- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Williams and Soeharto

- Article Subtitle: Australia's most vital diplomatic asset?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Thirty years before the Australian career criminal Gregory David Roberts travelled to Bombay and sought to make for himself, in the words of critic Peter Pierce, ‘a good Asian life’, another socially alienated Australian pursued such a life, in Indonesia, one which in its own way was as remarkable as that novelised by Roberts in Shantaram (2003).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Nathan Hollier reviews ‘Occidental Preacher, Accidental Teacher: The enigmatic Clive Williams, Volume One, 1921-1968’ by Shannon L. Smith

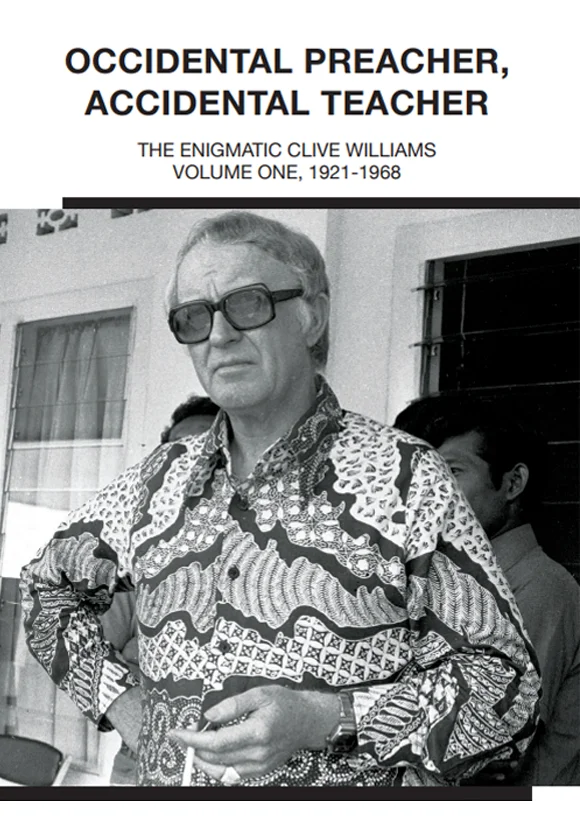

- Book 1 Title: Occidental Preacher, Accidental Teacher

- Book 1 Subtitle: The enigmatic Clive Williams, Volume One, 1921-1968

- Book 1 Biblio: Big Hill Publishing, $34.99 pb, 252 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Newly independent Indonesia had identified English, rather than Dutch, as the international language for its people, and by September 1960 Radio Australia received requests for and delivered some 260,000 booklets to accompany the English lessons it had begun broadcasting in October the previous year.

From the late 1950s, Williams developed a special teacherly rapport with Tien Soeharto, the wife of a rising army officer. He taught Soeharto as well and would become, for him, a supremely trusted confidant, adviser, translator, and intermediary: an honorary member of the family and, in his biographer’s estimation, ‘Australia’s most vital diplomatic asset anywhere in the world’ from the 1970s to the 1990s.

After Soeharto became acting president in 1966, Williams moved into an adjoining house in Jakarta. The properties were connected, meaning that Williams had unfettered access to the new ruler. As Smith shows, this relationship was important for Soeharto in a personal but also in a public sense. Most crucially, as Soeharto sought to formulate an economic plan (based on US aid), derive constitutional arrangements through which he could become and remain president, and put forward a credible stance for Indonesia in world affairs, Williams, as his intermediary, ‘divulged vital information that would have a significant influence on US foreign policy towards Indonesia’. The United States, like its ally Australia, would support and buttress the Soeharto regime, before finally withdrawing its support and ending Soeharto’s reign during the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s.

Thus, through his closeness to and influence on Soeharto, a major figure on the world stage, Williams can also be seen to have been a significant figure in world history in his own right; one who, through both choice and circumstance, kept determinedly in the shadows. He is only now being drawn out by his equally determined biographer to receive his due credit.

But what credit is that, exactly?

