- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Val and Von

- Article Subtitle: Unconventional sisters in the tropics

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Valerie and Yvonne Cohen were ‘artful’ in more ways than one. Both sisters were artists, and most of their friends and lovers were artists. They were ‘artistic’, seeking an unconventional life. For years they spent their winters on a tiny tropical island. And they – particularly Val – were artful dodgers.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jane Sullivan reviews ‘Artful Lives: From Melbourne to the Islands: The artful lives of the Cohen sisters’ by Penny Olsen

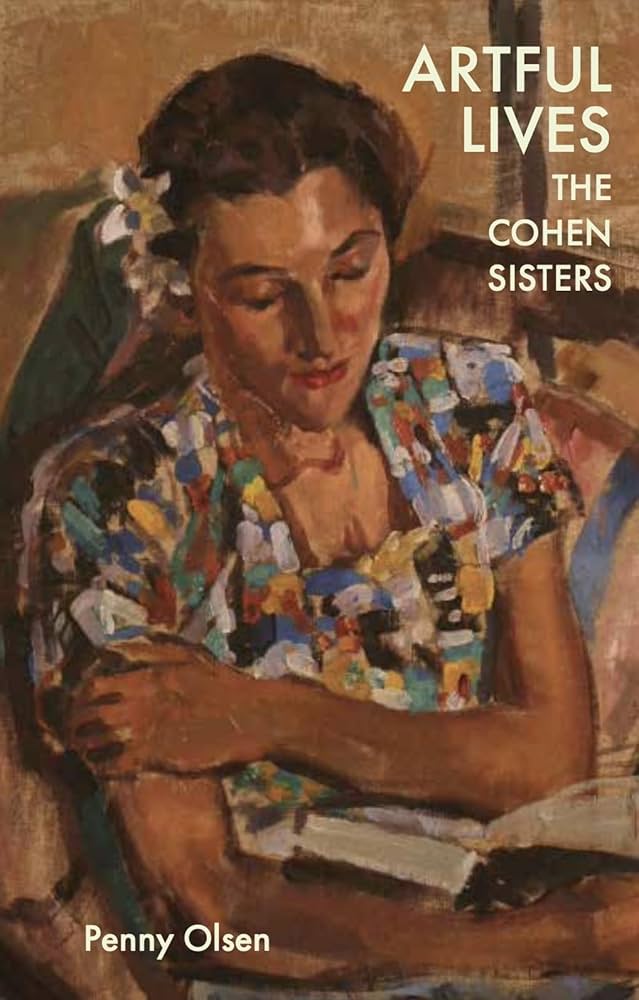

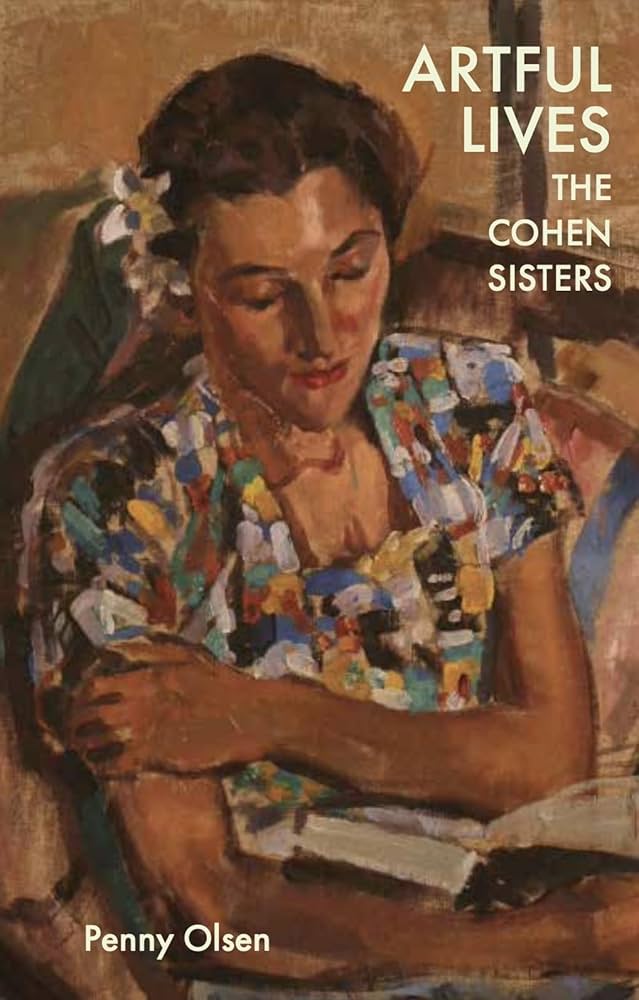

- Book 1 Title: Artful Lives

- Book 1 Subtitle: From Melbourne to the Islands: The artful lives of the Cohen sisters

