- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Ornithology

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When the English zoologist John Gould died in London in February 1881, he was renowned for his scientific and descriptive studies, principally of birds – those found in his native Britain, the Himalayas, Europe, Australia, North America, and New Guinea – but also of Australian mammals. In the course of his self-made career, Gould produced forty-one large volumes, handsomely illustrated with 3000 plates. These were the work of several artistic collaborators, including, importantly, his wife, Elizabeth, and – early and briefly – Edward Lear, famous later in his own right for his limericks and as a masterly writer of nonsense verse and prose. In addition to his great published works of natural history, Gould was the author of many learned papers and the recipient of high honours from scientific societies. As a leader in his field, he interacted as an equal with aristocratic men of science and affairs; the members of the governing class of his day.

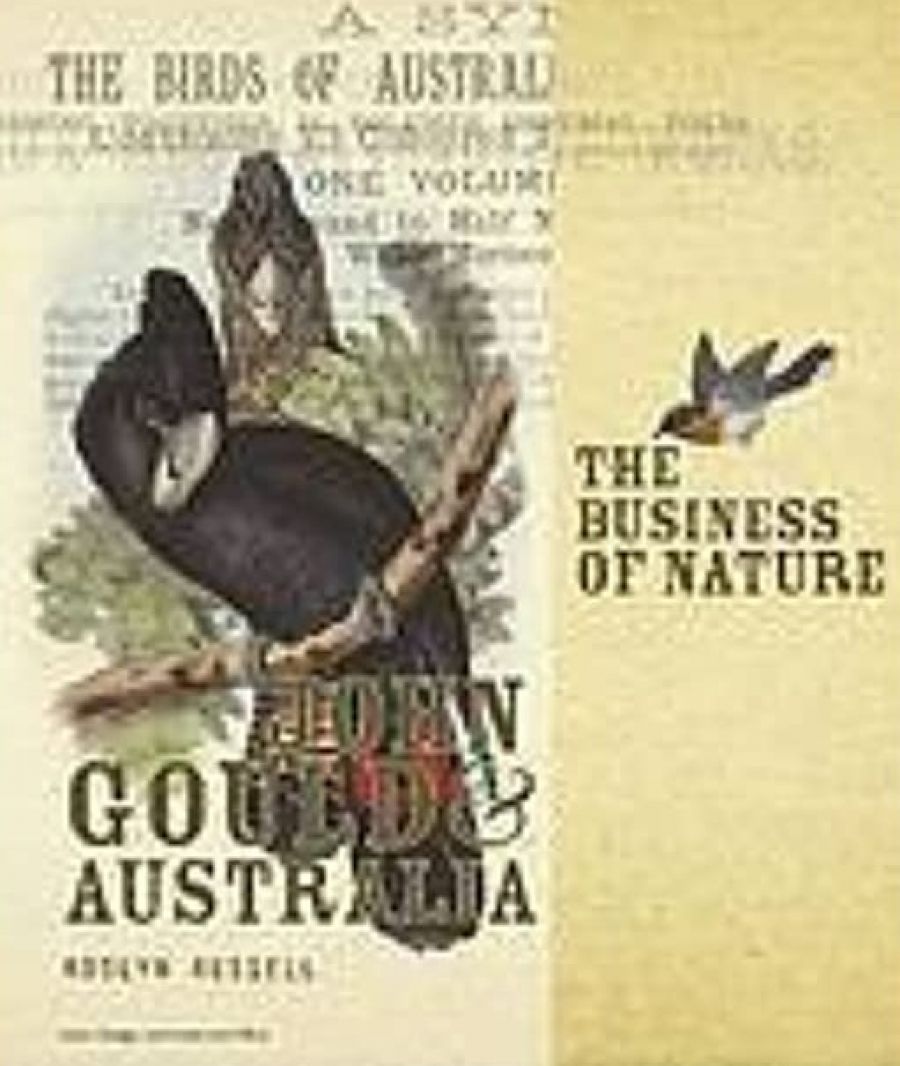

- Book 1 Title: The Business of Nature

- Book 1 Subtitle: John Gould and Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $49.95 hb, 224 pp

