- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Flies in the Nirvana’

- Article Subtitle: An illuminating and sisterly correspondence

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

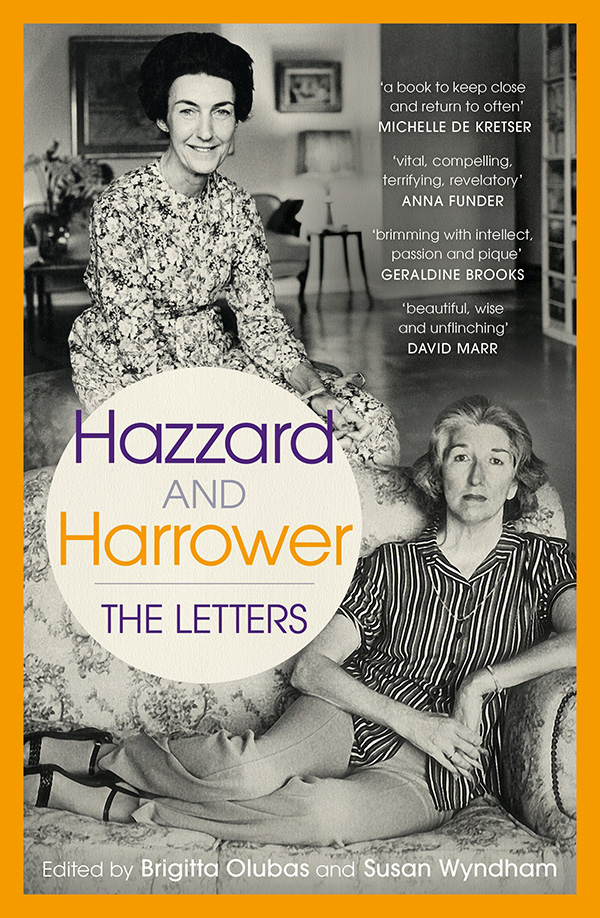

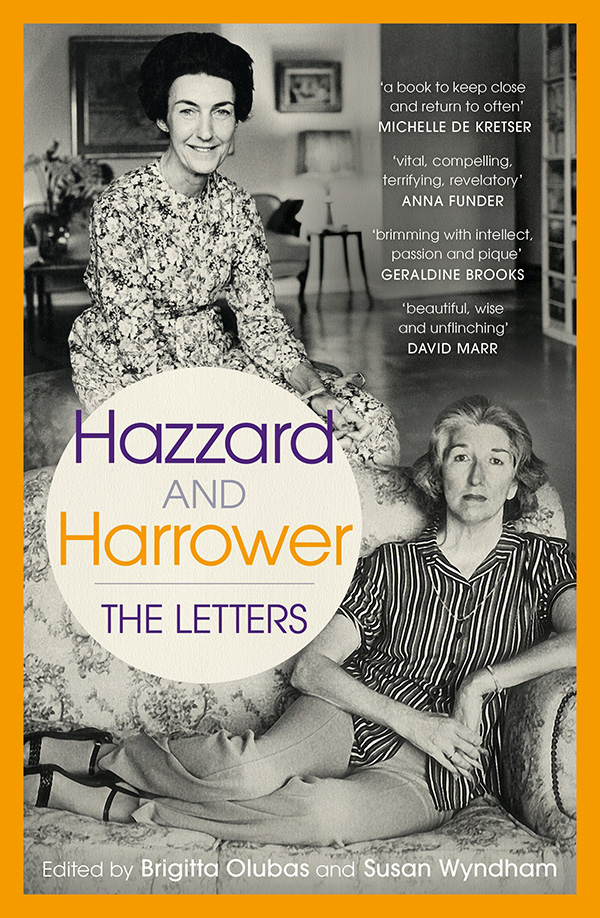

‘Everyone allows that the talent of writing agreeable letters is peculiarly female.’ So said Jane Austen in Northanger Abbey. Even allowing for Regency hyperbole, there is some truth in the sally. We think of the inimitable letters of Emily Dickinson, who once wrote to a succinct correspondent: ‘It were dearer had you protracted it, but the Sparrow must not propound his crumb.’ In 2001, Gregory Kratzmann edited A Steady Stream of Correspondence: Selected Letters of Gwen Harwood, 1943-1995. Anyone who ever received a letter or postcard from Harwood – surely our finest letter writer – knows what an event that was. She was nonpareil: witty, astringent, frank, irrepressible. Now we have this welcome collection of letters written by Elizabeth Harrower and Shirley Hazzard (unalphabetised on the cover, in a possible concession to the expatriate Hazzard’s international fame).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Peter Rose reviews ‘Hazzard and Harrower: The letters’ edited by Brigitta Olubas and Susan Wyndham

