- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Limitless possibilities

- Article Subtitle: A magisterial study of revolutionary France

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On 27 August 1783, Jacques Charles launched the world’s first hydrogen balloon flight from the Champ de Mars (now the site of the Eiffel Tower). He excluded his rival Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier from the ticketed reserve. Then, on 21 November, Charles and another ‘navigateur aérien’ made the first manned flight, landing thirty kilometres north of Paris. Montgolfier was invited to cut a ribbon as a gesture of reconciliation in the name of science.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Peter McPhee reviews ‘The Revolutionary Temper: Paris, 1748-1789’ by Robert Darnton

- Book 1 Title: The Revolutionary Temper

- Book 1 Subtitle: Paris, 1748-1789

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $65 hb, 547 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Robert Darnton’s magisterial new book investigates the creation of a revolutionary culture in Paris in the forty years before 1789: a ‘temper’ or ‘frame of mind fixed by experience in a manner that is analogous to the “tempering” of steel by a process of heating and cooling’. Parisians became aware of ‘seemingly limitless possibilities’.

Darnton, born in 1939, was for forty years a professor at Princeton University, before being appointed librarian at his alma mater, Harvard University, in 2007-15. An eminent historian of books, as a librarian he was equally innovative in digitisation and ePublishing, his passions expressed in The Case for Books: Past, present, and future (2009). His new book is the creation of a master stylist, a profoundly erudite man whose love of language captivates the reader with its mix of deft touches, humour, and bold assertion.

In a series of path-breaking books across his long career, Darnton has changed the way we understand the Enlightenment and its impact – indeed, the way we understand the relationship between books and their readers in general. He did this by asking and answering a simple but difficult question: what did people want to read in the late-eighteenth century?

Of a time when there were no bestseller lists, and the censors employed by the monarchy and the Church controlled the approval of ‘legal’ books, Darnton discovered a clandestine, illegal book trade based in Switzerland which revealed more about what the reading public wanted. His studies of publishing – an economic as much as a cultural behaviour – were particularly revealing about the cultural changes of the 1770s and 1780s. The popularity of conventional books about theology and law was challenged by books about travel, scandalous court cases, and history. But, while the authorities tolerated the trade in cheap Swiss editions of works ranging from the Encyclopédie to the Bible, it was the underground trade in totally banned books that is most revealing. What would booksellers and their suppliers risk imprisonment to sell in order to meet public demand?

The Swiss catalogues offered readers at every level of urban society a socially explosive mixture of philosophy and obscenity: pirate editions of the finest works of Voltaire, Rousseau, and Holbach jostled with brochures and books with titles such as Venus in the Cloister, or the Nun in the Nightdress. In the land of Rabelais and Molière, there was nothing unusual about sharp sexual satire; what was new, however, was that it was widely circulated and often political, mocking salaciously the sexual peccadillos of the élite of the court and Catholic Church. The subversive tone of these books and pamphlets was paralleled in popular songs laughing at courtly excess.

