- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hope and despair

- Article Subtitle: Amanda Creely’s furious new novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘But I think there’s sometimes more emotion in a whisper. It doesn’t cause a fuss.’ So says Teller, the narrator of Bendigo writer Amanda Creely’s novel Nameless. Her story, Teller tells readers more than once, is not nice. She is right: set in an unnamed and unrecognisable country and in a world that seems not to have sophisticated technologies for war or peace, Nameless is the story of everyday citizens facing an invasion by a hostile, brutal, and powerful neighbouring army.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Patrick Allington reviews ‘Nameless’ by Amanda Creely

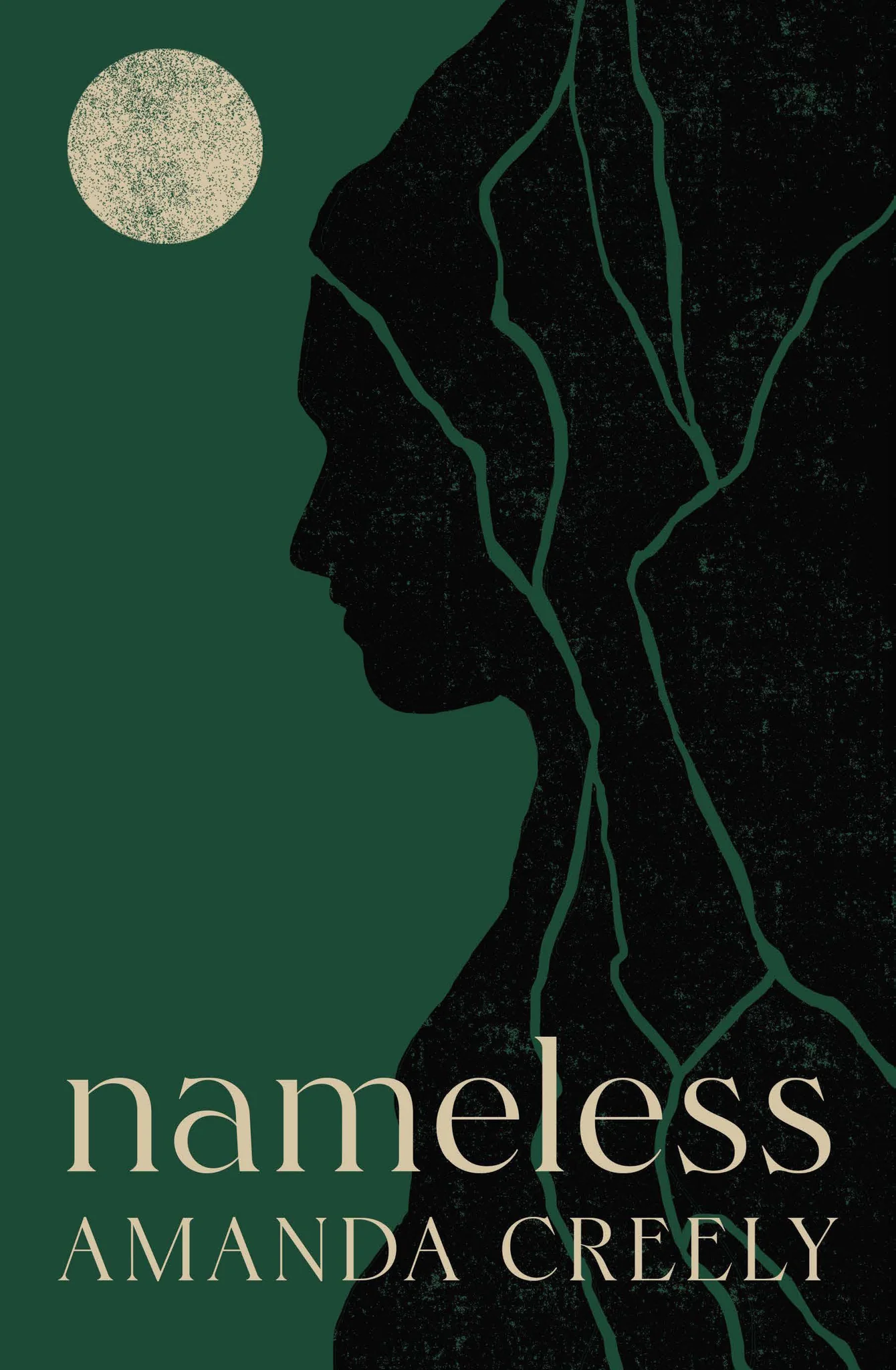

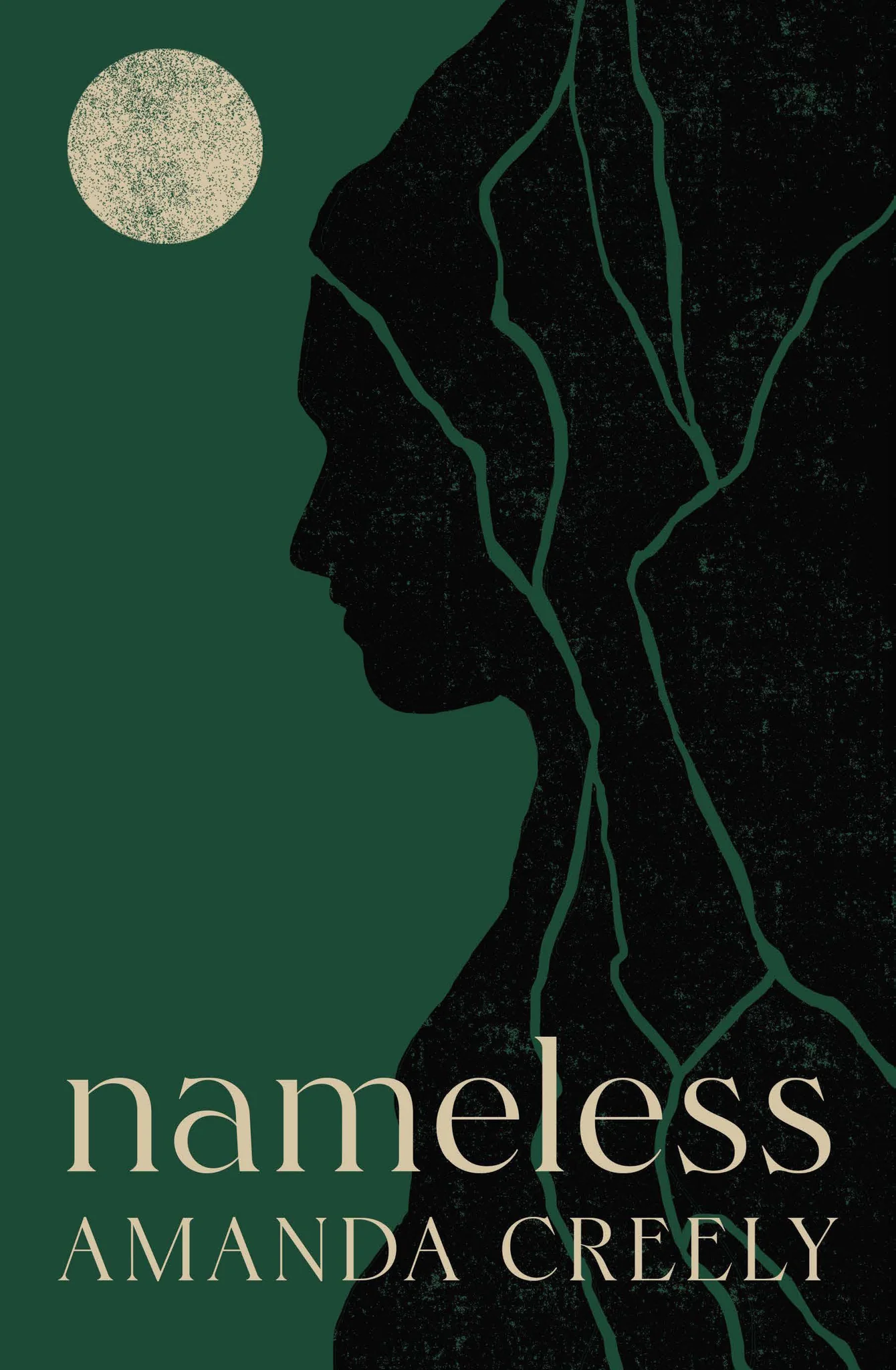

- Book 1 Title: Nameless

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $34.99 pb, 314 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Creely takes an allegorical approach to her storytelling, a choice hard to sustain for more than 300 pages. The plot is simple: one country invades another, many innocent people die in horrible ways, while others are imprisoned or forced into labour. Teller and Daughter find refuge on an island in a lake in a forest, among a small community of survivors. They become part of a resistance; they tend, to whatever extent possible, their broken hearts; they remember their dead or missing family. And they plan counter-attacks, though their numbers and resources are few.

