- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Invincible summer

- Article Subtitle: A celestial journey to the limits of grief

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the joys of reading – and a point of difference from narratives told on the various screens we turn to for leisure – is imagining a story’s mise en scène. Our mental pictures (termed phantasia by a group of British neurologists) are a strange alchemy of images from our memories, thoughts, and dreams. Though visualisation is not a universal experience, many readers may comment that a book-to-film adaptation was ‘exactly as I pictured it’ or else ‘nothing like what I saw in my mind’s eye’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Naama Grey-Smith reviews ‘Bright Objects’ by Ruby Todd

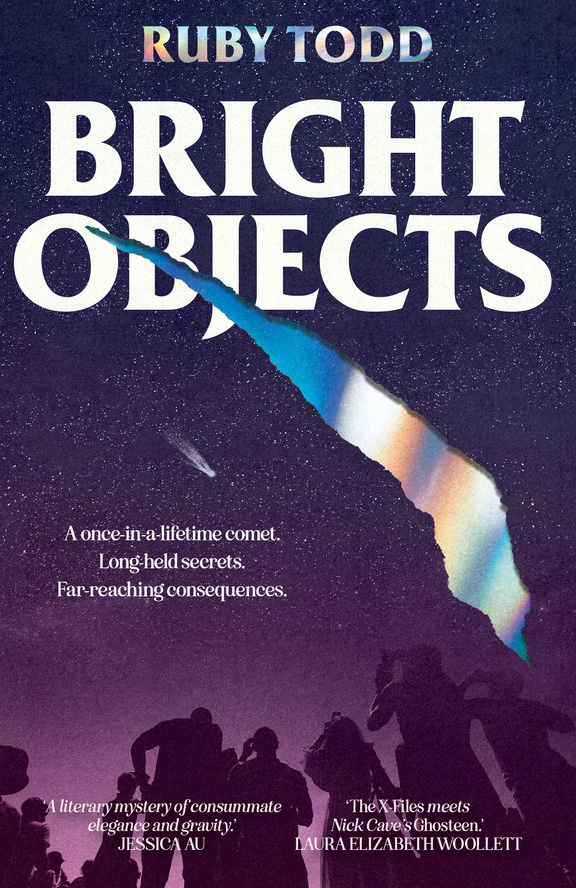

- Book 1 Title: Bright Objects

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 424 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Narrated in the first person, Bright Objects tells the story of Sylvia Knight, a young widow living in the fictional small town of Jericho, New South Wales. Grief-stricken over the death of her husband, Sylvia lives a cloistered life, working at a funeral home with ‘the tight-lipped atmosphere of wood polish and plush carpet and heavy drapes’. To avoid her own reflection, she has stuck over her bathroom mirror a poster of a seventeenth-century still life by Willem Kalf depicting ‘the remains of a luxurious meal abandoned in haste’. Time passes slowly for Sylvia, and her only sense of purpose – to find the hit-and-run driver responsible for her husband’s death – is frustrated at every turn.

The catalyst for Sylvia’s character evolution is the fictional Comet St John. The novel charts the comet’s passage in the night skies, commencing with its discovery in 1995 and concluding with its perihelion in 1997, when its proximity to the sun makes it brightest above Jericho. The approaching comet brings pilgrims into the small town and reveals the ‘various registers of fear, hope and hubris’ in the community, from the comet’s discoverer, astronomer Theo St John, to Jericho local Joseph Evans, whose messianic preaching attracts a dangerous following.

The work’s four-part structure – ‘Dark Skies’, ‘Closer’, ‘Arrival’, and ‘Departures’ – mirrors the comet’s celestial journey. In the novel’s prologue, titled ‘Divinations’, Sylvia explains that this journey is bookended by her own first and second deaths – exposition that establishes Sylvia’s narrative as bound to the comet’s, while also setting up the questions that drive the plot. If the narrative tension occasionally wanes on this orbit, it is of little concern since the writing remains unfailingly engaging and wise. It is also darkly humorous and witty: Sylvia observes new grief is ‘an alien planet’ and, in the same breath, quips that ‘it is not therapeutic for all in its exile to be faced with the finer decisions of commemorative slideshows and casket sateens’.

In a note to readers, Todd explains that the story draws on the real events surrounding the Heaven’s Gate sect in the United States during the appearance of Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997. However, Todd’s exploration of the significance of comets is much broader as she probes ‘the cultural, religious and scientific history of human beings responding not only to comets, but to the possibility of hidden or higher orders of reality in the universe’.

These philosophical investigations are the shining light of Bright Objects. Sylvia often wonders ‘how we might appear through the eye of a comet, making its icy passage through our galaxy, in a journey whose timespan couldn’t tally with the dimensions of our human lives’. She reflects on the rational self versus the shadow self ‘who wanted desperately to believe there was more than this: bodies bound to a continental crust, seeing out our time before necrosis, alone in space on a planet formed by accident’. She feels ‘the stirring of synapses in some region of my brain, the region still primed to look for meaning in happenstance’. Sylvia recognises that ‘For some without faith, and for mongrels like me, I supposed it would always be like this – a bereft and stumbling feeling, grasping now and then in the dark, but always returning to the conclusion that nothing about being here, alive in the world, would ever quite make sense.’

Appropriately, the novel’s twin epigraphs are from Seneca and Albert Camus. The first relates to comets, while the second is a declaration of resilience from Camus’s ‘Return to Tipasa’: ‘In the midst of winter, I finally learned that there was in me an invincible summer.’ (The two epigraphs share a connection to Rome – Seneca was a Roman statesman while the Algerian town of Tipasa, loved by Camus, is known for its Roman ruins – a connection that befits the novel’s study of mythology, with many celestial bodies named after Roman deities.)

Bright Objects offers a fine narrative and intriguing astronomical insights, but most compelling, for this reader, is its evocation of grief. Sylvia’s search for meaning in her ‘shipwrecked hours’ is deeply moving, especially as she reaches the limits of a life lived in mourning. It so happens that this book found me, the reader, in the midst of my own winter of grief, and for this its resonance was magnified. Readers who value a ‘naked and steely’ look into questions of meaning – those who don’t mind ‘peering through the crack between logical reality and oblivion’ – perhaps have most to gain from this profound, gentle, clear-eyed story. It is the story of someone who has known suffering, borne witness to it, and decided to keep going, meaning or no meaning.

Comments powered by CComment