- Book 1 Title: Hazzard and Harrower

- Book 1 Subtitle: The letters

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 366 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

All letters withhold and dissemble to a degree, but these ones are surprisingly open, and mostly generous and encouraging – surprisingly so perhaps for two major writers, one of whom, already prominently married and situated at the outset, became internationally famous in her late forties, while the other, strikingly successful in the 1960s, retired hurt from the field and became almost anonymous until Michael Heyward of Text Publishing reprinted her novels, restored her reputation, and persuaded her to publish a late novel (all this well after the span of this book and the sending of that ‘light in the darkness’).

The editors – Sydney journalist-author Susan Wyndham and Hazzard’s biographer, Brigitta Olubas, a professor of English at the University of New South Wales – have turned 400,000 words of correspondence into ‘a more acceptable book length’. In a country with a more resilient biographical and epistolary tradition, we might have expected the entire correspondence, given the stature of these two writers. For the time being, we must make do with this entertaining and not insubstantial entrée.

It was Hazzard’s mercurial mother, Kit, who brought the two women together. Already, by 1966, Harrower was a kind of companion or carer to Kit (‘charming, lonely, and mentally fragile’, as the editors write in the Introduction). It would become a kind of lifelong responsibility – curse even – one that Harrower’s friend Patrick White considered a major factor in her lengthening creative silence. Writing to Harrower in 1971, he said: ‘Were alarmed to hear that Mrs Hazzard had broken a leg & was returning to Australia. Keep well away, or you’ll be landed with her for ever.’ White was a great admirer of Harrower, especially her fourth novel, The Watch Tower (1966) – ‘Harrower’s greatest achievement and one of the greatest Australian novels,’ according to the editors. Characteristically, White withdrew his own novel of that year, The Solid Mandala, so that his friend could win the Miles Franklin Award. (She didn’t.) In the end, White gave up trying to persuade her to write (‘Too many vampires make too many demands on her.’)

Hazzard’s conduct during the decades of Kit’s dependency on Harrower – which amounted to near-servitude for the Sydney writer – seems dubious and exploitative. Hazzard is a courtly tactician. In 1973, she writes: ‘Elizabeth, you have done so much and one blushes to ask further. Could you possibly hand in the application and ask whether questions might be relayed or answered by you? I would send the application to you; it would need my mother’s answers on a few dates …’

At times, the reader wonders why the moneyed Hazzard and her husband, Francis Steegmuller, who divided their time between Manhattan and Italy, didn’t simply buy an air ticket and fly to Sydney to alleviate the pressure, especially in 1980, when Harrower was once again left to mop up. ‘That you and Margaret [Dick] should have undertaken the monstrous task of closing up MM’s [My Mother’s] flat has been a sort of last straw of ultimate largeness of heart,’ Hazzard wrote with a kind of polished contrition.

We know from Olubas’s admirable biography, Shirley Hazzard: A writing life (Virago, 2022), that Hazzard’s filial relations were disastrous from the start. When Shirley was six or seven, Kit asked her to join her in putting their heads into a gas oven so that they could die together. Kit was the most capricious and ungrateful of mothers. The two writers were mystified by the turmoil of Kit’s domestic arrangements, and her emotional instability is a constant in the book – and mostly a unifying one. Kit was incurably peripatetic – fleeing Sydney, hating London, despising the Steegmullers’ tony life in Manhattan, then bolting back to Sydney.

For Hazzard, who rarely spoke of her mother with any fondness, Kit was ‘pretty close to unhinged a lot of the time … It is amazing how much horror, and strenuous horror at that, this little being managed to generate. Knowing her makes for a weird inimitable bond – like having been together in a shipwreck.’ Well into the friendship, Hazzard wrote: ‘You were utterly marvellous, as ever, to take MM for birthday lunch. I am sometimes desperate about her state [my italics].’

As Cicero reminds us, a letter does not blush.

Only rarely, and circumspectly, does Harrower presume to give her friend advice. In 1973, when Kit was being impossible and suicidal again, Harrower risked: ‘If you can give your mother something to look forward to, some idea that she’ll see you again, this will be what will settle her and calm her, I think.’ (How cautious and forbearing is that ‘I think’.)

