- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In May 1990, Betty Churcher, then director of the National Gallery of Australia, Bill Wright, deputy director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and I stood outside what had once been the seat of Count Ostermann. This impressive building sits right off the Garden Ring, which surrounds inner Moscow. It is now the All-Russian Decorative, Applied and Folk Art Museum. All three of us, on our first trip to Moscow, were investigating the possibility of putting together a major exhibition of Russian and Soviet art.

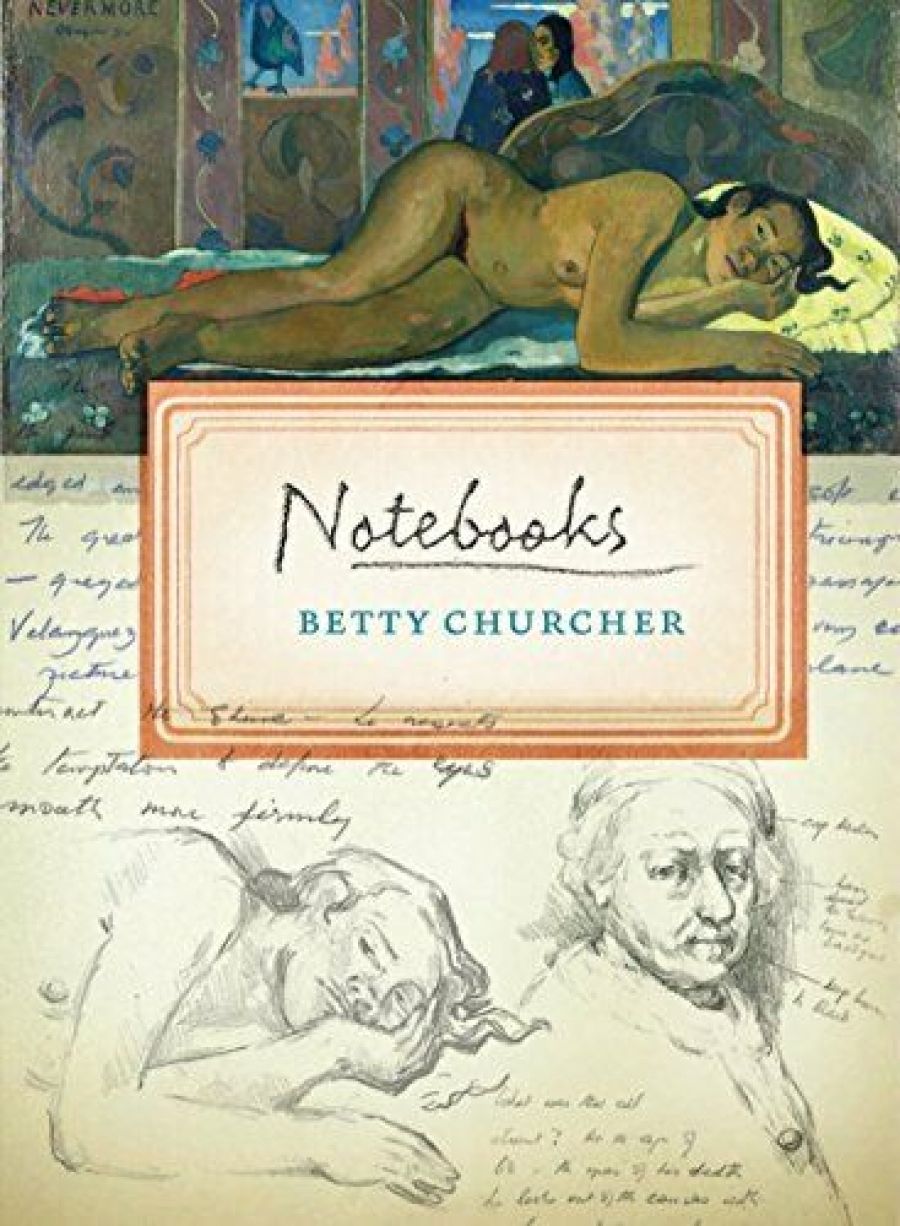

- Book 1 Title: Notebooks

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $44.95 pb, 256 pp

With our host from the Ministry of Culture, we entered the foyer and discovered much activity and a sense of excitement in the air. Our host announced that this was a special day as there was an opening that very afternoon of an exhibition of Russian icons. He invited us to return an hour later to take part. After seeing the fine collection of porcelains in another wing of the building, we made our way back to the foyer and were greeted by chords of liturgical chant floating above as we mounted the massive central staircase. The choir treated us to a brief concert, then we entered a series of large rooms hung with a dazzling array of some of the best icons in Russia. There had been no advertisement for this exhibition, yet the halls were filled with people who seemed to be in the know. As we moved from one icon to the next, it was clear that we had been given a remarkable opportunity to experience these powerful works.

Within minutes of starting our tour, Betty pulled out a notebook and her biro and started drawing elements in the paintings. She was mentally unpacking the elements that intrigued her about these marvellous panels. It was clear that she was drawing with a sharp eye and thinking with her pen about the way the artist built up the elements of each work. While both of us were standing in front of a stunning depiction of the resurrection, we found ourselves intrigued by the stylised folds on the garments of the witnessing saints. Rendered in gold, they took on the same quality as the cloisonné effect (or outlining of figures) that appears in some paintings by Matisse, which could be seen in the Pushkin and Hermitage museums. These were obviously paraphrased by Russian avant-garde artist Natalya Goncharova in her depictions of peasants. We wondered if this effect on these icons might have also helped fuel the development of ‘Rayonism’, the style conceived by Goncharova and her partner Mikhail Larionov in the early twentieth century. Such speculation, based solely on visual experience, was only possible because of the focus provided by Betty’s act of drawing what she saw.

In fact, Betty has used drawing, a skill she honed at an early age, as a habitual means of entry into many a masterpiece as she has explored art museums around the world. Now, with the aid of exploratory drawings from her notebooks, Betty has produced a book that summarises some of the wonders she beheld in these collections. She has also included a brief autobiography.

