- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: A. Frances Johnson reviews three books

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Time out of mind

- Article Subtitle: The art of the past in the present

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In E.L. Doctorow’s The Waterworks (his 1994 novel of post-civil war America), the narrator McIlvaine addresses the reader: ‘We did not conduct ourselves as if we were preparatory to your time. There is nothing quaint or colourful about us.’ Doctorow reminds the reader that our sense of modernity is an illusion. As Delia Falconer has eloquently noted apropos Doctorow’s novel, the contemporary historical novelist has a valuable role to play:

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): A. Frances Johnson reviews ‘The Engraver’s Secret’ by Lisa Medved, ‘Chloé’ by Katrina Kell, and ‘The Beauties’ by Lauren Chater

- Book 1 Title: The Engraver’s Secret

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $32.99 pb, 421 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

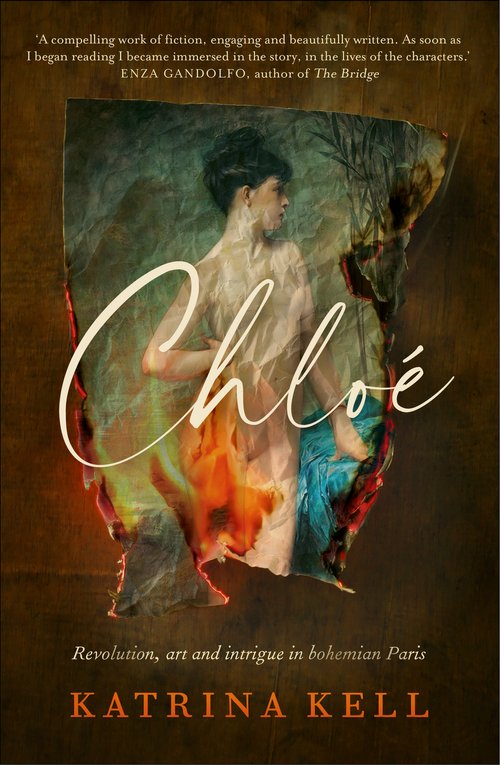

- Book 2 Title: Chloé

- Book 2 Biblio: Echo, $32.99 pb, 314 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

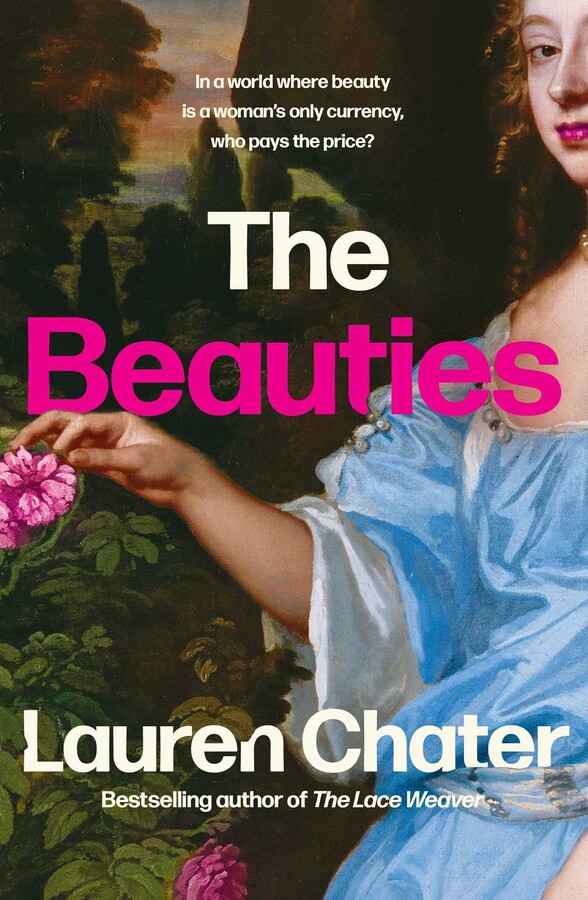

- Book 3 Title: The Beauties

- Book 3 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $32.99 pb, 375 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

This thought has antecedents in predominantly Western historiographies by Hayden White, Dominick LaCapra, and others. Notwithstanding problems of nostalgic or factual excess and traps of historical revisionism, effective throughlines between temporal constructs and a careful chronicling of the differences therein may be the foundation on which the moral and emotional force of Western historical novels depends.

McIlvaine’s metafictional intervention exhibits postmodern technique. There is still a bit of it about, say in Laurent Binet’s HHhH (2010). However, the singular realist historical novel, as the late, great Hilary Mantel has shown, exists alongside. And, as John Frow and others have noted, literary genres are mutable, conventions never fixed. Thus literary and popular historical fiction may meld fairytale, romance, adventure, science fiction, steam punk, and true crime, often in subversive ways.

To that end, three new Australian (art) historical novels fall under a broad label of historical romance. All three feature histories of art and artist protagonists.

History and art history departments get a bad rap in Lisa Medved’s début novel, The Engraver’s Secret (HarperCollins, $32.99 pb, 421 pp). Canadian Rubens scholar Charlotte Hubert, grieving the loss of her mother, finds herself on a short-term contract (that old bugbear) at the University of Antwerp. Here, intellectual property theft, attacks on women, and thefts of sundry antiquities provide an almost grand guignol setting for Charlotte’s archival discoveries. Letters obtained indicate a troubled relationship between Peter Paul Rubens and his master engraver, Lucas Vorsterman, and point to the existence of a cache of lost drawings by the Master himself. The hunt for this treasure provides dramatic impetus. Period scenes, variously set in the Spanish Netherlands and London in the 1620s and in 1675, counterpoint the hunt. Engraver’s daughter Antonia has cartographic gifts, predictably unsung. Her father offers encouragement, though this, alas, is spiced with unfortunate neologisms: ‘Despite your gender, you are just as capable as your brothers …’

Medved’s research is meticulous. The novel builds a dynamic montage between past and present without sentimentalising sisterhood across time. Studio practice in baroque Amsterdam fascinates. I appreciated the notes provided. But overblown campus intrigues weaken the denouement. The villain ultimately revealed is given minimal registration across this hefty novel but is responsible for nearly every bad event on the beleaguered Antwerp campus. Alongside, we learn early on that the head of history is Charlotte’s estranged father – an improbable backstory. This is a novel about cultural theft after all. Art is the thing and it was all that was needed. A little more Possession.

