- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Both portrait and polemic

- Article Subtitle: Boris Frankel’s genre-bending work

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I first met Boris Frankel when he was a thirteen-year-old, in the pages of a file at the National Archives of Australia. I was working on Russian migrant families in Australia that decided to return to the Soviet Union, but then tried to come back to Australia. Boris and his sister Genia had travelled more than 1,500 kilometres from the Crimea to Moscow, alone, in 1959, in the hopes of persuading British authorities to allow their return to Australia. It was a remarkable story: two teenagers who negotiated Soviet bureaucracy and surveillance, made an impassioned plea, and secured the support of a British ambassador. The file even contained letters the children had written to Prime Minister Robert Menzies – their own, teenaged voices. Letters like this are a historian’s dream: I felt I had got to the heart of the story. And yet, in Boris Frankel’s historical memoir, No Country for Idealists, I saw the trip to Moscow anew. In the texture of Frankel’s narrative – their Siberian cabin-mate on the train journey (named Rasputin!), the ambassador’s chef who cooked them breakfast – the wonder of the journey emerged afresh.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ebony Nilsson reviews ‘No Country for Idealists: The making of a family of subversives’ by Boris Frankel

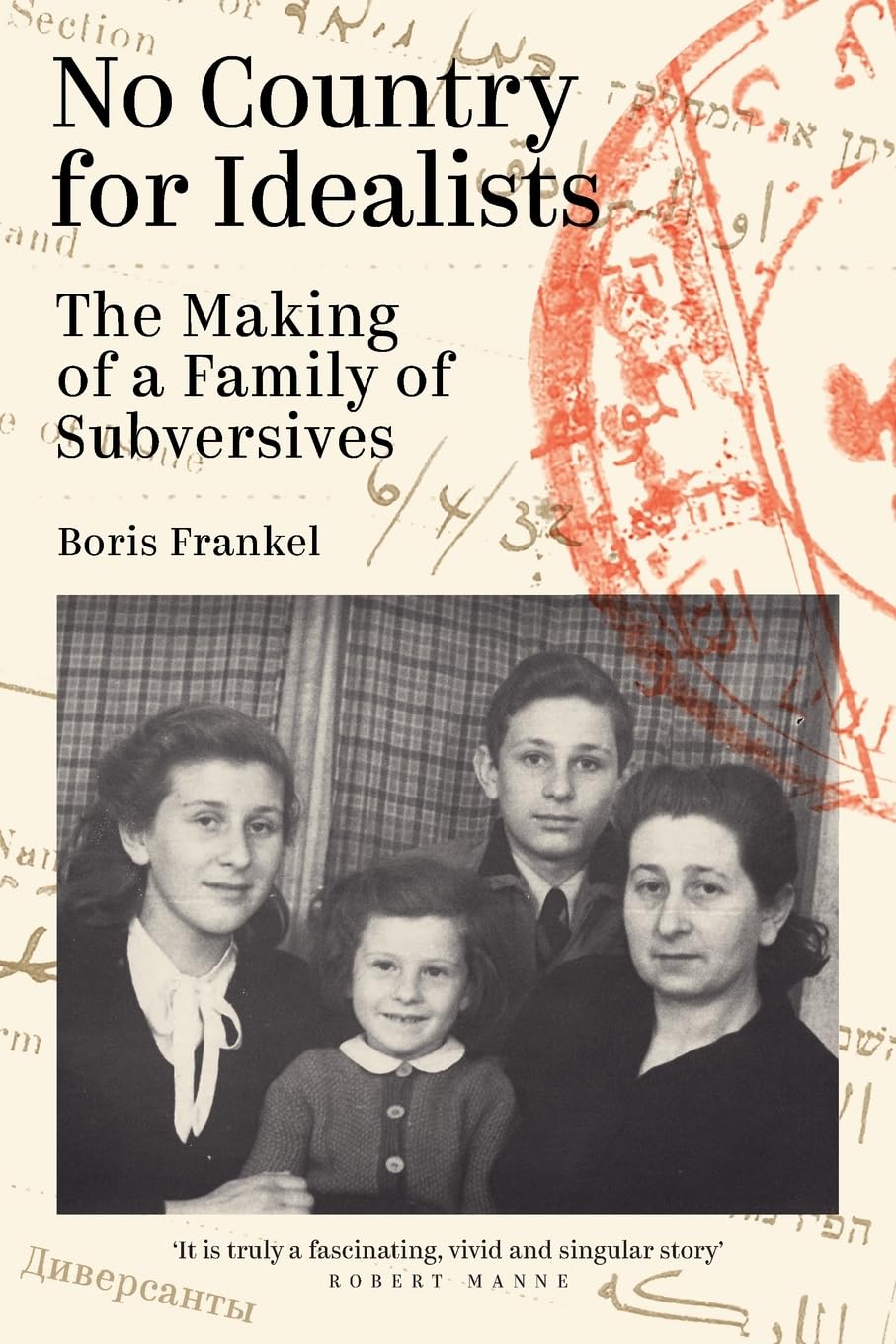

- Book 1 Title: No Country for Idealists

- Book 1 Subtitle: The making of a family of subversives

- Book 1 Biblio: Greenmeadows, $34.99 pb, 384 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Frankel describes the writer’s mistaken belief ‘that whatever is written down on paper – whether personal letters or official records – is equivalent to the truth’. Perhaps this was my trap, as a historian. No Country for Idealists is something of a genre-bender: part memoir, part family history, part political commentary. It is not an academic text as such, but Frankel is a social theorist and political economist, and writes like one. Alongside more typical reminiscences of migrant life, Frankel provides commentary on the limitations of his own memory, and asides regarding politics and international relations. In my research, of the handful of other families who crossed the Iron Curtain eastward and then attempted to return to Australia in the 1960s, the Frankels are the only one that succeeded.