Betty Churcher was born in 1931 and raised in Brisbane, where she was captivated by a painting in the (then) National Gallery of Queensland: Blandford Fletcher’s Evicted (1887). This marked the beginning of a love affair with art, which sent her, with a Royal Queensland Art Society subsidy, to London in 1950. At this point she was enamoured with the work of Rembrandt. As she says, ‘Apart from the over-inked black-and-white reproductions in our textbook, William Orpen’s Outline of Art, I had only seen one original Rembrandt in the National Gallery of Victoria.’

In a frank narrative, Betty outlines her entry into the Royal College of Art, meeting her husband, Roy, an art student at the Slade School, and her subsequent life. That same frankness convinced her to give up creating art for other pursuits, but drawing never left her. The Churchers departed London for Australia after a tour of Europe in 1956, then between 1959 and 1966 she gave birth to four sons. From 1971 her professional career began its course. After teaching full time at Kelvin Grove Teachers’ College and completing a master’s degree at the Courtauld Institute at London University, she became Head of School at the Phillip Institute of Technology in Victoria. A visit from Janet Holmes à Court to the Phillip Institute led to Betty’s appointment as director of the Art Gallery of Western Australia. From Perth, in 1990, she was appointed director of the Australian National Gallery (now the National Gallery of Australia). Betty guided the national institution through tough times, as well as providing it with some of its highest-profile events, including stunning major exhibitions that earned her the title ‘Betty Blockbuster’.

Recently, Betty lost the sight in one eye and suffered macular degeneration in the other. However, displaying the strength of character that has always impressed, she resolved to return to London and Madrid in 2006, to have a last look at some of the paintings that have had so much meaning for her. This last encounter was to allow her to memorise these masterpieces so that she could relish them in recall.

Notebooks is a glossy, handbook-sized compendium of selections from Betty’s exploration of great paintings through her own drawings. Lavishly illustrated with both the paintings and her companion drawings, Notebooks also contains Betty’s commentary – observations of interest that reflect the same engagement she provided for the public with her series of short documentary explorations of works of art on the ABC called Take Five and Hidden Treasures.

In this beautiful publication, Betty Churcher shares her personal journey through some of the most intriguing and important masterpieces of painting in the history of Western art. It is a delight to hold, to read, and, most importantly, to look at.

Comments powered by CComment