All this was an extraordinary achievement for a man born in modest circumstances in Lyme Regis in 1804, and whose formal education was slight. It was his early apprenticeship as a gardener working with his father that stimulated Gould’s interest in plants and birds, and that brought him eventually to the tough, disciplined, and single-minded interrogation of the natural world that defined his career and made his reputation and his fortune. With the publication of his work, Gould became knownboth as the ‘Bird Man’ and as an astute entrepreneur never shy in driving a hard bargain. Late in life, he cast a romantic light on what he remembered as his first encounter with the natural world. He wrote of his father lifting him by the arms to look into a nest of hedgesparrows in the family garden. Charmed and delighted by what he saw – a cluster of ‘beautiful verditer-blue eggs’ – Gould became ‘enamoured with nature and her charming attributes’. That impulse, he claimed, never lost its influence but kept on ‘acquiring new force through a long life’. When he died, his last great project – a survey of the birds of New Guinea and the adjacent Papuan Islands – lay unfinished. But Gould’s scientific reputation was secure, and remains so. Much later, the Australian naturalist A.H. Chisholm observed that in Gould’s extraordinary body of scientific work, he had created his own memorial.

In this new short study of Gould’s life and work, commissioned and published by the National Library of Australia, and deftly and elegantly written by the Canberra historian Roslyn Russell, the career and achievements of the venerable zoologist are revisited (as Russell indicates, Gould biography is a well-trodden field). The purpose here is not so much to dig new ground as to highlight the National Library as one of the institutional custodians (there are several of them) in this country of sets of the monumental The Birds of Australia (1840–48) and of The Mammals of Australia (1845–63). At the National Library, Russell has also drawn on other materials, including a long letter from Gould to the naturalist and explorer John Gilbert, one of those who guided him in Australia and collected specimens for him. Another of Gould’s supporters was Charles Sturt, with whom, in June 1840, he travelled through the ‘rich arboretum’ of the Murray Scrubs (now known as the Mallee). As her text and notes indicate, Russell’s sources extend beyond those of the National Library to other Gould repositories in England and to the State Library of New South Wales, which houses Elizabeth Gould’s Australian diary.

While her study spans the whole of Gould’s life and career, Russell rightly places her emphasis on his landmark Australian achievements. These were materially informed and enriched by the nineteen months that he and Elizabeth spent in this country from September 1838 to April 1840, separated from their young children who remained in England. Elizabeth’s life was cut short (she was only thirty-seven) when she died of puerperal fever in 1841, not long after her return from Australia and soon after the birth of her eighth child. That personal story, and Elizabeth’s singular role as the creator of some 600 drawings prepared for The Birds of Australia, are generously and critically assessed. The underpinning of Russell’s firm but subtle feminism ensures that biographical justice is appropriately and sympathetically dispensed (as it has been by others), where the monolith of Gould’s career and his work in succeeding years with the male artists he came to depend on for his later publications might otherwise have overshadowed his wife’s pioneering achievements.

The real service of this book is the glimpse it provides through a generous selection of reproductions from both the Birds and Mammals volumes, the works of art that make Gould’s volumes among the most handsome and distinguished of the great Australian plate books of the nineteenth century. For most lay readers, those volumes are generally inaccessible in the rare book repositories of the great research libraries, galleries, and museums, or are shown only occasionally in special exhibitions. Gould’s Australian volumes of birds and mammals may not have attained the majesty of John Audubon’s The Birds of America (1827–38), where life-size images on very large plates created ‘double elephant’ folios of truly noble proportions; but they, too, are visually stunning and a singular part of the record by which Australia’s unique fauna first came to be widely appreciated and understood in Europe as well as in our own country. In her graceful text, Russell pays tribute to these great volumes and brings a sympathetic understanding to their presiding genius. It is worth noting that a leading Sydney rare book dealer has currently listed for sale a splendid set of The Mammals of Australia offered with a copy of Gould’s earlier work A Monograph of The Macropodidae or Family of Kangaroos (1841–42) the work he commenced at the end of his Australian journey. Gould’s great enterprise reverberates still.

Comments powered by CComment