- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

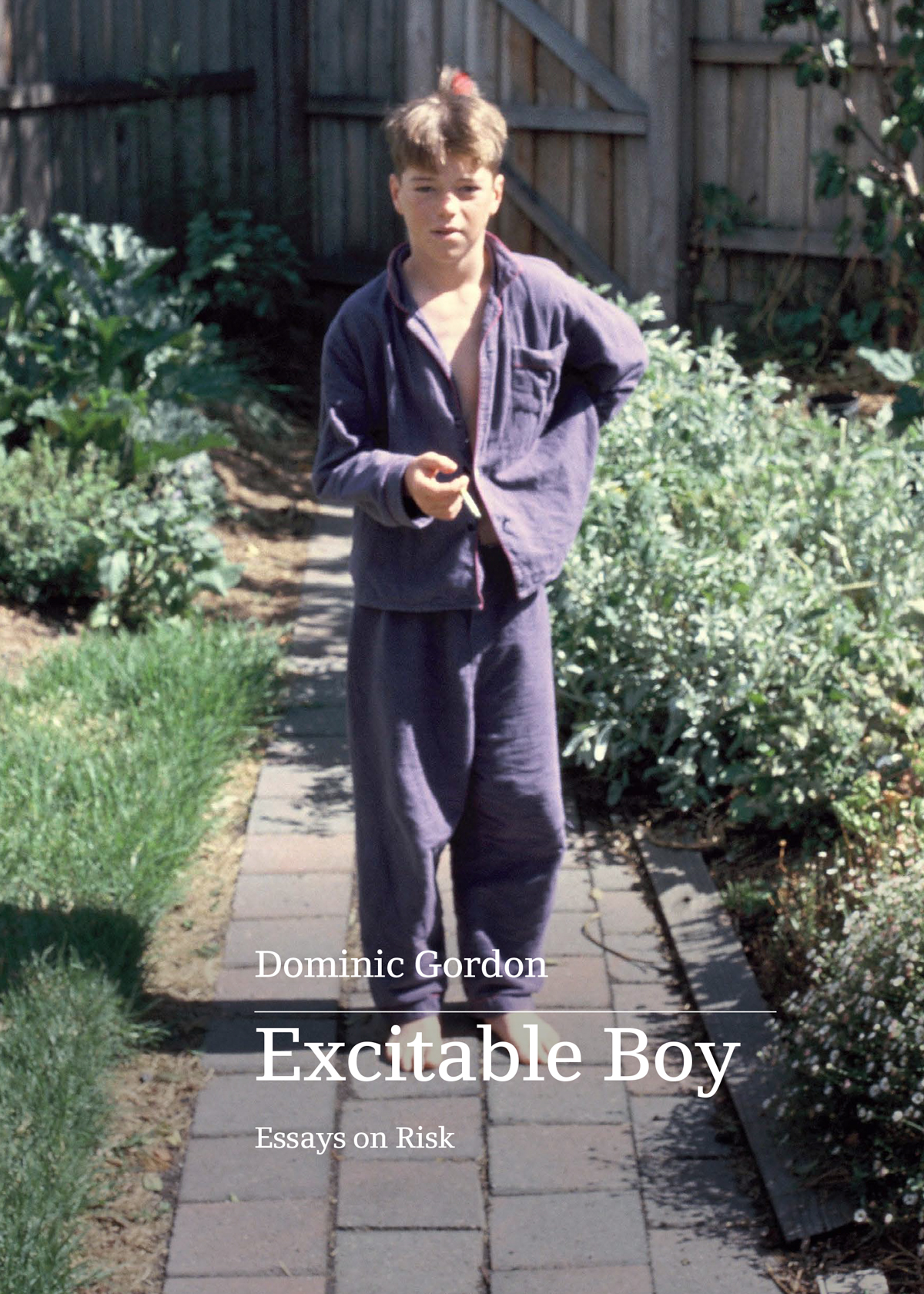

- Article Title: Scuzzball nihilism

- Article Subtitle: Transmitting the abject into art

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Loïc Wacquant has documented the migration of the term ‘underclass’ from its original structural meaning (as coined by Gunnar Myrdal) to contemporary usage, classifying those who exbibit a cluster of behaviours provoking anxiety or disgust from mainstream society. Australian publishing is, belatedly, providing opportunities for diverse voices across gender, sexuality, and race, but the underclass Wacquant delineated remains largely mute.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael Winkler reviews ‘Excitable Boy: Essays on risk’ by Dominic Gordon