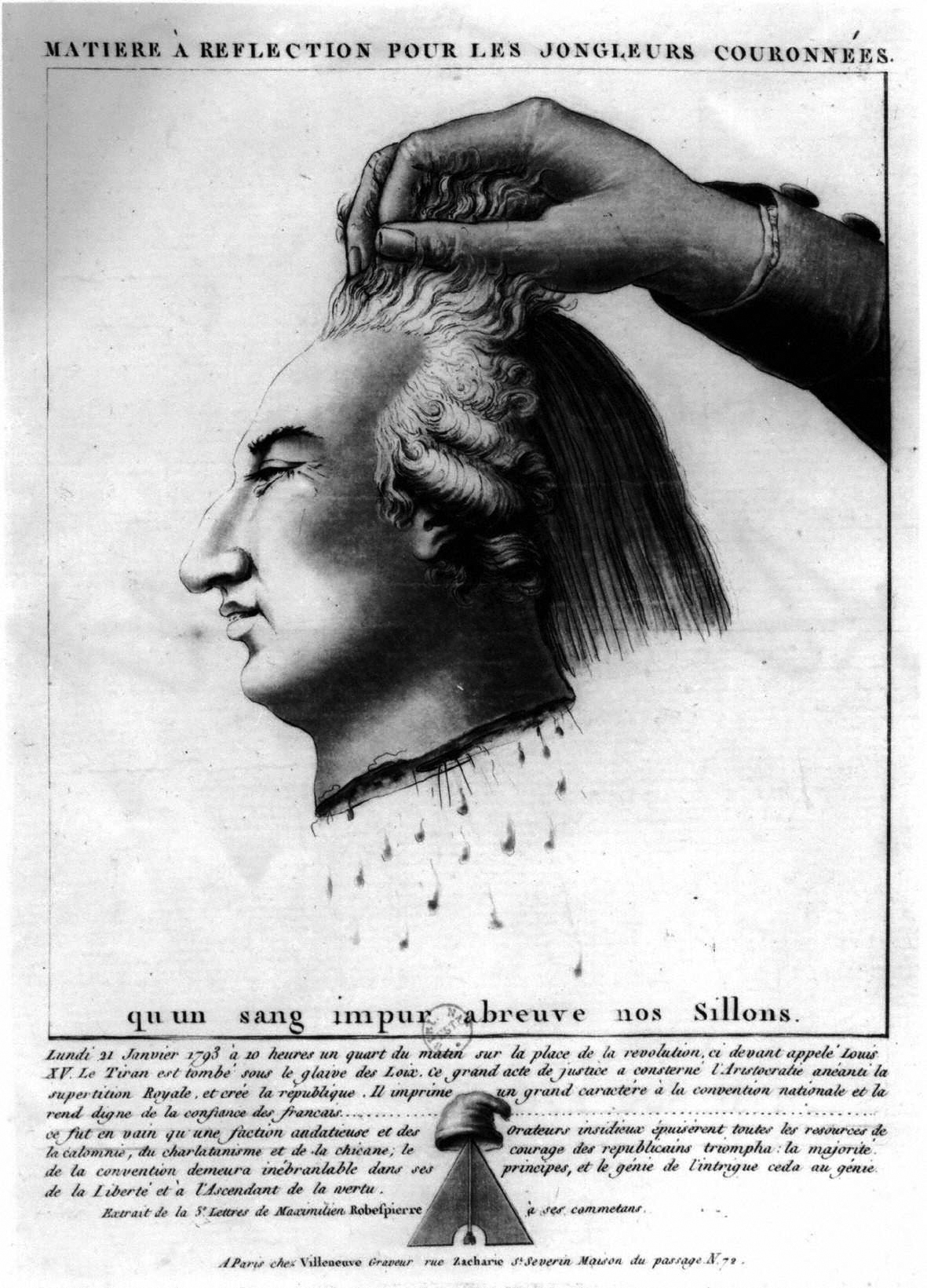

Anonymous engraving – Louis XVI put to death, 21 January 1793 (Photo 12/Alamy Bibliothèque Nationale)

Anonymous engraving – Louis XVI put to death, 21 January 1793 (Photo 12/Alamy Bibliothèque Nationale)

The royal couple was not spared. The 1781 libel Les Amours de Charlot et Toinette began with a description of Marie-Antoinette masturbating and of her affair with her brother-in-law, and it ridiculed the king’s alleged impotence and supposedly tiny genitalia: ‘instead of fucking, he is fucked’. The queen’s profligacy – earrings made for her in 1785 cost 800,000 livres when most Parisian wage-earners earned less than 1,000 yearly – earned her the sobriquet ‘Madame Déficit’.

In his latest book, Darnton enriches his analysis by placing the history of publishing and reading within a wider context. This is an exercise in the ‘cultural construction of reality’ or ‘collective consciousness’, drawing on Weber, Geertz, and others. Darnton’s profound knowledge of the world of ideas, the print media, and politics enables him to evoke in captivating detail the public hunger for innovation and critique. He takes us into the streets and cafés of Paris, a congested cauldron of debate, friction, and sometimes riot. Rumour-mongers gathered daily under the Tree of Cracow – a large chestnut tree in the gardens of the Palais-Royal – to exchange news of the latest scandals.

Side by side with the aristocratic language of birth, privilege, and obligation emerged a civic discourse of ‘virtue’ to indicate civic and moral excellence. Terms such as ‘public opinion’, ‘citizen’, and ‘nation’ became frequent in political discourse. Above all, ‘virtue’ became the watchword for rectitude, exemplified by Swiss patriots, American farmers, and ‘noble savages’, but not by bewigged courtiers.

For Darnton, this revolutionary ‘temper’ sapped support for traditional hierarchies and fuelled a revolution for liberty and equality. It was, above all, a revolution of ideas. Others would argue differently: that it was the expansion of capitalist enterprise in manufacturing, agriculture, and, principally, colonial commerce, which was generating forms of wealth, behaviour, and values discordant with the institutional bases of absolutism and the claims to authority and privilege by the nobility and Church.

However, the greatest gap in Darnton’s analysis is his dismissal of the world outside the walls of Paris: ‘to wander through the provinces would be to lose the narrative thread in an overabundance of detail’. Yet this was a national rather than a Parisian revolution. Commoner deputies elected to an advisory Estates-General in 1789 adopted the revolutionary stance of calling themselves the National Assembly on 17 June, and then took the ‘Tennis Court Oath’ never to disperse three days later. They were provincial, bourgeois men: only twenty of the 578 deputies were representatives of Paris. Deputies from Calais to Perpignan shared a revolutionary outlook.

Rural people made up at least eighty-five per cent of the French population, and this was their revolution, too, despite their total absence from this book. When news reached them of the storming of the Bastille on 14 July, they unleashed the greatest insurrection in French history, the ‘Great Fear’ of July-August 1789, which shattered the feudal system. But Robert Darnton is most at home in the Parisian world of books, plays, and newspapers, to our great benefit.

Comments powered by CComment