Still, Harrower understood, better than most, the impossible side of ‘YM’ (Your Mother): ‘She can be exceptionally winning, and she can be merciless. They say that every difficult soul affects the lives of fourteen others.’

Along the way, there are wonderful surprises and insights. Writing about a play by Kylie Tennant, Hazzard notes: ‘I have always envied playwrights – dialogue is what I like to write, I sort of wait for it to come along on the page.’ Christina Stead (a vivid, poignant presence in the letters) is quoted as telling Harrower: ‘Patrick & Manoly [Lascaris] are your brothers.’ Hazzard describes Francis’s lifelong work on Flaubert: ‘Also Ms. pages of Mme Bovary fascinating to see – incredibly overwritten with every change, seething with intense intention!’ She declares that she wouldn’t stay in Italy if the Fascists (‘or for that matter Communism’) took over – ‘There is always a fly in the Nirvana.’ About Muriel Spark, who had introduced her to Francis, Hazzard is canny: ‘What a clever little creature MS is, when she can cut away all the rubbish. Good initials, too, for a writer.’

Hazzard is instinctively aphoristic: ‘People think they want tranquillity; but what they mostly want is for things to go wrong.’ Then she can be confidential: ‘What has any self-respecting person ever been, of recent centuries in their country but in exile? What has old Shirl ever been, in all her life, but an exile? What is any writer worthy of his salt but an exile.’

We forget what fine old lefties both women were. During Watergate, Hazzard writes: ‘Oh E, it is utterly engrossing, the unveiling of Nixon’s paranoia, his feuhrer (sp?) complex … The power these people have had, and the Nazism they expound …’ Harrower provides an anguished record of the Whitlam government. Her long letters of 17 and 30 November 1975 contain some of the great reportage on the Dismissal. Harrower was in Canberra on Remembrance Day, visiting Christina Stead:

Telephone rings. I hear Christina saying many times, ‘But that’s terrible. That’s terrible.’ Finally she came in. ‘What’s happened?’ ‘Malcolm Fraser is Prime Minister. Kerr has got rid of Whitlam.’ Horror. Horror and stupefaction. People very nearly fell down in the street with amazement and dismay. Manning Clark (our most splendid historian) said he was literally sick. Switched on radio which was dooming away in stunned voice. Chris offered gin, brandy, sherry, while I paced about holding head and listening to reports. Finally knocked off some Nescafe and took taxi to Parliament House. People surged there from everywhere. It was so AWFUL. Everyone was outraged. Our votes meant nothing. Moderate reform is not allowed to take place here. The new leaders came out on the balcony and laughed like Nazis.

From Olubas’s biography we know what a cultivated and bookish life the Steegmullers led in New York and Europe. Hazzard’s appetite for, and retention of, poetry (none of it Australian) was formidable. She knew reams of it by heart – loved it, lived it in a way. Famously, on first meeting Graham Greene, she capped a Browning quote for him. In New York the Steegmullers would think nothing of reading Thucydides or Dante or Tolstoy right through on their rare evenings alone (they were constant hosts).

Few of these heroic bibliophilic feats infiltrate Hazzard’s letters. ‘Shirl’ grows too fond and comfortable to feel the need to show off, as she often does elsewhere, however unconsciously. But the letters are full of authors and books – and frequent clippings. It is fascinating to keep up with what they are reading, sharing, discovering: Judah Waten, Edmund Wilson, Elizabeth Hardwick, Frank Moorhouse (‘trendy sex’) on Harrower’s part; Hal Porter, Edward Albee, Nadine Gordimer, even Thomas Pynchon and Arnold Bennett on Hazzard’s. Endearingly, she ‘cannot abide Woody Allen, nor get the point’. Now and then she is acerbic. In 1980, when Francis’s edition of the Flaubert letters appears, she writes of the reviews: ‘… since they would not be reviewers if they really knew anything, and since it is all favourable, no complaints.’

Hazzard is mordant about Murray Bail, who was then a trustee of the National Gallery of Australia: ‘Murray not only has no eye for painting; his eyes are closed. The visual arts in Aust are – what? – a busy desert.’ We find out why in the Olubas biography: a letter from Bail had led the Steegmullers to abandon their plan to bequeath their not inconsiderable art collection to the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

In 1979, Patrick White read the galleys of The Transit of Venus and was underwhelmed: ‘You are inclined to strike attitudes and pirouette around yourself, but only here and there.’ He went on, for the jugular: ‘… to me you do lead an especially charmed life writing away in the NY apartment and Capri villa while collecting your celebrities and charmers …’ This was too much for Hazzard. Writing to Harrower, she said: ‘It is, furthermore, dispiriting to find a really great man like Patrick writing the letter of any spiteful old quean.’ It was easy (still is perhaps) to parody the Steegmullers’ gilded existence – the ‘lovely life’ that Kit liked to mock, despite her reliance on their generosity.