Abraham Frankel, Boris’s father, was the one who instigated their move to the Soviet Union. Abraham was born in the Crimea, and his family fled the violence and hunger of civil war in 1920, settling a few years later in Tel Aviv. Tough economic conditions following the Depression saw Abraham uprooted again; he moved to Australia in 1938. He would meet Boris’s mother, Tania, in Melbourne in 1940. She had migrated from provincial Poland in 1937, towards better economic prospects and away from growing anti-Semitism in Europe. None of her family would survive the war and the Holocaust. The Frankels’ fairly representative story of migrant life in suburban, 1950s Melbourne – securing a home, raising children – is punctuated by less typical political activity and spies. Abraham’s involvement with the Communist Party, both parents’ engagement with the left-wing Australia-Soviet Friendship Society, and contact with Soviet officials (including Vladimir Petrov) made the family a security threat in ASIO’s eyes.

Abraham soon decided that their best option was returning to the Soviet Union – a workers’ paradise and a fairer, more tolerant society. The rest of the family was less enthused, but they decided to stick together. Leaving Melbourne in 1956, Abraham told waiting reporters that they had not been coerced into returning: rather, ‘I’m homesick – yes, that’s the word.’

His Soviet homeland was not all that he hoped, however – neither as they experienced it while living with Abraham’s sister in Baku, nor when they moved to his hometown in Crimea. Abraham struggled to find housing and work. Tania soon refused to leave their apartment, and the children did not attend school. They began applying to return to Australia almost immediately. Between Australia’s reluctance and Soviet attempts at obstruction, it took three years for just Tania and the children to be accepted for migration. They would have to leave Abraham behind. The Frankels were not reunited for a further three years, until ASIO’s Director-General, Charles Spry, reluctantly withdrew his security objection to Abraham.

This is a memoir of life during the Cold War. Frankel’s unique experience allows him to bring colour to life on both sides of the Iron Curtain. He does show how harsh Soviet life could be. The Frankels’ disillusionment creeps in quickly: from Abraham waving and calling ‘privet!’ (hello) to stony-faced Soviet citizens at the dock as they arrived, to a harrowing few nights in Moscow’s Kazansky station, awaiting train berths. There are cramped, shared apartments and the trials of a gulag returnee whom Abraham met on the train to Baku. But Frankel’s Cold War also included lighter moments. There was the time a teenaged Boris was almost reported as the victim of a KGB kidnapping in London, when he was, in fact, attending a double feature at the cinema. There were Abraham’s Soviet co-workers producing a secret album of photographs for him upon his departure for Australia. There was hardship in Australia, too. Without Abraham, particularly, the family struggled to earn enough money to stay afloat. Their furniture was paid for by Boris’s windfall in a work footy tipping competition – a sport about which he knew next to nothing.

It was a staple of Cold War politics in the West for each side to claim that the other was the ‘real’ oppressor of freedom. Cold Warriors derided the totalitarian communist bloc, while Western leftists attacked their own governments’ regimes of surveillance. Frankel was well placed to compare the two. He notes many similarities between the Soviet Union and Australia at the height of the Cold War panic. Not everyone in Menzies’ Australia experienced surveillance so directly, but the Frankels received significant attention from ASIO. His memoir also provides glimpses of everyday life under surveillance, of both the significant and more mundane impacts of government monitoring. Frankel is understandably critical of ASIO – its work, its efficiency, and its mandate in general. The ASIO officers in the book emerge as harsh, unsophisticated hacks. Although his critiques are occasionally overly definitive, I can relate. When I applied to have Abraham Frankel’s ASIO files released, I was initially told there was no file on him. After some protracted correspondence (and insistence on my part that the file did exist), he was located under the wrong date of birth and the first name ‘Sasha’.

While No Country for Idealists can occasionally feel like a polemic, it is also an engaging portrait of a family. Abraham looms large in the files assembled by ASIO, Immigration, and External Affairs – and in the minds of ASIO and Australian government officials, it seems. Frankel’s book restores his mother to the picture. Tania emerges as strong-willed, capable, and interesting. It may have been Abraham’s decision to move the family to the Soviet Union, but Tania – and her children – did much to secure their return to Australia. Frankel is both candid and gentle in his treatment of his parents. Abraham and Tania appear as intelligent, headstrong, occasionally foolhardy, flawed, yet very warm figures.

From the fields of Tel Aviv, to seaside St Kilda, the old city walls of Baku, and the frozen shores of Kerch, No Country for Idealists is a sprawling, spacious tale. Frankel ultimately concludes that his family was richer for its experiences – and this reader was richer for his account of them. Frankel’s memoir brings something that the file could not. It is a warm, lively account of life during the Cold War, on both sides of the Iron Curtain, and of a remarkable family navigating border regimes, political systems, and surveillance.

Comments powered by CComment