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne Books, $39.95 pb, 303 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Olsen, an ornithologist and the author of more than thirty bird books, has wanted to write their biography for many years. She has drawn on a collection of pictures, photographs and written material, including Val’s articles for various newspapers and magazines, to present two different women devoted to each other, who, unusually for their times, managed to live their lives pretty much as they wanted. What they wanted was art, freedom to create, love, adventure, and highly romantic surroundings.

Their father was Morris Cohen, a well-to-do Melbourne businessman and a lively caricaturist. Despite this heritage, the girls didn’t seem particularly drawn to art. Tragedy struck in 1931, when Morris was killed in a boating accident on holiday in Tasmania. It was a horrendous ordeal for the teenage girls, who were on the boat with him when it was swept out to sea. They leapt overboard and swam ashore, but Morris didn’t make it: ‘A wave broke over the boat, and that was the last they saw of him.’

Their mother, Viva, was ‘completely lost’, Val recalled, and turned to her eldest daughter. What followed during the Great Depression years was an extraordinary series of extravagant and hedonistic voyages around the world by the bereaved mother and daughters. Australian gossip columnists were avid followers of the girls’ views on overseas fashions.

Val and Von were growing into society beauties, seemingly destined to marry and start families, but they weren’t having any of that. They decided to get serious about art through classes at Melbourne Technical College, but were soon bored with painting gum trees. Then Val escaped to Far North Queensland and discovered Dunk Island.

So began an enduring love affair for both sisters with that idyll of many painters, the tropical palm-fringed island home. They yearned for a simple life and had the means to get it: they bought little Timana Island, near Dunk and Bedarra, and hada bungalow built on the island so they could spend every winter there, fishing, tending a garden, and painting the surroundings.

Tropical beauty wasn’t the only attraction. The sisters were greeted on their visits north by two handsome, bronzed young men wearing nothing but sarongs. One was Hugo Brassey, a playboy who was developing a small resort on Dunk. The other was an artist, Noel Wood, living on Bedarra.

Many pages later we discover that Von fell in love with Noel, who was married and a new father when they met. His wife Eleanor doesn’t appear much in Val’s accounts. When Von fell pregnant to Noel, he returned to his family on Kangaroo Island, grumbling about ‘another bloody girl’. It is not clear whether there was an abortion or whether a baby was adopted, but ‘Von was deeply distressed and fled from the islands to Indonesia on a passing cargo ship’, Olsen writes. For the rest of her life, Von carried a torch for Noel.

Val was a tougher cookie. She was proud of her affairs, and eventually settled for marriage to a psychiatrist, Norm Albiston. She determined to win him the first time she saw him. Norm was an artist of sorts and a music lover: he played classical music on the piano wearing a monkey mask with a cigar between his teeth. He had a number of extramarital affairs which Val tolerated, even encouraged.

At moments like these I wanted to know more about the sisters’ emotional lives. What was the nature of Von’s romance with Noel, and why did it fall apart? Was Val really happy when Norm strayed? How did the sisters get on, in such a remote place? Did they quarrel? Did Von rebel against Val’s dominance? And how did poor Viva fare, anxious to be with her girls, but possibly feeling lonely when she joined them on their tiny island?

I can’t blame Olsen for refusing to fill these gaps. She is an old-school biographer who doesn’t speculate. She admits that she missed opportunities to collect some firsthand accounts. Mischievous Val was a thoroughly unreliable narrator. Her articles contain many contradictions. How much she romanticised her world we may never know.

Olsen doesn’t try to assess them as artists, though she includes contemporary reviews of their art. Most are favourable, if a touch patronising, with Von coming out a little ahead (she took herself more seriously as an artist than Val did). They exhibited regularly and their work sold. Recent feminist appraisals of women artists’ work have enhanced their reputation. But the sisters were never feminists. They didn’t believe that male artists were treated more favourably.

The narrative is filled with incident and intriguing digressions, but those emotional gaps remain. I came closest to the sisters not when they were on their island but when they were old ladies in Melbourne, the time when Olsen knew them best.

Comments powered by CComment