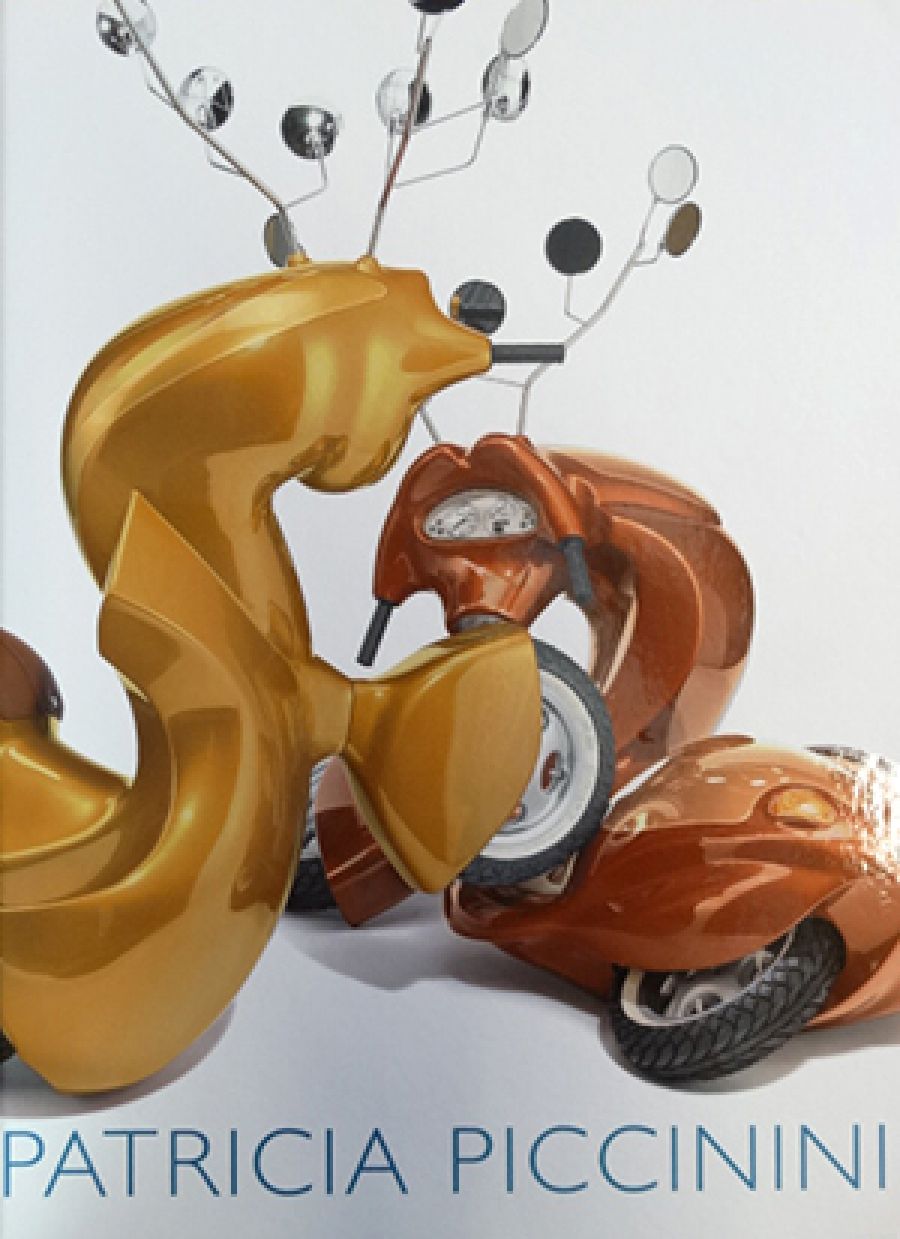

Highlighted in publicity material for the exhibition, the 2008 work The long awaited – in which a small child and an aged, sleeping creature embrace – appears to give overt expression to Piccinini’s view that we have ‘a duty of care to both the successes and casualties of technoculture’. The appealing (and notably non-confronting) image used on the cover of the handsome and weighty accompanying publication is the playfully combative Vespas The stags (2008), from the National Gallery of Australia.

In recent times, discussion about the necessity (within contemporary art discourse) of representing the artist’s voice has gathered momentum. Patricia Piccinini: Once upon a time ... includes an interview with the artist, in addition to a sensitiveessay by curator Jane Messenger (divided into ten readily digestible sections, with headings such as ‘Forming hybridity’, ‘Bioethics’, ‘Emotive automotive’, and so on). In the interview, we make the pertinent discovery that Piccinini is ‘drawn to Victorian social realism and ... its mixture of politics and sentimentality. It is a bizarre and unfashionable blend – literally “uncool” – but I find it quite powerful and it really informs my recent sculptures.’

Unsurprisingly, Messenger, who is the AGSA’s curator of European art, brings an historical European framework to her essay, variously invoking Renaissance images of the Madonna of Humility, Gustave Courbet’s representation of ‘real and existing subjects’, and British landscape architect ‘Capability’ Brown, in a consideration of the natural and the artificial. Acknowledging a divergence of ‘aesthetic and critical purpose’, Messenger draws an analogy between Piccinini’s motivation for ‘extend[ing] the debate [on issues associated with technological and genetic advances] into the emotional realm’ and the theories of artist Francis Bacon. ‘She wants us to receive her work through our senses – to discover meaning in sensation and through our emotional response.’ There are also (albeit fewer) contemporaryreferences, inparticular to American transgenic artist Eduardo Kac, who shares some of Piccinini’s conceptual preoccupations.

The large-format publication is lavishly illustrated with colour plates. Interestingly, Piccinini’s photographic images form a strong component of both the exhibition and publication. At the 1999 Melbourne International Biennial, a prominently positioned billboard – featuring Piccinini’s digital image Protein Lattice – Subset Red (1997), in which a beautiful model holds a rodent that is sprouting a human ear – signalled future directions. In its evolution from the early photographic images of actor Sophie Lee (1996) – depicted holding a designer baby/LUMP (Lifeform with Unevolved Mutant Properties) – to Nest’s (2006) anthropomorphic, golden machines, and Big Mother’s(2005) grotesque ape, who protectively cradles a human infant, the characterisation of the mother/nurturer and child – a leitmotif throughout Piccinini’s oeuvre – assumes surprising, strange, and sometimes confronting form. Roles become blurred in works such as Undivided (2004), in which the nature of the relationship between the small sleeping child and surrogate creature is ambiguous.

Providing a fascinating adjunct to Piccinini’s vision, Messenger has also curated the exhibition New Classicism (on AGSA’s upper level), which includes William Adolphe Bouguereau’s late nineteenth-century painting Virgin and Child and Marc Quinn’s Buck with cigar (2009).

Comments powered by CComment