From one point of view, this study by Shannon L. Smith, the first of two volumes, is a most admirable undertaking. It is based on voluminous research, proficiency in Bahasa Indonesia, and the energy and single-mindedness to proceed with publication and distribution without fully professional editorial or publishing assistance. The story related, full of interest and colour, adds to our knowledge in a number of areas, especially to our understanding of what Soeharto and his circle knew of the 30 September movement in advance of its attempted coup: more than had been previously realised.

From another point of view, this work is let down somewhat by the writing and editing, some tangential excurses (into the history of the JWs for instance), valuable narrative threads left hanging (such as the experience and even first name of the Bahasa Indonesia-speaking ‘Mrs Gorton’, who impressed her hosts greatly on a state visit), and questionable historical interpretation. More importantly, it is undermined by an insufficiently critical attitude towards a still dominant Western interpretative framework in which Soeharto’s bloody rise to decades of oppressive authoritarian power is perceived as the result of social dynamics that were internecine, inevitable, and, ultimately, good – or at least for the best. ‘The outcome’ of the Soeharto coup, or counter-coup, Smith writes, ‘came as a relief to the Australian Government’ because the ‘regional neighbourhood was undergoing widespread change and disruption throughout the 1960s’.

For Smith, who notes that the nation’s first free elections, of 1955, were primarily a contest of (Sukarno’s) Nationalist, Socialist, and Communist parties, Soeharto’s ‘authoritarian government’ from 1965 ‘was considered by some as one of the most deadly and corrupt, and by others as one of the most economically and developmentally successful in modern history’.

The possible value of the alternative path to development for Indonesia, suggested by the widespread hunger for English at the start of the 1960s, the popular political activism of the Sukarno period, and that president’s spurning of US economic aid is not registered. Nor is the full human cost of the decades of social, cultural, and educational retardation that followed on from the hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, murdered by the Soeharto regime.

This brings us back to Mr Williams and his good Asian life.

For Williams, living ‘a comfortable bachelor lifestyle in the foothills of Semarang’, as Smith writes, there was clearly pleasure, interest, and human connection. A German Jesuit priest recalled coming across Williams, ‘a very fat man, sitting there and treating us to steak’, in 1965. He travelled in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Europe, buying branded bags and accessories for Tien and taking large amounts of cash for depositing offshore. He was a vital conduit between Soeharto, US Ambassador Marshall Green, and other US diplomats, and to a lesser extent between Soeharto and the Australian diplomatic corps: part of a recognisably boozy, insular expat world memorably portrayed in Blanche d’Alpuget’s Monkeys in the Dark (1980), from which Williams socially kept a marked distance. A central point made by Smith is that Australia’s representatives were slow, if not derelict, in grasping the value of this Indonesian-based asset.

President General Soeharto of Indonesia and his wife, Madame Tien Soeharto, with Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh at Buckingham Palace before a State banquet in their honor, 1979 (PA Images/Alamy)

President General Soeharto of Indonesia and his wife, Madame Tien Soeharto, with Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh at Buckingham Palace before a State banquet in their honor, 1979 (PA Images/Alamy)

In obtaining such closeness with Soeharto – a man who was, in addition to being an admirable people manager, clear-eyed diplomatic strategist, loyal family man, and golfing enthusiast, a mass-murdering, mass-oppressing, mass-scale embezzler – did Williams also obtain, in the end, a sense of deep personal satisfaction, accomplishment, and equanimity, as Jean Piaget suggested a person, towards the end of life, might?

We can wait and read what Smith finds, in the second volume; but it does seem that Williams’s own anti-Enlightenment belief system made him well suited to psychologically accommodating the extraordinary role and position that fate afforded him. Following his abandonment of JW puritanism, Williams’s religious yearnings found a home in Javanese spiritualism; Smith considers, intriguingly, that Soeharto may even have looked up to Williams as a spiritual leader. ‘At most’, as Smith writes, Williams ‘was probably indifferent … [to] the slaughters that occurred’.

Missing, here, is the kind of awareness of moral complexity and contingency, within human life, shown by the criminal but world-wise and philosophical narrator of Shantaram. Nonetheless, Occidental Preacher, Accidental Teacher is a valuable addition to scholarly understandings of the Soeharto regime.

This article is one of a series supported by Peter McMullin AM via the Good Business Foundation.

Comments powered by CComment