Georgette Heyer’s heyday is long gone, but the market is saturated with historical romances with readymade book-club questions at the back. It is a bonanza for commercial publishers, but less so for those publishing literary fiction. Romanticised female characters are uniformly feisty, spirited, liberated, or aiming to become liberated and destined to be, even secretly, an artist of some description. That ‘Anonymous’ was a woman is something this reviewer takes seriously. But the sassy heroines of these novels transcend unbelievable odds, embracing perfect heteronormative relationships while renouncing ye olde oppressions of class and gender on a penny purse.

Australian audiences may be particularly interested in Katrina Kell’s début novel, Chloé (Echo, $32.99 pb, 314 pp) which imagines the life of Marie Peregrine, model for the nymph Chloé, painted by French genre painter Jules Lefebvre in 1875. The iconic nude arrived in the colonies in 1879 and has hung in Young and Jackson’s Hotel since 1909. During the Great War, patriotic recruits toasted Chloé’s erotic profile before embarking for European slaughterhouses. The painting’s status is not entirely bound to salacious legend; Lefebvre, though no Manet, won the Gold Medal of Honour at the 1875 Paris Salon for this work.

Kell’s research is exhaustive. Commendably, there is no forced happy ending. Sketches of Marie come down to us from Anglo-Irish writer-artist George Moore’s memories of the artist-model at the Académie Julian. An autofiction short story fatalistically titled ‘The End of Marie Peregrine’ appears in Moore’s Memoirs of My Dead Life (1906).

In 1871, between 21 and 28 May, central Paris was incinerated and approximately 25,000 people massacred when French soldiers annihilated the short-lived Commune government, an event still commemorated as la semaine sanglante. When Marie and her Communard mother, Noemi, throw homemade paraffin bombs as citizen-soldiers, Noemi meets her maker, propelling Marie to find work as an artist’s model and to take art classes. The novel then moves between post-Communard Paris in 1875 and Port Fairy in the first year of the Great War, and thence to theatres of war and back to Paris, Melbourne, and Port Fairy again. Even Vincent van Gogh gets a look-in, taking a stroll through Montmartre with the homeless Marie. The painted nymph holds these settings together, but only just.

Marie is an affecting character, and snapshots of nineteenth-century artistic production compel. The brutal repression of the Commune is deftly conveyed. But the historical context becomes thin at times, to accommodate myriad shifts in place and time and excess characters. The Australian scenes, in solid vernacular, depict a poor fishmonger’s family implausibly obsessed with Chloé and her model. Disappointing, too, is the straight, school-marmish portrayal of legendary educationalist, communard, and anarchist-feminist Louise Michel, who runs a school and refugee asylum in the novel. Kell’s next novel? That might be interesting.

Lauren Chater’s fourth novel, The Beauties (Simon & Schuster, $32.99 pb, 375 pp), evokes the commissioning of the so-called Windsor Beauties, the models for which were aristocratic mistresses of Charles II. The portraits were executed by Dutch-born portraitist Peter Lely and his London-based studio colleagues, including formidable portraitist Mary Beale. They still hang at Hampton Court Palace. Lely, Beale, and Lely’s principal assistant Henry Greenhill (possibly based on artist John Greenhill – notes aren’t provided) are interesting secondary characters. Scenes reveal the gendered hierarchies, economies, and technical process of a bustling studio. Beale was the breadwinner for her family and she and Henry, differently struggling to emerge from their master’s shadow, give the novel flesh.

The novel’s press release states in caps that this novel has STRONG WOMEN AT ITS HEART. The especially strong woman is Emilia Lennox, whose husband’s lands and titles have been confiscated during the English Civil War. Reprisals and executions have followed since the restoration. A lonely young wife, Emilia spends secret hours in the dilapidated estate folly tower, communing with shelved artworks from the family collection as a kind of ersatz art training, subduing her ‘inner critic’ all the while. Descriptions of creative process often sound Instagrammable; this mars historical world-building, a sense of voices from the past made strange. Emilia soon puts art aside and travels to London to petition the king, who singles her out from a clamouring, ungroomed hoi polloi. A pardon for her husband will only come if she agrees to become the king’s mistress. Feisty Emilia stalls until her portrait is finished, failing to turn up for sittings and finding solace as a scene painter at the Fortune Theatre in a new company run entirely by women. No, this is not Carlton 1972. This is London 1660. While this was the year that the real Margaret Hyde was celebrated as the first woman to take to the English stage, playing Desdemona, a fully-fledged women’s company, replete with female carpenters, was too great a leap for this reviewer.

Of concern here is that subtle, complicating dialogue between past and present falls away when #MeCanDoAnything templates overly impose. When court Beauties commissioner Lady Anne Hyde nabs her duke, and Emilia reaches for her lover and ‘paints the first brushstroke on the canvas of her new life’, revisionism marries clichéd resolution. #MeUnconvinced.

Comments powered by CComment