Creely uses the bare facts of the invasion to invite the reader to dwell upon dichotomous choices, including despair versus hope, good versus evil, defeatism versus retribution, love versus hate, and love versus loyalty. While the plot nods only briefly to the machinations of geopolitics, it depicts wanton violence and cruelty unsparingly. In particular, Creely maintains a sustained and graphic focus – without allowing it to become gratuitous – on the sexual violence the invading soldiers inflict upon local girls and women, including Eldest.

Teller’s narratorial voice, matching the plot’s simplicity, is minimal, clear, claustrophobic, and raw. While her occasional deployment of metaphorical flourishes can be misplaced or jarring, there is something moving, for example, about the way she strains to describe generations of families as resembling trees: ‘and those trees like ladders that you ascend throughout the days of your life’. As the invasion becomes occupation, as the resisters do what they can, and as Teller’s account of all this builds towards its climax, the essence of the novel seems to metastasise from its focus on Teller’s inner world to a faster-paced plot that recounts various acts of survival and resistance. I found the novel’s first half more absorbing and original, but some readers will favour the accelerated momentum and the building of tension.

Creely juxtaposes the simple plot and prose with an excruciating, compassionate examination of Teller’s complex inner world. Teller sometimes whispers, sometimes wails. She has terrible dreams. She overthinks with painful exactitude and repetition, mixing grief, rage, bewilderment, and mental exhaustion as she endures her days. Mostly, she is reserved and careful, so much so that it is odd to hear her utter a rare profanity. But she is also prone to impulsive and dangerous acts. Most especially, she bears profound self-disgust that she has failed to do the impossible and save her family: ‘You know I’m not strong. You know I failed as a mother. You know I fall to pieces when adversity cuts at me.’ On the island, she fights her romantic feelings towards Rescuer, tempered by her commitment to her dead husband: ‘As good as Husband but not Husband’.

While a range of other characters are prominent in the story – especially Eldest, Daughter, Rescuer, a mysterious girl called Crow, a young man called Solder, and other survivors – readers come to know them mostly from Teller’s perspective, what she sees, thinks, wants, and remembers about them. The invading force never comes into focus, except through their actions and Teller’s fear and fury. The reader comes to know Invader as a man who enjoys leading by example, demonstrating to his men how to inflict pain and suffering. His deepest motivation, beyond conquest for conquest’s sake, is a mystery: what you see is what you get. He is present at key moments in the story, appearing with the convenience of a magic trick.

Perhaps Teller is speaking for Creely when she says, ‘I keep talking about hope, don’t I? Vacillating back and forth: hope gone for good, returning with a hip, hip hooray.’ Of all the dichotomies in Nameless, the most prominent, the most imbued with uncertain meaning and unanswerable questions, is that of hope and despair. Although this is a common theme in contemporary fiction, especially in the context of climate catastrophe and geopolitical uncertainty, Creely’s distinctive contribution is to intermingle, in sometimes discomforting ways, Teller’s personal mix of hope and hopelessness with the wider realities facing the people of her conquered nation.

Nameless was shortlisted for the Dorothy Hewett award, one of a bunch of publisher-run competitions for unpublished manuscripts in Australia. In setting the story in an unnamed and unrecognisable country, Creely universalises her furious anti-war, anti-violence, and anti-violence-against-women message. The war-related themes that underpin Nameless reinforce what history already tells us, despite our collective capacity to forget or want to forget: that leaders from different eras and political systems are capable of perpetrating mass violence and crimes against humanity; and that many nations and citizens are willing to ignore atrocities for reasons of expediency or self-interest.

Comments powered by CComment