The Transit of Venus, Hazzard’s magnum opus, came out in 1980 and survived White’s monstering. It won Hazzard the National Book Critics Circle Award and changed everything. Later, after Steegmuller’s slow decline and eventual death in 1994, The Great Fire (2003), her fourth and final novel, won the Miles Franklin Literary Award.

Never – despite the laurels, the distance between them, the brave solo travels in her latter years – does Hazzard stop encouraging Harrower or hoping for a new novel from her. It seems likely that she admired Harrower’s writing more than Harrower admired hers (with the exception of the early short stories published in The New Yorker).

There are hints, now and then, concerning the Steegmullers’ formidable social orbit in New York. When the Isaiah Berlins come to town, they expect to dine with them (‘in pursuance of Lovely Life’, Hazzard notes). One New Year’s Eve they head to the Met: ‘we were the guests at the opera in the box of the manager who is a chum of ours … [Joan] Sutherland, in glorious voice, proceeded to sing a high-camp and highly entertaining Daughter of the Regiment, to thunderous applause.’

Then there is this classic from 1982, when they hoped that Harrower might stay with them in New York: ‘The only problem is that most of their pictures will be out of the house – ‘we sometimes send them to the Metrop Museum summer loan show, particularly if we’re having a room painted or something of the kind.’

In the 1980s, there was a rupture in the friendship, doubtless traumatic for both women. For years the Steegmullers had begged Harrower to visit them in Italy or New York – as their guest. It is a kind of insistent refrain in their letters. In 1971, Francis, who often added fond postscripts to Shirley’s letters, wrote: ‘We must meet – it seems almost weird that we actually haven’t met!’ Hazzard was equally importunate, ending one letter: ‘More soon, dearest Elizabeth, and tremendous good wishes from us all. And utter determination on the Steegs’ part to arrange a reunion in ’73.’ (More intuitive hosts might have got the message and desisted, but not the Steegs.)

In 1984, Harrower – not an inveterate traveller, and wary about money – finally succumbed and met them in Rome. Harrower was tetchy from the start, complaining that her room at the Hassler Hotel, where the Steegmullers always stayed in Rome, did not have a view, and resenting Hazzard’s touristic bossiness (‘There you go again; I don’t accept orders’). Harrower stayed with them on Capri then decamped, skipping New York and returning to Sydney.

We know all this from Hazzard’s diary – not from the correspondence. Henry James wrote of the letters of Robert Louis Stevenson: ‘One has the vague sense of omissions and truncations – one smells the thing unprinted.’ The women hardly referred to the Roman debacle. And yet, rather movingly, a new kind of rapport entered the friendship. ‘Interestingly,’ the editors write, ‘from this coolness, this shifting of tone and focus, a new warmth develops, at least within the scope of the letters, which provide a less fraught account of their days and lives.’

Throughout, there are some choice episodes, none weirder than the one in 1973 when the Nolans visit Sydney, intent on monopolising Harrower. Cynthia Nolan takes great exception to Harrower’s decision to go on a cruise and refuses to see her, as Harrower reports to Hazzard:

I said what about relenting for half an hour and we’d talk of non-controversial things, but she said it would upset her too much and there we are. I’m sad about it, but she is fragile, and I’ve seen her ill, and down physically and psychically – all ways. She thinks I am used, apparently, and credits me with a rather frailer and simpler characters than I possess.

Frail or simple neither of these artists was. There are some classic letters here that would be worthy of a second edition of The Oxford Book of Australian Letters, should Brenda Niall be persuaded to revisit it. One example is Hazzard’s gleeful, excoriating letter of 15 May 1982 in which she describes a rancorous dinner that Sumner Locke Elliott was forced to endure chez Patrick White. When Sumner flees, White appears on the verandah and calls out ‘Come back’. Sumner does, sensing remorse on White’s part. ‘Whereupon Patrick yelled, “Not you! The dogs!”.’

Hazzard and Harrower teems with gossip, whimsy, illuminations, reassurance, disappointments – and a rather Australian kind of informality and sisterliness, perhaps not something we might have expected from Shirley Hazzard.

Comments powered by CComment