- Book 1 Title: Excitable Boy

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays on risk

- Book 1 Biblio: Upswell, $29.99 pb, 173 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Taking himself as both subject and object, Gordon strives to collapse the distance between words and experience. The fluctuating energy of the writing, ebbing to ennui and cresting to chaos, does not merely echo but exemplifies what he is capturing. Sometimes the prose becomes overheated; as Gordon explains, ‘meth brain at full speed is Lance Armstrong on the sprint’. Sometimes an essay drifts, but then the life he was living, and the lives of his erstwhile comrades, were directionless, even nihilistic.

One of the book’s many surprises is that Gordon’s family ties are stretched but not ruptured. While Dominic ransacks shop tills and binges meth, his parents are at home watching Kieślowski and Buster Keaton movies. The removal of this most obvious motivation for his behaviour – broken family! – leaves the reader wondering about the possibility of psychological factors as a partial explanation. A weaker writer would have paraded pathologies for exculpation or cheap thrills. As Cher Tan writes in Peripathetic (2024), ‘we have seen how easy it is to leverage pain as a kind of currency.’

Gordon wears no labels. He offers no pat resolution, no moral lessons, no arc suitable for acclamation. The only concession comes in the short final essay, where he chooses to return home to his partner and baby rather than chasing a methamphetamine wipe-out. As redemption stories go, it is slight, but it signals progress in the author’s drive to integrate his competing strands of self. Throughout the book, we see him compartmentalising aspects of his life. For example, the pickpocket also loves watching vintage movies. The sometime streetfighter spends long hours reading in various public libraries. He describes his sexuality as straight, but for a decade he slaked his ‘chaotic’ sexual thirsts at gay sex lounges and beats.

The skill of hyper-observation developed as an opportunistic thief is equally valuable to the prose stylist. In a brief introduction, Christos Tsiolkas observes that there is ‘something almost frightening in the clarity and unsentimentally of [Gordon’s] storytelling,’ without ‘a hint of self-pity or sanctimony’. The writing is as pugnacious as Charles Willeford’s, the bathos and self-revelatory bravery recall Scott McClanahan, and Gordon’s hymning of the marginalised matches the Glaswegian grittiness of Ryan O’Connor’s The Voids (2022).

The collection begins with a whipcrack, ‘The Adelphi Hotel,’ a finely turned account of honour among pilferers. Equally effective, albeit in a different register, is the sardonic ‘Spiralling in Stream C: Slow Days in the Newstart Alcove’, in which the mature Gordon and an ensemble of Josef Ks struggle to navigate punitive unemployment processes. By contrast, the longest essay, ‘Coming of Age in the Wild West’, slows the pace and connects more obliquely with the stated theme, risk.

Readers eager for sociological insights into issues of masculinity and low-grade criminality may be frustrated by Gordon’s commitment to depiction, not explanation. He admits to enjoying ‘the power I could wield on the general public’, but otherwise his most pungent insight is that ‘[t]he heightened, insular nature of that world is also a good place to hide out, especially if there’s hectic subconscious pain in your soul’.

Shannon Burns’s indelible Childhood (2022), recounting the author’s emergence from utter neglect and occasional abuse to become a respected writer and academic, is already a classic of Australian memoir. Excitable Boy might be its rogue cousin, scratching and scrapping, chasing the chimera of an undivided self. Both books ultimately confirm the old-fashioned verity that love exists, and can provide salvation – familial, romantic, occasionally between friends or criminal acquaintances, and ultimately between parent and child.

Until love overcomes, other forces dominate. How else to explain the risks taken in the service of something so ostensibly unnecessary, for anyone beyond what polite society terms the underclass, as illegal painting of public property? ‘For young men looking for masculine expression, Graff had it all, and even though it was a deeply fragile, anti-developmental, addiction-incubating backward claustrophobic headfuck, everybody needs a rite of passage, right?’

Comments powered by CComment